It would be no exaggeration to say that the last few decades have seen a striking shift take place in the social sciences – one that could be called nothing less than revolutionary. Cult research, as it is called, has revealed that an invisible but extremely powerful lens sits perched on the noses of those retrospectively analzying tradition. In literature, the arts, and often even politics, we have looked upon – and continue to look upon – a great many historical figures with a kind of peculiar, unconscious naivety, through the exclusive lens of the idolatry that surrounds them.

Mythical timelessness

The above is particularly true in the case of Hungary’s much beloved poet, Sándor Petőfi. Researchers have demonstrated that children in kindergarten, and even more so in elementary school, are already well-acquainted with the name and character of this unique and exceptional poet and revolutionary, along with the respect to which he is entitled, long before encountering his poetry and the moral example which his life offers.

And why is this a problem? – some may ask. Can a cult not reveal the truth? Indeed, it can, but the order should be reversed. It is misguided to let the heroic and tragic details of the poet overshadow his words and lines. A writer’s rightful place in our intellectual life should be determined through familiarity with and appreciation of their poems and texts.

Everyone knows Petőfi as “the poet,” but when his poetry is mentioned, it is rather his biographical details and, mainly, the different roles he played which first spring to mind. Rarely do we consider what made his good poems truly good or what it was that made the possibly bad ones poor. The creator, the illustrious wordsmith, the weaver of wondrous meandering stories, the subject of lyrical confessions, lies hidden behind these heroic masks. And yet he is there, merely waiting to be unveiled. It is no coincidence that one of the twentieth century’s great Hungarian writers, the exiled Sándor Márai, when fearing the degradation of his mother tongue from exposure to foreign languages, read Vörösmarty, Arany, and Petőfi every morning – all three of them! This is how he maintained his linguistic spontaneity and familiarity.

“The most sacred duty of the society is to lead the faithful in singing the praises of the Petőfi cult,” declared Gyula Kéry, secretary of the Petőfi Society, on the occasion of the ceremonial opening of the Petőfi House in Pest in 1911. “I should also mention that I have always held deep respect for the highly esteemed members of the clergy. It is they who sow humanity’s greatest treasure in the human soul – faith. I consider them kindred spirits because the members of the Petőfi Society are likewise […] priests of a beautiful and noble vocation. You are the apostles of faith; we are the apostles of the Petőfi cult […].”

Elsewhere he noted that “the Petőfi House has been most visited on Tuesdays, when admission is free. The audience then is the most interesting: the proletariat. […] And they all walk with their hats doffed and on tiptoe, as if in church. One time a working woman entered the main hall, sought out the holy font, and blessed herself with the sign of the cross.”

Clinging to his mother tongue, the exiled Márai communed with Petőfi, the true master of the Hungarian language, every morning. But this is a rarity in Petőfi’s posterity because everything has been eclipsed by the magical power of his cult. Ever since the Compromise of 1867, every regime has sought to exploit and appropriate the poet as a symbolic figure for its own official political, cultural, and ideological ambitions or manipulations with the corresponding opposition – the intellectual and moral opponents of these regimes – acting in a similar manner.

Petőfi’s renown rested on a century and a half of school lessons that placed him at their center, on the annual public celebrations of his life, and on institutions bearing his name − so much so that even Hungarians who do not recall his poems immediately associate his name with poetry.

István Margócsy, literary historian and one of today’s most foremost Petőfi scholars, illustrates this extraordinary effect with an example: “Among the slogans of the 1956 Petőfi Circle (what else could they have called themselves) and their concrete political demands the following suddenly appeared: “Long Live Petőfi’s Youth!” What did this actually mean? Even if hard-pressed to explain the significance of this revolutionary demand, we would nevertheless feel it has a place among revolutionary slogans.

