The Ottoman Empire, which emerged as a conquering power in Southeastern Europe in the latter half of the fourteenth century, fundamentally altered Hungary’s geopolitical situation. Although the fight against the Ottoman Turks initially became a matter of life and death for the Balkan Slavic states following the defeat of the Crusader army at Nicopolis in 1396, Hungary was also eventually forced onto the defensive. This prompted the Hungarian King Sigismund (r. 1387-1437) to develop a new defensive strategy. His plan rested on three main pillars. On the one hand, he sought to establish a buffer zone along the border between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, and on the other hand, he consolidated the existing system of military districts, or banates, located along the southern border and which was connected to the developing system of border fortifications.

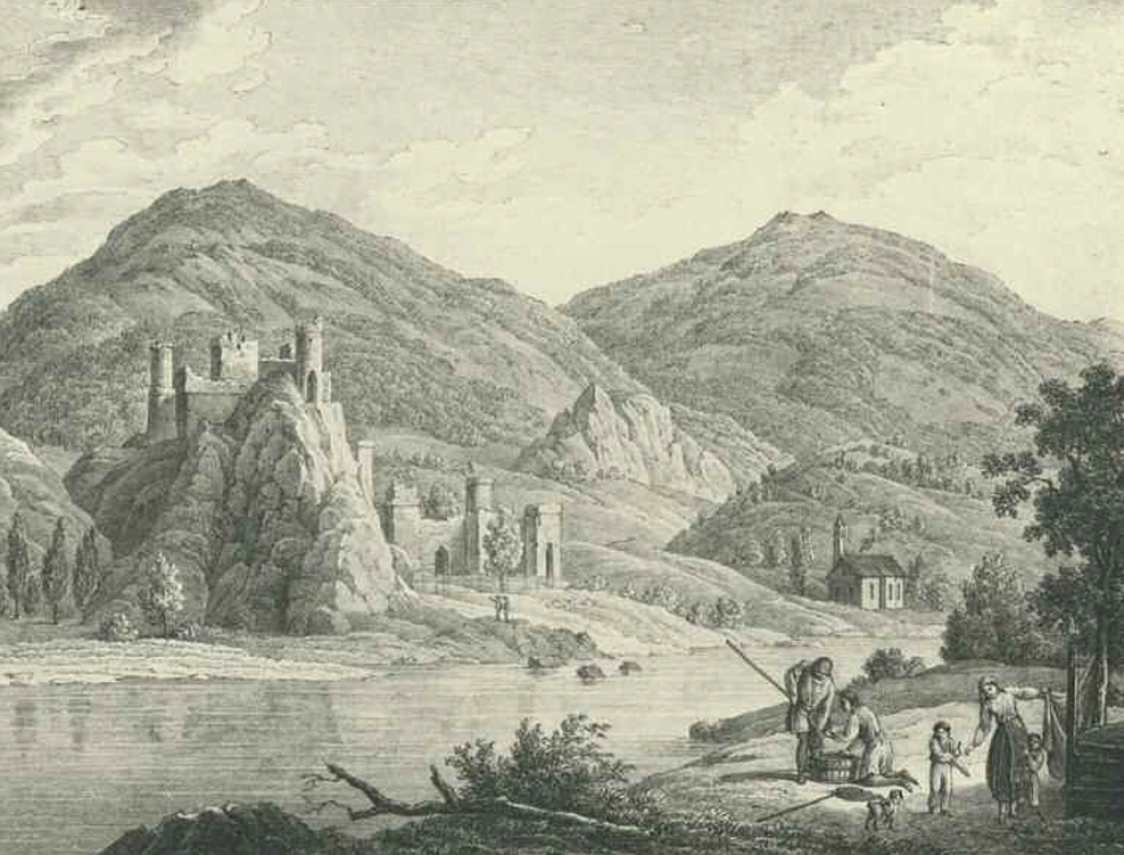

Galambóc (Golubac) Fortress following its reconstruction in the 2010s. The fortress, with its high walls, was one of the strongest forts along the southern frontier in the fifteenth century.

