The history of 1848-1849 is now one of the defining chapters of Hungarian national mythology. It has elements of myth, for it is full of stunning and dramatic scenes, with fearless warriors and loyal servants arrayed against intriguers and traitors, turncoats and bandits. Flipping through the scrapbooks of the 19th century is like witnessing the scenes of a great multi-act drama.

As with all myths, the history of 1848-1849 embraces both fact and fancy. The myth-creating commenced with the “great year” itself, since there is no reality that cannot be made more pleasing when imbued with legend. Thus arose the myth of Sándor Petőfi reciting the National Song on the steps of the National Museum; thus, one penny-dreadful scribe had Lajos Kossuth reciting a prayer on the battlefield of Kápolna, while another had him utter it on the banks of the Danube at Orsova; and thus, Artúr Görgei, perhaps the best commander of the Hungarian War of Independence, became, in Mihály Vörösmarty’s verses, “a miserable scoundrel who sold his country out in the most disgraceful way.”

The myth-making of 1848-1849 has had its negative components alongside those deemed positive. These essentially reflected the profound national disappointment caused by the defeat and suggested that somewhere, somehow, the Hungarian people “went astray,” that the nation’s leaders made errors from the very start that foreshadowed the inevitably tragic end.

Széchenyi or Kossuth?

The conviction that “[István] Széchenyi should have been followed and listened to instead of Kossuth” is ineffaceable from Hungarian public opinion – this, despite the fact that Széchenyi's reform policy was hardly acceptable to the Hungarian public precisely because the Viennese court refused to vouchsafe even this moderate form of opposition. And it is also a fact that while Széchenyi, upon hearing the news about the overthrow of King Louis Philippe of France during the revolution of February 22-24, 1848, lamented, “Why didn’t we kick out our two Louises long ago?” – meaning Lajos Batthyány and Lajos Kossuth – he was praising the same two men in mid-March following the success of their risky policy, averring that they had gained as much for the country as his own policy would have achieved in perhaps twenty years.

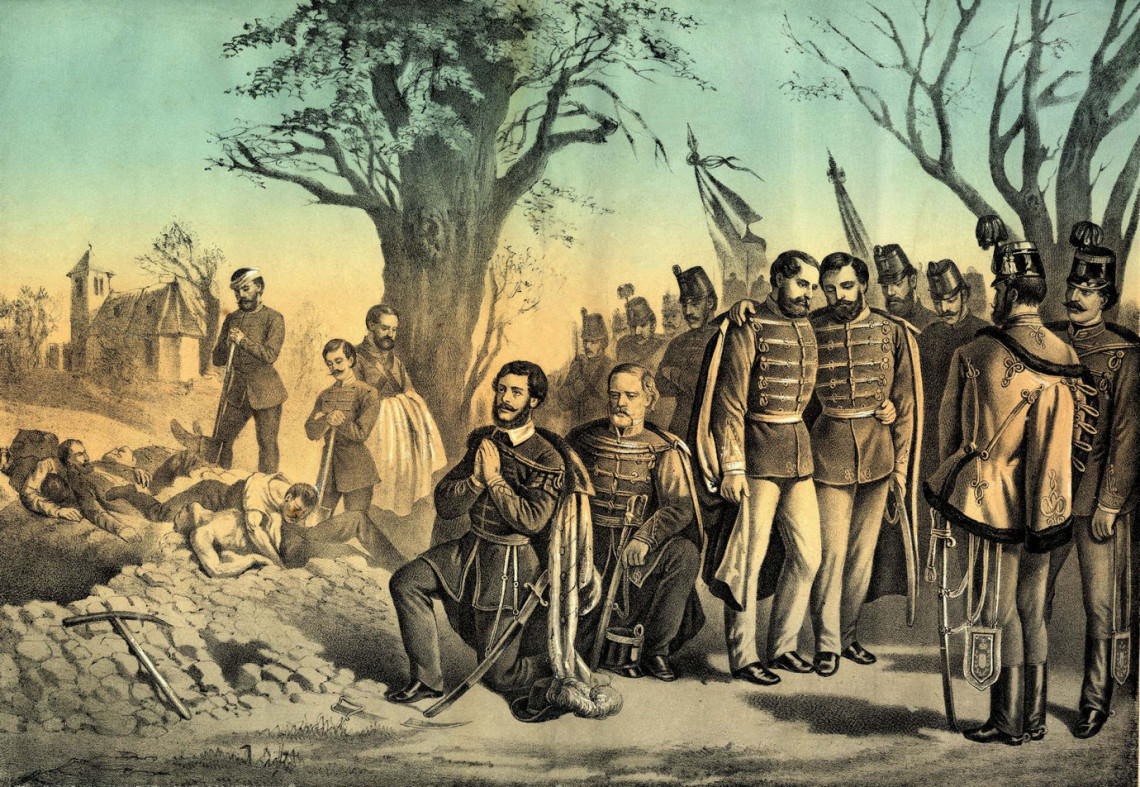

Kossuth praying after the Battle of Kápolna, February 27, 1849. Lithograph by an unknown Viennese painter, mid-19th century.