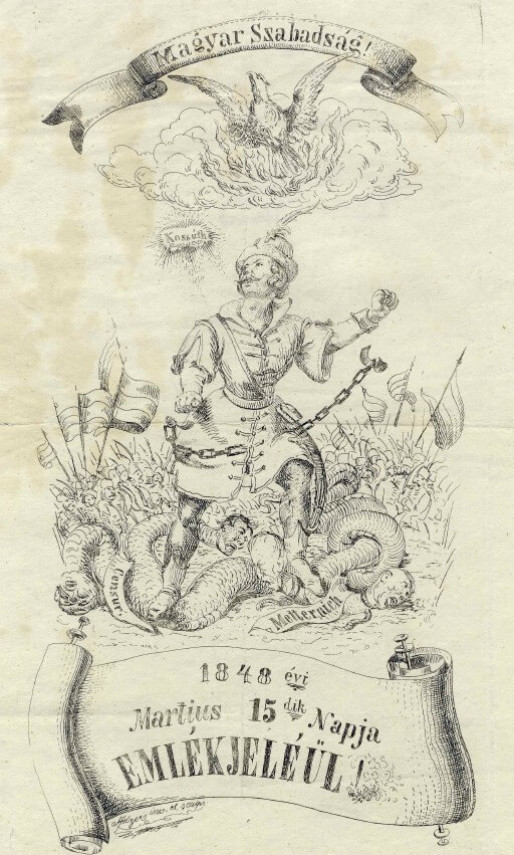

Petőfi, however, was not just a poet. He was also an important figure in the world of politics. Some of his deeds are retained in the collective memory to be amongst the most important moments in Hungarian national life. There are two reasons for this. On the one hand, he played a part in the great founding narrative of the modern Hungarian nation: the myth and reality of the 1848-49 Revolution and the War of Independence. Thus, he has become a sort of “timeless” figure, like other mythical heroes for whom there is neither a beginning nor an end; they simply “are” and “exist” eternally. And this mythical timelessness offers space for the imagination to continue weaving stories about its favorite hero.

What the politician proclaimed

Although historical events played a major role in the development of the cult, Petőfi’s own personality was a contributory factor. By placing talent and achievement – rather than origins – at the center of its humanist values, nineteenth-century humanism endowed great artists with a kind of adoration comparable to modern celebrity culture. As we saw earlier with the visitors to the Petőfi memorabilia exhibition, many aspects of such adoration are clearly inherited from religious practice. It was under such circumstances that Petőfi acquired great popularity, first among a small circle of admirers and then later in an ever-expanding cultural and intellectual space. Gergely Pünkösti, a Hungarian officer and major in the 1848-49 Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence, cites the memorable example of the then-Captain Petőfi, who was travelling by cart to join General Bem’s army in January 1849. He had just left Medgyes (Mediaș) when some soldiers approached him on the road. It was as if he was reciting from his own epic poem:

Magnificent hussars approached him, astride

Magnificent steeds, shining swords by their sides;

Each proud charger was shaking its delicate mane

And stamping and neighing in noble disdain.

(translated by John Ridland)

They were a troop of Szekler reinforcements from Transylvania, and when their commander asked him who he was, news spread among the ranks as his name was announced and a thunderous cheer erupted!

And what was the reason for this soldierly salutation? Was it for the poet’s magical words, or, were they perhaps, cheering for the politician – the resolute champion of human rights and advocate for the economic demands of the peasant masses? We may get closer to an answer, and with this, a better understanding of Petőfi’s political stance – which crops up in his poetry – by comparing his statements with the views of the liberal reform opposition leader of the time, Lajos Kossuth.

In addition to overthrowing specific social, national, and political oppression, the poet’s significant statements prove that he sought to eliminate all forms of tyranny and despotism. He viewed the revolution as a means to this end and as something he regarded as the idealized pinnacle of social action. He believed that the “ultimate” goal of the revolution was to achieve nothing less than the fulfillment of happiness based on the equality of peoples, nations, and individuals. Petőfi was not a political-legal theorist; he did not write about political theory. Rather, he created a utopian vision. Amongst the 19th century poets, he professed that only when “the horn of plenty,” “the table of justice,” and “the spiritual light” become available to all, would the biblical new “Canaan” come to pass for all peoples.

What is the most important instrument for achieving this goal? The attainment of “liberty,” or rather, self-determination; when one has a voice in the shaping of one’s own destiny, one is free. As a democrat, he added that only by leading “the people through fire and flood” – together with him – could freedom be achieved. This vision, no doubt, inspires, but it is not a concrete plan to deal with everyday political struggles. He does not speak of regulatory prerequisites, necessary and commensurate tactics, contextual evaluations of any given time, or the “right there, right then” contingencies. Along with other 19th century poets he purports that “[until we reach our goal]we must continuously struggle.” But he also adds that “perhaps our life’s work will not pay anything back”, and what is more, there will be many heroes for whom the struggle for “a free world” will end in “a common grave.” Thus, the forging of a common happiness is the goal, which can only be achieved when the people win their final victory over tyranny through revolutionary struggle.

How did Kossuth perceive these ideas?