The buffer zone

When King Sigismund set out to strengthen Hungary’s defenses, he sought to create a buffer zone of vassal states arrayed along the southern frontier. The intention was to repel Turkish attacks in Bosnia, Serbia, and Wallachia before they could reach Hungary. In order to ensure that these states become Hungarian allies, Sigismund tried to bind their rulers to him by offering land titles in Hungary. The most important of these intended buffer states was Serbia, ruled by the despot Stefan Lazarević.

The Serbian ruler was a vassal of the Ottomans until the latter’s defeat at the Battle of Ankara in 1402 but subsequently switched his allegiance to Sigismund. In return, Lazarević was soon gifted the fortress of Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) and the Banat of Macsó, was granted lands in Hungary, and was inducted into Sigismund’s Order of the Dragon. Lazarević remained loyal to Sigismund until his death in 1427, and Sigismund subsequently recognized György Brankovics as the despot’s successor, in accordance with the Treaty of Tata, signed the previous year. However, Hungary’s relations with Serbia under its new ruler were no longer as straightforward as they had been under Lazarević.

A more panoramic view of Galambóc Fortress, showing its dominant position over the Danube.

Sigismund’s policies were less successful in Bosnia, where political conditions were more unstable. Due to the prevalence of the Bogomil heresy, which rejected both Catholicism and Orthodoxy, and the internal crisis following King Tvrtko’s death in 1391, the Hungarian king often needed to intervene militarily in order to assert his power.

The situation in Wallachia was no less complicated than in Bosnia. Mircea the Elder, who was loyal to the Hungarian king, ruled the principality as voivode until 1394, when he was expelled by Vlad I. In 1402, the exiled voivode regained his throne and remained Sigismund’s vassal until his death in 1418. Mircea’s son, Michael I, became the new voivode in 1418, followed by Radu II in 1420 and Dan II in 1422. Hungary continued to support this succession of voivodes against the Turks. The situation took a turn for the worse in 1432, when Sultan Murad II was able to make Dan II’s successor – Alexander I Aldea – his vassal. In 1436, a Hungarian expedition helped install Vlad II Dracul as voivode; nevertheless, Dracul’s reign saw the principality come under permanent Ottoman-Turkish influence.

Thus, by the end of the 1420s, Sigismund’s buffer state plan had effectively reached a dead end. As a result, the system of fortresses along the southern border, under construction since the end of the fourteenth century, became increasingly important.

The topography of the southern border region

The southern border of the medieval Hungarian kingdom stretched from the high and virtually impenetrable mountains of the Southern Carpathians, along the course of the Danube and Sava rivers, through the Dinaric Alps, all the way to the Adriatic Sea. The central and western parts of this long border region were the most exposed to attacks by the Ottoman Empire. Of the roughly 900-kilometer stretch between Szörényvár (Drobeta-Turnu Severin) – at the southern terminus of the Carpathians – and the sea, it was the section between Szörényvár and Nándorfehérvár that was most subject to Turkish incursions.

Croatia and Slavonia, bisected by the Dinaric Alps, lay in the western part of the southern border region. In the Middle Ages, Hungary’s territory extended as far south as the northern and northwestern parts of Bosnia. The Dinaric Alps define the topography of Bosnia, which is divided by several river valleys easily accessible to military forces. The most significant of these are the Vrbas, the Drina, and the Bosna, which flow into the Sava.