However, it is also a fact that by the summer of 1848, Széchenyi was already concerned that Kossuth was being overly belligerent toward both the national-minority movements and the Viennese court, even though success on both fronts, according to Széchenyi, was hardly feasible at the same time. His convictions only grew stronger after the crushing of the European revolutions and the consolidation of Austria’s position as a great power; under such conditions, a conflict with both Vienna and the national minorities could spell Hungary’s ruin. “I have read it in the stars,” wrote Zsigmond Kemény, “blood, blood everywhere! Brother will slaughter brother, and race will slaughter race, mercilessly and madly. Crosses shall be drawn on the houses to be burned. Pest is distant, and raiding forces are tearing apart everything we have built. Ah, my life has gone up in smoke, and the name of Kossuth is emblazoned across the heavens – flagellum Dei!” Likewise, Széchenyi feared the coming struggle would become a civil war and that the radicals, led by Kossuth, would settle accounts with their former political opponents – as happened under the Jacobin dicatorship, during the French Revolution.

On September 5, Széchenyi’s nerves gave out and he left the capital, accompanied by his doctor, Pál Balogh, never to return to Hungary. He was checked into a mental asylum in Döbling, near Vienna, to restore his nerves. The “great war,” the war of Hungarian independence, broke out in earnest on September 11, six days after Széchenyi’s departure, when the forces of the Croatian Ban, Josip Jellačić, attacked Hungary. But Széchenyi's fears were ultimately unfounded: Hungary did not slip into civil war, there was no Jacobin dictatorship, and the country survived the conflict.

A caricature ridiculing Kossuth’s and Széchenyi’s economic policies. Watercolor by an unknown artist, mid-nineteenth century.

The declaration of independence and Russian intervention

The conviction that the Hungarian Revolution and the War of Independence were hopeless endeavors from the start is likewise predicated on the fact that the Habsburg Empire, as a member of the Holy Alliance, could count on Russian intervention, and this was specially confirmed by the Russian-Austrian treaty signed in 1833 in Münchengrätz.

A young Emperor Franz Joseph I

There is another view regarding this “charge,” namely, that Tsarist Russian intervention in the summer of 1849 – the intervention that decided the fate of the Hungarian War of Independence – was provoked by Kossuth’s irresponsible policy of dethroning the Habsburg dynasty on April 14, 1849, and declaring independence. It was Kossuth’s actions that provided the justification and legal basis for Russian intervention; otherwise, the Western powers would have prevented the Russian army from taking action.

These views are mutually exclusive, however, since if Russian intervention was a foregone conclusion, then it could not have been provoked by the dethronement and declaration of independence. If, on the other hand, the decisions of April 14, 1849, were the cause of the Russian intervention, such an intervention was illegitimate, and the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence were not hopeless undertakings at the outset.

Already in March 1848, the majority of Hungarian political figures were aware that armed intervention on the part of the “northern collosus” – Tsarist Russia – could occur at any time. The Hungarian chancellor, György Apponyi, had already warned Széchenyi about this at the beginning of the month, and Kossuth had also taken this into account when he referred to it in his speech of March 3, 1848, stating that, “if there were a man in Vienna who, at the dynasty’s expense, would flirt with an alliance of absolute powers for the sake of his own short-lived power, he should be aware that there are powers that are more dangerous as friends than as enemies.”

Following the Russian occupation of the Romanian Danubian principalities in September 1848, one of the first things the Hungarian Batthyány government did was to ask the Russian ambassador in Vienna about the reasons for the Russian maneuver, but the answer was reassuring: they had been forced to invade in the interests of maintaining the internal tranquility of the empire and “wished to have good neighborly relations with the Hungarian people and would take no hostile steps towards Hungary as long as they do not see any gathering of troops and arms in the heart of Hungary that they would deem threatening.”

Tsar Nicholas I was more interested in developments related to German unification than matters playing out in Hungary and had contemplated intervening in Germany until April 1849. He also acknowledged with satisfaction the successes of the Austrian imperial-royal troops in the autumn and winter of 1848. The idea of intervening in Hungary first occurred to him when he learned that Polish General Józef Bem, who was commanding Hungarian troops, might want to invade Bukovina. From then on his letters deal increasingly more with the pace of military developments in Hungary and possible intervention. By the end of March 1849, it had become increasingly obvious that the Austrian imperial-royal army was unable to suppress the Hungarian “rebellion” on its own.

Henceforth, Russian intervention became a matter of increasing discussion in both Vienna and Buda. In Vienna, the court first wanted to increase the size of their Hungarian force with imperial-royal troops from Bukovina and Galicia so that the latter would be replaced by Russian occupying forces in their original locations. Field Marshal Windisch-Grätz, however, regarded the intervention of at least 50,000 Russian soldiers in Hungary as necessary already on March 24. The field marshal’s suggestion played some role in altering Franz Joseph’s position, but the success of Hungarian arms in the spring campaign meant most political figures saw no other solution. Negotiations for preparing for the intervention began at the end of March, and an official request was made on April 21. Finally, on May 1, Franz Joseph addressed Tsar Nicholas I personally in a handwritten letter.