Like all thinkers who respected the legacies of Christianity and the Enlightenment, Kossuth embraced the pursuit of “common happiness”; yet his goal was more specific: to achieve a successful civil transformation that would secure self-determination for a united society as one nation. Both Kossuth and Petőfi, as proud and self-aware intellectuals, defied the world of the privileged, as both, until 1848, earned their living with their pens − and could not, in a political sense, be bought. Both desired to dismantle the existing social and political order, but their distinct positions were influenced by the social background from which they hailed and consequently, from where they entered the world of public political debate.

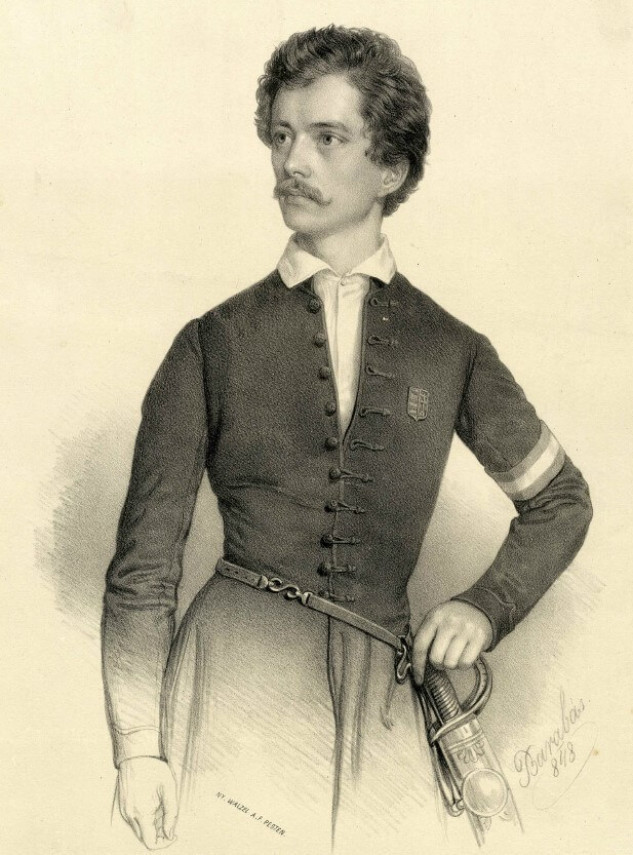

Júlia Szendrei. Based on a painting by Miklós Barabás Lithograph by A. Walzel, Ny.

Petőfi was from a conventional unexceptional market town composed primarily of lower middle-class citizens, and so, with the maximum determination and integrity characteristic of those who find themselves outside the “system,” he could identify with the ideology and radicalism of the former French revolutionaries. Kossuth, on the other hand, was from the nobility, an intellectual who sought to bring internal inconsistencies to a head by harnessing the pressure of external forces, namely, the peasant population and citizens. He wanted to rally the best of the nobility from the ruling classes and, in the spirit of united interests, put them at the forefront of the external forces pushing for change. Categorically opposed to any revolutionary violence, he sought to restrain the frustration and restlessness of the underprivileged, taking into account the relative weakness of their forces as well as recognizing the enormous economic, social and political clout brandished by the nobility of the country.

He recognized that if the underprivileged entered the struggle independently, the privileged would set aside their internal conflicts and reinforce the feudal hierarchy subordinated to Habsburg rule. This had to be avoided at all cost. Kossuth sought for a compromise, thus encouraging the radicals who were relentlessly attacking the “old order” to accede to the political leadership of the reform opposition led by the nobility. This gave rise, understandably, to much bitterness among the radicals. Petőfi shared their view, and formulated his criticisms countering it. Meanwhile, Kossuth incurred the antipathy of the supporters of the “old order” and those who sought to modernize the system of hereditary privileges.

Although Kossuth, along with many of his distinguished colleagues, applied external pressure as a means of successfully undermining the internal defenses of the feudal world, he did not, even in 1847, share Petőfi’s unequivocal conviction for a revolution. Rather, he continued to support reform activities and emphasized the necessity of slow and hard work to counter the “centuries-old bigotries”:

“It is our thankless, but not futile, task to endeavor to exhaust all possibilities. It is not futile because it either helps to achieve our goal or serves as a reminder of our struggles – a well-trodden path for those who follow in our footsteps and, with renewed vigor, undertake the work where we will have left off. A tree cultivated from centuries of bigotry cannot be felled by a single strike. But let us chip away; with every cut we weaken their bole and edge nearer to a final decisive blow. Let us chip away!”

At the same time he did not completely rule out the option of a revolution either, but only, as his famous, oft-quoted words attest, as a last requisite resort:

“Be not so afraid of anarchy that, out of excessive fear, you dread liberty as well. Let us consider, if we were to be so despondent that we could only choose between anarchy and absolutism (which I do not believe), anarchy could only ever be a temporary state, whereas tyranny could be eternal. If there were to be no other way, let us trample across temporary aberrations toward the stability of freedom rather than find ourselves in the dead silent and orderly bondage of despotism.”