The most important sector of the southern border zone was the region of Szerémség (Syrmia), Bácska, Bánát, and Temesköz – between the Danube and the southern reaches of the Carpathians – as this was the locus of most Ottoman attacks from the fourteenth century onward. This southern border region boasted some of the richest and most fertile lands of medieval Hungary. Szerémség was bordered to the north by the Danube River, from the Drava River in the west to the confluence with the Sava to the east, with the latter river forming its southern boundary. In the west it was bounded by the swampy lowlands around Eszék (Osijek), which is why Szerémség was often referred to as an island. In the Middle Ages, this region was considered an integral part of Hungary, comprising the counties of Pozsega, Szerém, and Valkó. The northern part of the region is marked by a tableland – the Tarcal (Fruška Gora) – which rises above the neighboring plain. This tableland extends for approximately 90 km, stretching eastward from Valkóvár (Vukovar) in the west, along the southern bank of the Danube, to the area around Újlak (Ilok) in the east, where its slopes become more gentle. The Tarcal was home of medieval Hungary’s most famous wine region, which produced Syrmian (szerémi) wine. Apart from this tableland, the region comprises a plain dotted with swamps and small rivers.

The Bácska, Bánát, and Temesköz regions lie at an altitude of 100-200 meters above sea level and are among the most fertile regions of the Great Hungarian Plain. To the south flows the Danube River. Swampy and boggy patches comprised the only internal barriers. Flooding of the Tisza River and its tributaries submerged vast areas of this region in the Middle Ages, resulting in a significant amount of wetlands and areas periodically covered by water. This southern border region situated along the Danube becomes gradually more mountainous the further east one goes. A succession of rugged and forested ridges – the Loka, Almás, Orsovai, and Semenik Mountains – begins at the Néra River and ranges between 1200 and 1500 meters in height. The defensibility of this border section was enhanced by the fact that the lower Danube flows through increasingly steep precipices, starting from Babakáj Rock, which juts from the river at Galambóc, and posed a danger for ships between Drankó and and the Iron Gate (Vaskapu).

From a geostrategic perspective, the Hungarian border, anchored on the Danube and Sava rivers, mostly favored the defenders, offering excellent protection for more than a century. This was largely due to the fact that Hungary was able to retain its hold on Nándorfehérvár, at the confluence of the Sava and the Danube rivers, while also maintaining possession of the strategic Jajca and Szrebernik fortresses in Bosnia.

The frontier fortification system and the banates

The defense system built during the reign of King Sigismund – which took the natural topography into account – was organized in the following manner. In 1399, the king brought together a number of southern counties, namely, Temes, Csanád, Csongrád, Arad, Krassó, Keve, and Zarand, as well as the Vlach territories, and placed them under the control of the lord-lieutenant (ispán) of Temes County. As a result, the entire area between the Maros – from the Béga and Temes rivers to the Tisza – and the Danube, one of the most important sectors of the defense, was placed under unified control. Starting in 1404, command over the Temes Banate was conferred on Pipo Spanno (Ozorai) before passing into the hands of the Talovac (Tallóci) family.

The Macsó Banate, established during the reign of King Béla IV (r.1235-1270), played a particularly important role in defending the central and eastern parts of the southern frontier. This banate was under the suzerainty of the Serbian despot from 1402 to 1427 before devolving back to Hungary. The Croatian and Slovenian banates also played an important role in the fifteenth century, creating a defensive hinterland behind the Jajca and Szrebernik banates in order to secure the frontier fortifications if attacked.