Theoretically, the news of dethronement and the declaration of independence, issued on April 14, 1849, could have justified the official request for help, as the news could have reached Vienna within the week. (In one of his works, the Hungarian historian Domokos Kosáry avers that since the news was known at the Hungarian headquarters in Léva (Levice), in what is now western Slovakia, on April 17, the news could have made its way to Vienna as well by that time.) However, the first appearance of the news in Austrian operational documents is in an intelligence report compiled in Magyaróvár, in western Hungary, on April 30, 1849, which arrived in Vienna the following day and appeared in the newspapers.

Thus, news of the dethronement and the declaration of independence could hardly have been the motivation for the requested Russian intervention, which had been set to paper ten days earlier, on April 21. “All the better,” wrote Franz Joseph to his mother, the Archduchess Sophie, when he heard the news, which also suggests that the dethronement and declaration of independence “came in handy” as a justification for invoking intervention, but not as the underlying cause.

The Hungarians or the non-Hungarians – who was responsible?

The Hungarians or the non-Hungarians – who was responsible? Both professional and popular historiography in the post-1945 decades have successfully fixed public opinion in the view that the primary responsibility for the tragic clash between Hungarians and non-Hungarians in 1848-1849 lay with the Hungarian political elite, which was in power in 1848 and refused to accept the legitimate claims of its fellow nationalities. This view essentially dates back to the Kossuth critique of the Compromise and was also a dominant element of the early twentieth century radical view of history, which – in retrospect – was confirmed by the break-up of the Habsburg monarchy and historic Hungary with it in 1918.

Although national movement among the fellow ethnicities living alongside the Hungarians had already developed during the Reform Era (1825-1848), Hungarian political circles tended to see them as the product of Austrian court intrigues, Pan-Slavic conspirators, or paid Russian agitators, with the former playing no small role in the rise of Croat and Slovak national movements. The Romanian and Serbian national movements, on the other hand, seemed less formidable and threatening; thus, the Hungarian political elite was no doubt surprised by the strongly expressed demands the representatives of these fellow nations formulated in the spring of 1848.

The dismissive attitude exhibited by the Hungarian political elite in the spring of 1848 had two important and mutually dependent reasons. One reason was that Hungarian political leaders linked autonomous national life with territorial autonomy; that is, if the co-nationalities (as minority language peoples were called at the time) living within Hungary at that time were to be recognized as independent nations, then this would imply the designation of an independent territory for them.

Although the Hungarian side was willing to recognize the Croats as a nation because Croatia was an existing entity, the Hungarians refused to do so in the case of the other co-nationalities, claiming that their territorial self-government had no historical legal basis in Hungary. The other, related, reason was that once the Hungarian political elite had managed to regain control over the lands of the Hungarian crown, the idea of dividing the country along ethnic lines seemed psychologically impossible.

It should also be mentioned that the Hungarian government did not shy away from trying to fulfill the legitimate wishes of the co-nationalists, but in view of the difficulties in realizing their demands, it asked for time and patience – something the nationalist movements were not exactly generous with in the spring of 1848. The Serbs had already taken to arms in May 1848, Romanian elements in Transylvania were also preparing for an uprising, and the Croatian Ban Jellačić had already broken off relations with the Hungarian government in April.

A meeting of the Croatian Sabor in Zagreb, 1848. Print after a painting by an unknown artist.

Resolution of the issue was also complicated by the fact that the union of Transylvania and Hungary had taken place only two months after the April laws of 1848, which had abolished all noble privileges and instituted democratic parliamentary elections, had been ratified. The application of such laws in Transylvania would have been difficult even if the largely Romanian peasant population wasn’t already in turmoil. The democratically elected parliament formed a special union commission to draft laws applicable to the special conditions in Transylvania, but the situation in the region had already completely deteriorated by the time it had completed its work.

Finally, it should be mentioned that there were no existing templates for resolving nationality issues in Europe that Hungary could turn to at that time. In fact, dominant nations at this time – be it the English against the Irish, the French against the Bretons and others, or the Russians and Prussians against the Poles – used a wide variety of forced assimilation methods against their minorities. In contrast, the Hungarian authorities aimed at cultural assimilation at most and rightly argued that in a multilingual country there must be a single state language, and in Hungary it was natural that this should be Hungarian.

It should be noted that the Hungarian side was in the end willing to surrender some of the principles of 1848. A 17-paragraph bill proposed by Prime Minister Bertalan Szemere on July 28, 1849, and passed by parliament – although not granting territorial autonomy – did recognize the right of the separate nationalities to free national development and, to this end, granted them extensive language rights in municipal, ecclesiastical, and legislative life. In doing so, the Hungarian government accepted the demand of the various nationalities living within the country to exist not only as cultural and religious communities but as political communities as well.