This was the maximum extent to which Kossuth went in terms of overtly endorsing the revolution before 1848, one that cleared an opportunity to meet with, though not identify with, Petőfi. The fact that they finally did meet in the spring of 1848 was enough to bring about an epic feat that changed the course of history.

The politician in action

Petőfi, therefore, did not devise a plan that could have translated utopian visions of popular liberty into a concrete political action program to be carried out in daily practice. However, their ultimately opposing viewpoints did not prevent them from cooperating in order to overcome the obstacles looming directly before them. A striking example of this was their joint appearance on March 15, 1847, at the opposition conference − exactly one year before the decisive March 15 of 1848 . Whereas, Kossuth apprised his fellow like-minded colleagues about the basic principles of the unified opposition program, Petőfi reaped prodigious poetic success with the recitation of his poem: “In the Name of the People”[ A nép nevében].

György Szabad, renowned researcher of Kossuth’s life and work, drew attention to how Petőfi’s poem not only resurrected and brought back into public consciousness the memory of the peasant leader and martyr, Dózsa György − but profoundly resonated with the ideas of Kossuth’s contemporaries which included Miklós Wesselényi, József Eötvös, and Mihály Táncsics. In Kossuth’s 1846 Hetilap [Weekly News] articles, we can read passages like this:

“Shall I dip my pen in scalding ink to faithfully illustrate the invidiousness which is the inexhaustable source of feudalism?”

Apart from his reflections on the intolerable conditions, Kossuth warned that no one should believe that “we can save the country with raggle-taggle patchwork reforms.” The most important task was to abolish the feudal-serf configuration (his words virtually foreshadowing Petőfi’s formulations) to “grant the people justice, long-denied sacred justice,” without delay. All this, of course, did not achieve the incredibly dramatic and conceptually profound appeal of Petőfi’s words: “The people [still] plead, bestow [it] upon them!,” nor was it his aim. Needless to say, the similarity in underlying content was more than conspicuous. There are also similarities in the imagery used to depict the unfolding of circumstances. It was Kossuth who laid the foundation for the future inception of the nation in which he wished for “the people [to] become one body”, whereas Petőfi spoke of the need for a “pillar of defense” lest the “homeland fall”.

Examining the circumstances around the composition of Petőfi’s “In the Name of the People” [A nép nevében], György Szabad contests that we can discover much more than the mere convergence of content. Quotes from Kossuth’s articles also found their way into István Széchenyi’s admonishing list of criticisms in his work Fragments of a Political Program [Politikai programm töredékek, 1847]. The new pamphlet, within which Kossuth was accused of inciting peasant rebellion was first made available to the reading public in early March, 1847. It was during this time that Petőfi had written, and days later recited, “In the Name of the People” at the opposition conference; echoing and radicalizing Kossuth’s exhortations in the elevated form of poetry. It would be no exaggeration to recognize that, due to the timing of its composition and publication, Petőfi’s great poem served as a gesture of the best traditions of solidarity; fulfilling a political opposition function. Indeed, the poet swiftly came to the aid of his assailed comrade-in-arms, and the principles he upheld, by repeating the very priciples that were the subject of the accusation.

By the spring of 1848, circumstances placed Petőfi, now the leading figure of the Young Hungary literary circle and political circle of friends, in a position where making the right decision demanded genuine political instinct. It is common knowledge that Kossuth, in response to hearing of the 1848 February revolution in Paris, submitted a motion to the lower house of the Pozsony Diet on March 3rd. The motion concerned a letter addressed to the monarch outlining the basic requirements for civil transformation and genuine self-determination in Hungary, and even included similar demands for Austria’s transformation. His speech, which was immediately translated into German, contributed to the impending revolution in the imperial capital. Since the aristocracy was not yet inclined to accept his written proposal, Kossuth and his colleagues turned to the Pest Opposition Circle to launch a nation-wide petition so as to exert pressure.

Led by Petőfi, the young intellectuals from the radical opposition undertook the task of organizing the campaign. They called a public meeting for March 19th at which they intended to adopt, radicalize, and transform into slogans the 12 points that summarized the demands of the reformist opposition. However, when the revolution in Vienna swept away Prince Metternich’s decaying regime on March 13th, the youth, upon hearing news of the event, were faced with a dramatic decision.