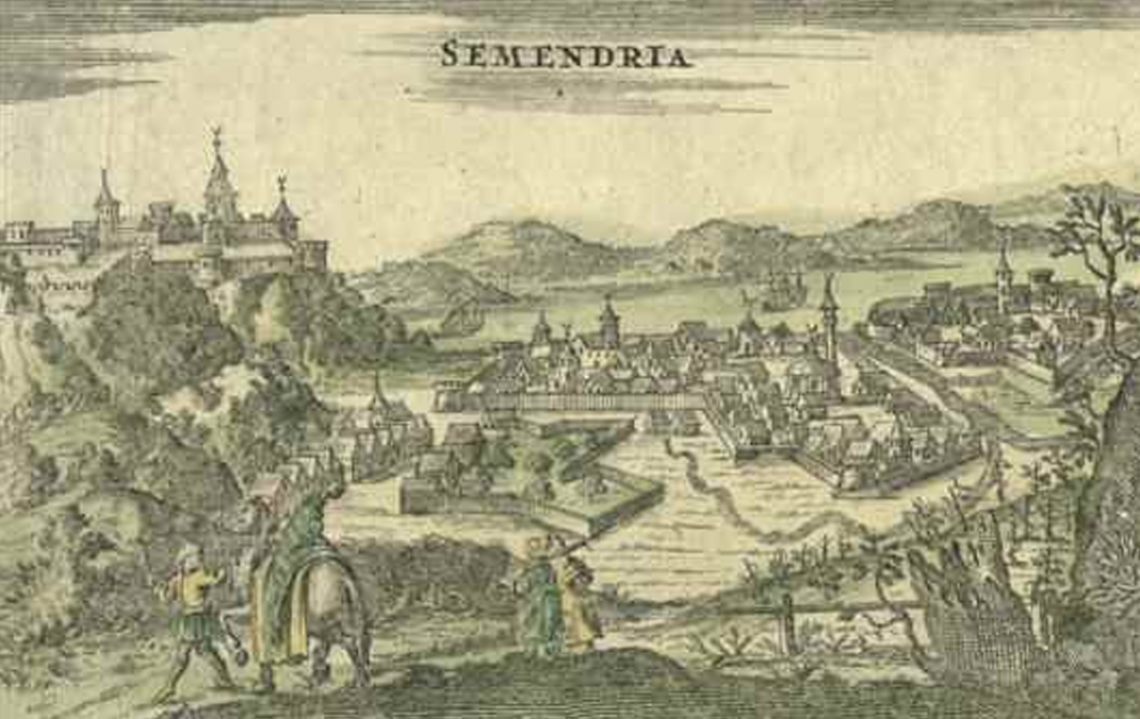

The inner city walls of Szendrő (Semendria) Castle, built in the fifteenth century by the Serbian despot György Brankovics. This vast fortress resisted the attacks of Sultan Mehmed II’s army in 1456 but fell to the Ottomans in 1459 and remained under Turkish rule for centuries.

The border fortresses and castles, located along the frontier, formed the first line of defense. In 1419, Sigismund annexed Szörényvár to Hungary in order to strengthen the frontier defenses and incorporated the surrounding Szörény Banate into the southern defense system. From the outset, the king took control of the fortresses along the lower Danube, strengthened them considerably, and built new ones. Previously, only the fortresses of Görgény, Orsova, Galambóc, Haram, and Keve stood between Nándorfehérvár and Szörényvár, along the southern boundary of the Temes Banate. The ban of Temes, Pipo Spanno, played a significant role in the construction of the new fortresses. Whereas the fortress of Dombó (Dubovac) may have already existed at the end of the fourteenth century, Spanno rebuilt those at Orsova and Szörényvár in 1424. By around 1430, some 11 new fortresses stood in this threatened sector. Sigismund had the fortress of Szentlászlóvár built at the entrance to the Iron Gate – opposite Galambóc in Serbia, where the Turks had established a garrison in 1427. As a result of these initiatives, the following major fortresses now occupied the Nándorfehérvár–Szörényvár sector in the fifteenth century: Orsova, Miháld, Pét, Szinice, Drankó, Szentlászlóvár, Pozsazsin, Haram, Dombó, Keve, and Tornyistye. Hungary did not see fortress construction of similar magnitude until the fall of Buda in 1541.

One of Sigismund’s most important decisions was to bring the fortress of Nándorfehérvár back under Hungarian rule in 1427, in accordance with the Treaty of Tata of 1426. The fortress, which was expanded into a significant stronghold during the reign of the despot Lazarević, was considered the gateway to the Kingdom of Hungary and played an enormous role in defending the country’s southern frontier. Its possession was also important as it served as a springboard for Hungarian campaigns in the Balkans. In other words, as long as Hungary possessed the fortress of Nándorfehérvár, the Sultan could not complete the conquest of the Balkan Slavic states.