The Zalatna (Zlatna) Massacre, October 23, 1848. Woodcut by unknown artist, mid-19th century

Haynau as a Hungarian leader

One of the strangest myths concerns the Austrian general Julius Jacob von Haynau, known as the Hyena of Brescia (in Italy) and the Hangman of Arad (in Hungary). MP János Pálffy, a member of the National Defense Committee of the Hungarian parliament in 1848-1849, writes in his memoirs that Haynau offered his services to the Hungarian government in early 1848, “who, being refused, resigned himself to active service with Austria, saying that he felt that he had a great part to play in the Hungarian revolution in one way or another.” In other words, if the Hungarian government had been a little more receptive and accommodating, the executions in Arad and Pest might not have taken place – or at least Haynau would not have been the one to carry them out.

However, the exact opposite is true. Ferenc Asserman, later a Hungarian army colonel, who was stationed at Temesvár (Timișoara) at this time, writes in his memoirs that “what is certain is that the [imperial] army headquarters in Temesvár could not be accused of any liberal, constitutional, or even nationalist sentiment at that time.” Haynau, then a lieutenant general in command of a division in Temesvár, “exclaimed, while commenting on the political events of the day in the early spring of 1848, ‘Let His Majesty give men a couple of regiments and I will crush the Hungarians.’ And such was how all the other inveterate old generals living in the same atmosphere likely thought.”

Haynau’s antipathy later led to a strange altercation. On March 31, 1848, Haynau began to berate the Hungarians in the presence of János Damjanich, the Serbian-born captain of the 61st (Rukavina) Infantry Regiment, and several other officers, calling the Hungarians Kossuth’s dogs, ruffians, outlaws, and a mongrel people. None of the officers dared to speak, but Damjanich – who, despite his Serbian origins, was an exceptionally enthusiastic Hungarian – suddenly spoke up: “General, sir! I am a Hungarian, and I cannot tolerate you insulting my people and its best sons in my presence!” Haynau was taken aback and then said mockingly, “Since when did you become Hungarian?” “Since the moment, general, sir, that I have been able to understand that anyone born in Hungary is a Hungarian citizen and is obliged to consider Hungary his homeland and to defend its legal rights, whatever his standing.” Haynau turned on his heels, and Damjanich received orders the very next day to leave for his regiment’s battalion fighting in Italy.

The incident caused a major scandal. On April 2, Sebő Vukovics, the future minister of justice in 1849, reported to Gábor Klauzál, minister of agriculture, trade, and industry and member of the Provisional Committee of Ministers, that “among the local officers there are a small number who dare to openly express sympathy for our freedom,” and Damjanach was among these few. “But there is one general,” he continued, “named Haynau, who spreads hatred and ridicules our revolutionary movements.” Vukovics reported on the exchange of words between Damjanach and Haynau and how Damjanach was subsequently ordered to northern Italy. “This gives a bad impression here and encourages the reactionaries who rejoice at every gesture that suggests that a power other than the national government is in charge.” He thus recommended that Damjanich be recalled as soon as possible.

This wasn’t Haynau’s only outburst. On May 7, he had words with the engineer Sándor Asbóth at the main guard post at the headquarters of the Temesvár fortress. That same day (perhaps not unrelated to the exchange of words with Asbóth), he petitioned the imperial-royal minister of war, Theodor Baillet de Latour, to grant him permission to lead his own regiment in the operations in northern Italy. The original petition request has been lost, and its contents are known only from Latour’s response dated May 12. In it, he expressed his pleasure at Haynau’s true soldierly sentiments and his brave martial spirit but stated that he could not grant the request under the present circumstances.

Upon receiving Latour’s reply on May 12, Haynau departed for Graz and reportedly asked to be granted retirement. On May 31, Sebő Vukovics, who had been the royal commissioner of the Southern Region since May 24, reported to Bertalan Szemere, the minister of the interior, that Haynau had left Temesvár on a three-month leave of absence. “I hope he never comes back,” he wrote. In Sebő Vukovics’s recollection of the events, “[Haynau] was a hater and complete enemy of the Hungarian government from the very beginning,” and “he obviously voiced his enmity among other members of the military.” At the same time, “the supreme military court generally responded to complaints lodged before it regarding Haynau, stating that the general’s views were common knowledge and that his outbursts deserved contempt.” No one suspected then that this despised individual would become the emperor’s commander-in-chief and Hungary’s executioner a year later.

Damjanich’s farewell

The other main character in Haynau’s first incident in Temesvár, János Damjanich, enjoyed a meteoric career in the Hungarian army following his return home in June 1848. On June 20, he was appointed major and subsequently promoted to lieutenant colonel and brigade commander on October 14 and then to full colonel and division commander in the Banat Corps on November 25. He and his troops won several victories over the Serbian rebels: at Strázsa (Temesőr) on November 9, at Károlyfalva (Banatski Karlovac) and Alibunár (Alibunar) on December 12, and at Jarkovác (Jarkovac) on December 14-15. He was promoted to major general of the Hungarian army in December but was placed on medical leave until early January 1849 due to illness. On January 9, 1849, he was appointed commander of the Banat Corps. It was in this capacity that Damjanich was tasked with evacuating the Banat, via Arad, to the middle Tisza, where defensive positions were to be taken up.