What do we read of this dilemma in Petőfi’s memoirs which was written shortly afterwards?

“On March 14, the opposition held a meeting in Pest which, as usual, according to ancient custom, dispersed without result. At this meeting it was proposed that the 12 points should be submitted to the king as a petition, and that without delay. But the then-prevalent spirit of the county judges wanted to carry the matter from Pontius to Pilate, which means that it might not have been resolved before the twentieth century. After all, it was for the best that it happened so… what misery to be asking, when the times themselves command us to demand − not to stand before the throne with a piece of paper, but with a sword! For princes never give of their own free will; whatever we desire from them, we must take!

That evening, Jókai announced the result, or rather, the lack thereof, with great bitterness and utter dejection. Upon hearing this, I too became bitterly disappointed, but did not despair.

I spent most of the night awake, together with my wife; my brave, inspiring, beloved little wife who always encourages my thoughts, and stands before me like a banner raised high afore an army. We deliberated on what to do. Because clearly that which stood in front of us had to be done, and done tomorrow...in case the day after tomorrow would be too late! Logically, the first step and, at the same time, the principle duty of a revolution is freedom of the press...and that we shall do! The rest I trust in God and those destined to continue what they have started; I have been called upon to give only the first push. Tomorrow we shall spar for the freedom of the press! And if they should shoot us down? God bless them, who could desire a more beautiful death?”

Who knows? Perhaps Petőfi’s talent as an actor, his instinct to become the “voice of the people,” and his deep awareness of the bond between himself and his readers all played a role in inspiring this great decision. Whatever the case, the following day, March 15, 1848, saw an exceptional unity of form and substance in a “performance” executed with flawless revolutionary artistry. The timing, the pacing, the spontaneously directed public action, all carried out with acuity, revealed both his poetic imagination and his undeniable political gift.

Wielding a lasting influence…

It is well known, however, that with regard to the transformation, Kossuth and the reformist opposition leaders in Pozsony (Bratislava) perceived Pest’s role in the events of March 15 quite differently. A year later, in March 1849, as he was preparing to visit the Hungarian army stationed at Törökszentmiklós before their confrontation with the imperial troops during the Spring Campaign, Kossuth, then Head of the National Defense Committee, wrote the following lines to his wife: “Today you celebrate March 15, while our troops prepare to face the Germans. What is there to celebrate on March 15, when all that happened was a little commotion in Pest? But this I do know: on the day the army saves the homeland, there will truly be something to celebrate.”

Of course this is not just exaggerated hindsight. Young historian, Pál Vasvári’s socio-historical perspective presents an apt analogy:

“The movements of our nation resembled those of a clock. […] The wheels of the clock were the Diet in Pozsony (Bratislava), and they did not want to turn. […] Springs were needed to set the wheels in rapid motion − the revolution in Pest was that spring. Then, swiftly and suddenly, the wheels began to whirl. […] The clock hand reached Vienna and pointed to the final moments of Metternich’s politics. After three hundred years of silence, the clock struck, sounding the death knell of the Viennese cabinet.”

Perhaps, even if Kossuth could not accept this idea, one year after the “little Pest uprising, his exceptional political instincts told him that this day was no longer merely about itself, but had become a symbol for everything that happened in the country thereafter. For this reason, on March 12th, 1849, he approved the decision of the National Defense Committee ( the country’s provisional government), which stated:

“March 15, as a historically significant day for Hungarian freedom and independence, is to be celebrated by the entire nation."

Without doubt, we can acknowledge that Petőfi the politician possessed an extraordinary instinct: one that recognized the historical moment, grasped the challenge, and − together with his devoted followers and the listening masses − devised and carried out an appropriate course of action. This instinct was not that of a career politician. The unfortunate and well-known circumstances that led to his defeat in the election for the first popularly elected parliament were due not only to the scheming of his opponents, but also to his own shortcomings.

The world of professional politics is somewhat like the army: success depends on following many rules. Petőfi’s unrestrained, impetuous, and emotionally incendiary personality − naturally ideal for poetic genius − was better suited to stand alongside a revolutionary commander such as the Polish General Józef Bem. The historically shaped community we call the Hungarian nation remains indebted to that fortunate encounter on March 15: an event set in motion by the exceptional political instinct of a poet and imminent leader of the people, together with the unique circumstances of that historical moment.

Thus emerged the situation that Lajos Kossuth had already described in 1846, when reflecting on what makes political action truly effective: “Only he who belongs to his own age can wield lasting influence; he who outruns his time lives only after death, while he who lingers behind is dead even in life.”

(translated by Andrea Thürmer and John Puckett)