The year 1427 also saw the return of other important southern fortresses – Szokol, Brodar, Dragisa, Halap, Macsó, etc. Meanwhile, the same year saw Galambóc’s Serbian captain surrender the fortress to the Ottomans, citing a debt. In 1428, King Sigismund laid siege to the fortress on the banks of the Danube, but the military expedition failed.

To defray the costs of maintaining this defensive system, the king entrusted the lower Danube frontier to the Teutonic Order between 1429 and 1432. It should be noted that Sigismund had already offered to entrust the Order with the protection of the entire southern frontier following the defeat of the Crusader army at Nicopolis, but this had been rejected by the Grand Master Konrad von Juningen and his advisors. An agreement was eventually reached, but it proved short-lived. This may have been due to the fact that the Ottomans had inflicted a harsh blow on the German crusaders, as the historian Eberhard Windecke noted:

“In the aforementioned year [1433], Emperor Sigismund received news that left him dejected. This was nothing other than a report that the Teutonic Order had suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Turks. The fact that the German crusaders had suffered such a great loss was also due to the voivode of Wallachia, the son of Mircea [the Elder], whom the emperor had elevated to the rank of nobility in Nuremburg [seat of the imperial diets]… and had granted the principality of Wallachia, sided with the Turks against the Crusaders. The Turks had also been supported by the Polish king [who was in the midst of his own conflict with the Teutonic Order], along with the Czechs, with the Czech heretics [the Hussites] joining forces and attempting a march through Hungary. When the Holy Roman Emperor complained about all this to the Council of Basel, he asked them to put an end to the conflict, since the Turks, Hussites, and Poles were mutually supporting each other and the heretics were growing in number.”

Since the arrangement with the Teutonic Order did not pan out, Sigismund attempted to rationalize the southern frontier and entrusted the entire defense to the Talovac family, a decision that was in accordance with Sigismund’s previous acquisition of the fortresses along the lower Danube and the joint command of the Banate of Temes. Several important positions were thereupon assigned to the House of Talovac. In 1429, Matko Talovac was appointed captain of Nándorfehérvár, while his brothers held the banates of Croatia, Slavonia, and Szörény, the Archbishopric of Kalocsa, the bishoprics of Csanád, Várad, and Zagreb, the Prefecture of Vrána, and numerous counties. They held sway over some 52 fortresses along the southern frontier, which also included the salt chamber of Temesvár–Keve and the collection of salt duties in the areas under their control.

In Hungary, such a concentration of power alongside the central authorities was rare. By doing so, Sigismund granted the Talovac brothers economic and military resources sufficient to maintain the defensive system entrusted to them. The aim was to ensure that the hinterland beyond the border fortifications – the banates and the military forces stationed therein – could provide effective support for the fortresses. The fortifications built under Sigismund worked quite well, as evidenced by the siege of Nándorfehérvár in 1440, when Sultan Murad II made a failed attempt to capture the city. King Ulászló (Vladislaus) I would later concentrate so much power in the hands of János Hunyadi and Miklós Újlaki that they were able to strike out independently in dealing with Turkish incursions in the areas entrusted to their care.

King Sigismund proceeded similarly in other parts of the southern border. He reinforced the crossings along the Sava with wooden fortifications and stationed Hungarian guards in Bosnian fortifications. Jajca and Szrebernik came under Hungarian rule, and Hungarian garrisons were also stationed in the fortresses of Bobovác, Dubočac, Vranduk, and Toričan. There were also fortifications along the Adriatic coast as well, but both during the reign of Sigismund and in the first half of the fifteenth century, it was mainly the section between Nándorfehérvár and Szörényvár that was exposed to Turkish attacks.