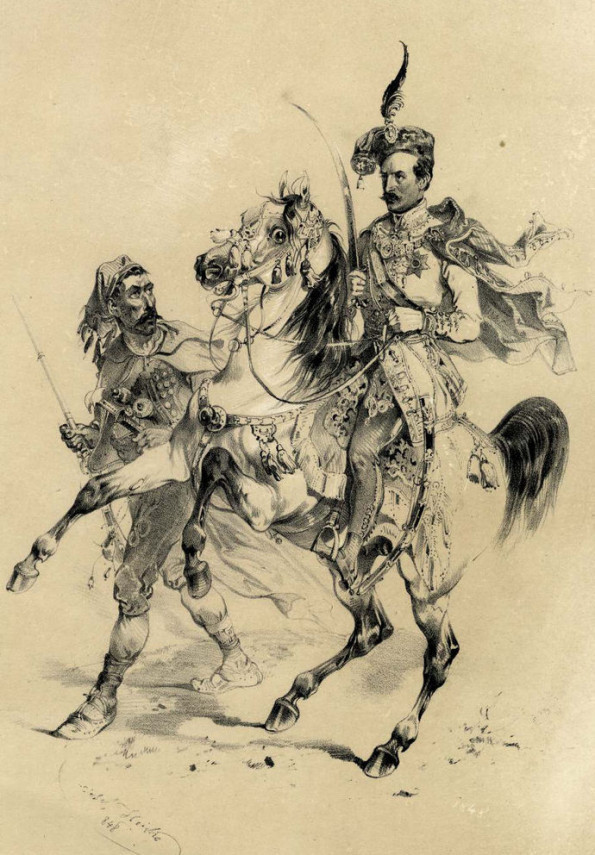

János Damjanich. Lithograph, Rezső Grimm

It was with a heavy heart that the Hungarian government decided to evacuate the Southern Region, including the Banat, and it was perhaps with an even heavier heart that the troops carried out their orders. It is no surprise that the war that broke out in the south in June 1848 was not a simple military conflict but took on the aspect of an ethnic war between Serbians and Hungarians. During the ensuing fighting, the local German and Hungarian population suffered heavily at the hands of Serbian insurgents, who wanted to create a Serbian Vojvodina, or autonomous province, in the area by destroying defenseless settlements and massacring or expelling their inhabitants.

The retreating Hungarian forces were followed by long caravans of civilians, with those staying behind uncertain whether they would fall victim to invading Serbian forces or even to their Serbian neighbors.

According to legend, General Damjanich, who had a rather fiery nature, intended to protect the civilian Hungarian population with the following proclamation, which was unusually bold even for Hungarian-Serbian relations of the time. “You dogs! I am leaving as your enemy, but I will return as an avenger. If you dare to attack the Hungarian people in the meantime, I will wipe you off the face of the earth so that not a single seed of Serbs will remain, and then I will shoot myself in the head as the last Serb.”

The proclamation was first published by the Hungarian novelist and revolutionary Mór Jókai in the February 22, 1849, issue of the Debrecen-based Esti Lapok [Evening News], in a column titled “Charivari” [Cat Music]. The proclamation must have quickly become popular because on February 25, János Kollár, a Békés County delegate from Törökszentmiklós, presented it to the Békés County Committee.

Jókai also did his part to popularize the proclamation after the war, publishing the text, albeit in a somewhat altered form, in one of his best short stories, “A két menyasszony” [The Two Brides], as part of his anthology Forradalmi és csataképek 1848- és 1849-ből [Revolutionary and Battle Stories from 1848 and 1849], published in 1850: “You dogs! I’m leaving. But I’ll be back. If you dare make a move in the meantime, I’ll wipe you off the face of the earth, and to make sure the seed of the Serbs is destroyed, I’ll shoot myself as the last Serb!”

In 1851, General György Klapka provided a German translation of Damjanich’s proclamation with slightly different content when writing his memoirs, and it was later translated back into Hungarian by some later authors, such as Rikhárd Gelich and György Gracza. Gracza also dated the proclamation: according to him, Damjanich issued it on January 16, 1849, in the town of Versec (Vršac), in what is now northern Serbia. Among Austrian historians, Josef Alexander Helfert, the most detailed historian of the 1848-1849 winter campaign, also considered the proclamation authentic.

However, a closer examination of the text and the circumstances surrounding its supposed origin shows that we are dealing with a fictitious text or, to put it more plainly, a simple forgery. We will start with the date of January 16, 1849, in the town of Versec, as proposed by Gracza. This is most certainly incorrect, as Damjanich was in Nagybecskerek (Zrenjanin) between January 15 and 20 and headed from there straight for Arad together with the Banat Corps under his command. Although part of the Banat Corps did indeed clash with the pursuing Serbian corps in the town of Versec on January 19, Damjanich was not present in this battle.

As for the text itself, Damjanich was witness to the fighting in the south starting in June 1848, saw all its cruelty, and was aware of how mercilessly the Serbs treated their prisoners and the inhabitants of the occupied towns and villages. Is it really possible that, in a situation where Damjanich knew for sure that he would be unable to protect the remaining civilian population, he would wantonly provoke the Serbs even more? His actual reluctance to do so was such that – contrary to Kossuth’s suggestion – he refused to take hostages from among the Serbian population of the ceded territories because he feared this would only worsen the situation for the Hungarian population remaining behind.

Massacre of Hungarians by Serb insurgents in Fehértemplom (Bela Crkva), August 19, 1848. Colored lithograph by Vinzenz Katzler

On January 17, Damjanich did indeed write to the commander of the Serbian-Austrian Corps, Major General Kuzman Todorović, from Nagybecskerek, but in this letter – reflecting on the proclamation issued by Todorović upon assuming the corps command calling on the Serbs to take revenge – Damjanich asked his opponent to spare the peaceful civilian population during his advance. He also stated that he would publish both Todorović’s manifesto and his own response in the newspapers so that the world could judge which of them was to blame for a future without redemption. He also asked Todorović to reflect on whether the Serbs were shedding their blood on the right side in the cause of Serbian freedom and whether the Serbs could rightly expect the ruling house to accede to their wishes if Austria were to win the war. Is it really conceivable that Damjanich could have addressed the Serbs with two such diametrically opposed messages in such a short amount of time?

The authenticity of the alleged proclamation is also contradicted by the fact that no copy of the proclamation has ever been found – this despite the fact that such a provocative text would have been beneficial for the Serbian-Austrian command in the winter of 1849 and for the Austrian authorities after August 1849 to demonstrate the brutality of the Hungarian side.

Finally, the text of the proclamation is also contradicted by Damjanich’s contemporaries themselves. Sebő Vukovics, for instance, who was the plenipotentiary national commissioner for the Banat at this time, knew nothing about this proclamation, even though he was with Damjanich during those days. József Zalár, who was appointed field historian in mid-March 1849 and served alongside Damjanich, believed that “Damjanich’s farewell [proclamation] is not a documented certainty, but because it characterizes the mood of the time and fits into the framework of Damjanich’s strong Hungarian character despite being a Serb, it was widely circulated.” The idea of advocating genocide followed by suicide is also contradicted by what István Elekes, one of Damjanich’s officers, recorded. According to him, on April 27, 1849, Damjanich said the following in the company of his officers: “If we come to terms with the Germans, then don’t look for me in the army, but come to Magyarát (Măderat); there you will see an old Serb hoeing the vine and drinking last year’s wine – that will be me.”

The vanquished warrior – Haynau’s London escapade

One of the most infamous episodes in Haynau’s biography – one that also caused an international sensation – concerns his visit to London in 1850, when the workers of an English brewery thoroughly inconvenienced the general, who was visiting the enterprise. A recent legend has it that this was due to a small number of Hungarian emigrants working at the brewery who recognized the executioner by his distinctive moustache.

The general, who ended the Hungarian campaign with a triumph, was removed from his position and placed in retirement in early July 1850 as a result of pardon decrees he had issued prior to the monarch’s recognizance. He then spent a short amount of time resting at the Gräfenberg Spa, where he received news of his wife’s passing. It was then that he decided to make a tour of Europe. His itinerary involved traveling from Germany to Belgium, from there to England, and then to Spain. He was well received in Germany. In Brussels, however, the former Austrian foreign minister, Metternich, tried to dissuade him from going to England, saying that Haynau’s name had a very bad reputation in the island country thanks to the activities of Hungarian emigrants. Baron Neumann, the Austrian ambassador in Brussels, offered the same advice, having received a letter from Baron Koller, his counterpart in London. Haynau, however, stuck stubbornly to his itinerary.

Once Haynau arrived in London, Koller tried to persuade him to at least cut off his notoriously long moustaches, but he refused. On September 4, he visited the Barclay and Perkins brewery, where what Metternich, Neumann, and Koller had feared took place. According to one Austrian memoir, a Viennese refugee named Gustav von Frank recognized Haynau and informed his fellow workers. The workers assaulted him and even pulled on his famous long moustaches; nevertheless, Haynau managed to escape to a nearby house, although with great difficulty.