Military forces supporting the border fortresses

The fourth element of the Hungarian defenses along the southern frontier – after the buffer zone, the banates, and the fortifications proper – was the field army, which could come to the relief of the border fortresses when required. In order to defend against the Turks, the number of lightly armed troops had to be increased so that the Hungarian military could engage in similar tactics as those used by the enemy. The Diet of Temesvár, convened in 1397 in the wake of the defeat at Nicopolis, was summoned in order to achieve these goals. Wealthier nobles were actually required to raise a “mercenary army,” with one mounted archer to be provided for every twenty serfs. Moreover, Sigismund insisted that in view of the Turkish threat, the nobles had to remain loyal even if the king were to lead an attack against the Ottomans abroad.

In 1433, Sigismund drafted a reform proposal according to which certain high ecclesiastics, large landowners, and counties were obligated to raise military forces against the Turks according to the following schema:

1. The king, the Croatian ban, and the counts of Korbavia, Cetinje, and Segni were to send 3000 horsemen to the Adriatic and Dalmatia to fight against the Turks and their allies.

2. The ban of Slavonia, the abbot of Vrana, the bishop of Zagreb, Lőrinc Tahi (Tóth), and the lords of Blagay were to send 2500 horsemen (500 each) to fight against the Turks on the Una River.

3. Some 16,900 horsemen were to be deployed against the Turks in the Ozora (Usora) region in Bosnia. Of these, the Serbian despot was to provide 8000, Bulgaria 4000, and the rest provided by the lord lieutenant of Pozsega, the bishops of Bosnia and Pécs, the lords of Bothos, the ban of Macsó, János Garai, Péter Cseh Lévai, János Gergelyffy, János Maróthi, Matkó Tallóci (Talovac), Henrik Wajdafy, and György Lóránd Herkei.

4. The archbishop of Kalocsa, the bishops of Várad and Csánád, the king, the Wallachians, the Cumans, and the Jász people, as well as the counties of Temes, Keve, Zaránd, Arad, Csanád, Torontál, Krassó, and Csongrád, were to provide 3800 horsemen for the Temesköz region extending as far west as Szörény.

5. The nobles of Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slavonia, the remaining parts of Bosnia, the Duchy of Saint Sava (Herzegovina), and the counties of Verőce, Somogy, Zala, Baranya, Bács, Pozsega, Valkó, Bodrog, Szerém, and Tolna were to arm 12,500 horsemen in total.

6. In Transylvania, the king, the bishop of Transylvania, the voivodes of Wallachia and Moldavia, the voivode of Transylvania, the Székelys, the Saxons, the Transylvanian nobles, and the counties of Bihar, Békés, Szatmár, Szabolcs, Ugocsa, Máramaros, Bereg, Kraszna, and Outer and Inner Szolnok were to provide a total of 21,150 horsemen against the Turks or any other enemy, if required.

Sigismund intended this system to resolve Hungary’s defensive issues against the Ottoman Empire. If all the soldiers enumerated in his list were gathered together, some 60,200 horsemen could have been fielded against the Turks. The draft plan shows that the king was counting not only on the forces raised by Hungarian high ecclesiastics, lords, and counties but also on those amassed by Hungary’s southern neighbors, which were intended to serve as a buffer zone. Sigismund’s plan, however, was never realized, even though it was enshrined in law in 1435.

***

Later events would show that the defense system Sigismund constructed along the southern frontier worked well. This was evidenced by the sieges of Nándorfehérvár in 1440 and 1456 but also by the fact that the loss of Szendrő in 1439 did not lead to any serious repercussions. The defense system required no significant changes until 1471, already during the reign of King Matthias. Historical events ultimately proved King Sigismund’s defensive concept as correct, as the frontier fortress system resisted Ottoman incursions until 1521 and protected the Kingdom of Hungary from foreign conquest.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)