Julius Haynau. Lithograph by Joseph Kriehuber

A very detailed description of the event is given by the Hungarian émigré Jácint Rónay. According to Rónay, Haynau made a peaceful tour of what was perhaps the largest brewery in the world, and when he was led to the guest book at the end of the visit, an employee was shocked to see how infamous a guest he was. (According to another source, Haynau wrote his name in the visitors’ book at the beginning of the tour, and it was after this that news of the “Austrian butcher’s” visit spread). The employee then passed on his discovery to the other workers: “Unrest was brewing and if the guide or Haynau himself had been paying attention, he could have easily fled to the offices, but no one paid attention to the unusual liveliness among the workmen. The general continued on, but the moment he entered the courtyard, a large bundle of straw was thrown from the third floor onto the tall visitor’s head. This was the signal, and all at once he was besieged by a sea of muscular arms, and a whole torrent of the most insulting expressions were tossed his way as he was pushed and pursued... What could he do? He fled out the gate and around a corner of the building along the banks of the Thames… Here the workers were joined by people from the streets, and they pursued the fugitive everywhere amid the dust and the mud, prodding him with sticks and brooms… Thus, staggering and run ragged, he arrived at Mrs. Benfield’s pub, at least a thousand yards away, where, after much struggling, he found refuge in a corner of the establishment. At last the police arrived in force, and the general, now deathly pale and barely recognizable, was whisked across the Thames, not along the nearby bridge where they feared a renewed onslaught by the angry mob, but by boat, and only on the opposite bank was he finally put into a hired cab to be taken to the safety of his lodgings (Trafalgar Square).”

Haynau did not press charges for the abuse and soon left London, traveling to Ostend and then, via Aachen, to Vienna, where he was told – according to Hungarian news reports – that “there were definitely Hungarian refugees among the people, and they must have prepared the whole thing. Haynau denied this with great indignation, saying that the Hungarian defeats his enemy in battle but does not do anything disgraceful, and that the Hungarians love him more than what these people were capable of.”

A similar statement by Haynau was also noted by the British Chargé d’Affaires in Vienna, Magenis: “Although he didn’t know on what grounds to say so, he was convinced that the attack on him had nothing to do with Hungarian refugees.” Thus, Haynau’s beating in London cannot be credited to the Hungarian émigrés; rather, it testifies to the sympathy a broad swath of the British public felt towards the Hungarians and their indignation at the reprisals carried out in Hungary.

Brewery workers and Haynau as the Austrian butcher. Woodcut by an unknown English artist, mid-19th century

Haynau’s unpopularity in England did not begin with the execution of the 13 Hungarian generals in October 1849, however. His proclamations against the inhabitants of the Hungarian capital in July 1849 already made a bad impression within British political circles. The Hungarian political figure Ferenc Pulszky offered an interesting explanation for Haynau’s bad reputation. According to him, the English were accustomed from their own history that “he who takes up arms against his prince and fails to win pays for his wicked intent with his life, and this was taken for granted in Hungary’s case as well; although they felt pity for the victim and disapproved of the victorious side’s conception of power based on the scaffold, they did not deny its legitimacy.” The British public was shocked, however, by the news that Haynau had publicly flogged the female Hungarian revolutionary Franciska Maderspach. The English regarded such an act as “lacking moral feeling and as a sign of barbarous cruelty such that Western civilization in the present age thought impossible.” Just as the War of Independence was identified with Kossuth and Bem, “all the cruelty and ignominy of the reaction was attributed to Haynau among the public.”

The London incident was repeated again almost two years later. In the summer of 1852, Haynau spent a few weeks at the Ostend baths, whence he traveled to Brussels to attend a concert at the Waux-Hall. He was staying at the Hôtel de Flandre, where a Hungarian refugee recognized him and immediately announced his presence. When Haynau arrived at the concert hall, the crowd first murmured and then began to shout, “Be gone! Shame, executioner! Shame, woman beater!” According to the Hungarian writer Miklós Jósika, Haynau was already being labeled a hyena, an executioner, a woman beater, and a scoundrel by the ladies in Ostend, and it is said he received a similar reception in Paris.

The Hungarian émigrés did everything they could to make Haynau’s European jaunts disagreeable. The Hungarian writer László Teleki had already challenged him to a duel in an open letter on September 11, 1850, following the London incident, and did so again in the autumn of 1852. Such openly published attacks obviously did little to help the aging lieutenant general’s health. Haynau was forced to experience the fullness of an imperfect world: the empire, which he did everything he could to save, was unable or perhaps unwilling to protect him from insults.

The sacrificed flank guard– the Battle of Debrecen

The myth of General Artúr Görgei’s betrayal constitutes a separate chapter among the legends of the War of Independence. The way posterity has interpreted the battle of Debrecen on August 2, 1849, provides an excellent example of how myths are born. According to this, Görgei had an antipathy for Major General József Nagysándor, the commander of the I Corps, because he considered him Kossuth’s man and thus his enemy. Thus, in early August 1849, Görgei entrusted him with the task of flank guard for the Army of the Danube and even ordered him to engage the Russian main army near Debrecen. And when this occurred, Görgei did not rush to the aid of his lieutenant, which is evidence enough of his ill intentions.

Debrecen, August 2, 1849. Colored lithograph by an unknown artist

The facts, however, reveal something different. To summarize: It is true, the relationship between Görgei and Nagysándor was not without its complications. When, upon hearing the news of the declaration of independence in April 1849, several officers at the Hungarian army headquarters spoke of the need for a military dictatorship, Nagysándor declared – in Görgei’s presence – that “if anyone were to dare become a military dictator, there would be more than plenty in the Hungarian army who would point a pistol at his chest, and if no one else was forthcoming, I would be first in line.”

József Nagysándor. Watercolor by an unknown artist, mid-19th century

As for the events in question, Görgei, upon crossing the Tisza River, divided his army in two on July 30, 1849, at Nyíregyháza: He sent Nagysándor’s I Corps, the army’s most intact formation, to march along the route of Hadháza, Debrecen, Derecske, and Berettyóújfalu to cover the army’s flank, while the army’s two other corps were sent on a line running from Nagykálló, Nyíradony, Vámospércs, and Nagyléta to Kismarja. Nagysándor’s corps had not seen action since the battle of Vác on July 17, while the other two corps had fought several battles along the Sajó and Hernád rivers.

On August 1, Major István Pongrácz, chief of staff of the I Corps, reported to the army high command that the Russian vanguard had entered Balmazújváros, northwest of Debrecen, the previous night. Since the I Corps lacked significant strength, Pongrácz suggested that the corps should depart for Debrecen as soon as possible and engage the enemy there. The Hungarian command approved the plan, stating that the corps should repel the enemy advance if it reaches Debrecen and then continue its retreat in accordance with instructions issued earlier. Thus, it was not Görgei who initiated the battle, but the corps commander, or more precisely, the chief of staff.

At 8 am on the morning of August 2, Pongrácz reported to the high command that the corps had arrived in Debrecen and was facing 15,000 Russian troops. The corps command took the necessary steps to repel the enemy advance and set out the next day for Derecske, south of Debrecen. That same day, the I Corps clashed with the main Russian army led by Ivan Paskevich and suffered a major defeat against a force nearly five times its size.

Ivan Paskevich. Lithograph, Eduard Kaiser

It was often asked later why Görgei did not rush to Nagysándor’s aid and what assistance he could have provided the I Corps once embroiled in battle if he had. Simply, the I Corps had been tasked with covering the flank of the other two corps while they retreated, so if Görgei came to Nagysándor’s aid from Vámospércs, he would have nullified the entire purpose of the operation. If Nagysándor had followed his commander-in-chief’s orders to the letter (as issued on the basis of his own chief of staff’s report and recommendation), he could have left the battlefield without suffering major losses after having repelled the Russians and then continued his retreat towards Nagyvárad (Oradea).

When Görgei, at his headquarters in Vamospércs, heard the roar of cannons from the direction of Debrecen, he naturally thought that Nagysándor was fulfilling his task. Even if the III and VII Corps had set off from Vámospércs, 25 kilometers from Debrecen, at 1:55 pm (after having already marched the 20 kilometers from Nyíradony in the heat of the day) upon hearing the first roar of the cannons, it would have taken the main body of the army between six and six and a half hours to reach the battlefield, arriving around 8:30 or 9 pm, without any rest. The battle of Debrecen, however, had already finished between 4:30 and 5 pm. The result then would have been nothing more than a catastrophic defeat for the two Hungarian army corps, exhausted by long forced marches and facing an enemy three times their size.

The “Hungarian” Hentzi

Another myth is that Major General Heinrich Hentzi, who defended Buda Castle against Hungarian forces in May 1849, had been unappreciated by the Hungarian government, and this is why he had switched sides to the Austrians. In this case, there is some basis in fact, as Hentzi, having been born in Debrecen on October 24, 1785, the scion of an originally Swiss military family, was thus considered a native Hungarian and spent a significant part of his military service in Hungary. Hentzi, however, had been a loyal servant of the emperor his entire life, and when General Görgei called on him to surrender Buda Castle on May 4, 1849, appealing to his Hungarian nationality, he replied, “I must declare to you that I am not a Hungarian, but a naturalized Austrian of Swiss origin, and I bear no obligations towards Hungary whatsoever.”

The Death of General Hentzi, April 21, 1849. Lithograph by Vinzenz Katzler

Hentzi was made major general in 1848 and was appointed commandant of the Pétervárad (Petrovaradin) fortress garrison in the fall of 1848. He was arrested by the Hungarian authorities in mid-December 1848 when suspicions arose that he intended to surrender the fortress into the hands of Serbian rebels. He was thereupon sent to Pest, where he was placed under house arrest. He remained behind during the evacuation of the capital, and when Austrian imperial-royal forces entered the city in January 1849, he reported for duty to Field Marshal Alfred zu Windisch-Grätz, who appointed him commandant of Buda Castle. Undoubtedly, Hentzi was also motivated by the “insult” he had suffered at the hands of the Hungarian authorities to perform his duty as thoroughly as possible. Although some suspected Hentzi of treachery, after the castle fell to the Hungarians, his heroic death alone should refute this suspicion. In 1859, Emperor Franz Joseph I posthumously awarded him the Military Cross of the Order of Maria Theresa and elevated his son to the rank of baron.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)