For understandable reasons, none of the successor states created or enlarged at the expense of Hungary in the wake of the First World War had any interest in preserving either memorial sites inherited from the Hungarian state or those generally depicting Hungarian themes and motifs. Instead, the elites of these new states sought to emphasize and render final the new order by renaming streets and institutions and by transforming or even obliterating existing monuments through the occupation of symbolic terrain and the creation of their own representational spaces. They did so with some compunction, however, as they feared the possible success of Hungarian revisionist efforts despite all the voices to the contrary. The new authorities were aware of the harshness and injustice of the Trianon decision, even if only subconsciously, and if not, they were readily made aware of this at the hands of those Hungarians remaining in their former homeland, who speedily embarked upon self-organization once the initial shock had passed.

Although debates over the concept of nation have continued for over two centuries now and are yet to reach a consensus, most agree that its most important characteristic is a similarity in cultural traditions. Such traditions include a common mother tongue, taken in the broadest sense; the partial coincidence of customs and rituals; a history that is at least somewhat shared in nature; and a certain degree of compatibility between collective and individual memory. None of these are exclusive and unconditional requirements for identification with a nation, yet each may play an important role in the latter.

The remains of the Millennium Monument in Dévény (Devín), designed by Gyula Jankovits and dedicated on October 18, 1896. The monument was blown up by Slovak intelligence agents on January 12, 1921, and its remnants fell into the Danube.

The situating of memorials

The long line of monuments established especially in the last third of the nineteenth century and intended to commemorate the past and strengthen the presence of the Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin could be viewed as a tangible manifestation of national unity. This sort of symbolic occupation of space accelerated throughout the millennium and into the early twentieth century, in tandem with the process of Hungarian assimilation and in complete contrast to the strengthening separatist aspirations of Hungary’s ethnic minorities. The former, however, was not really attainable, as only the Germans (Swabians), Slovaks, and Jews became assimilated, and this primarily in the towns, while preventing the latter, as history has shown, proved illusory as language borders shifted in many places – to the detriment of the Hungarians. No matter how much the situating of memorials may have altered the perception of some locality or another, their impact on national consciousness and political processes in the peripheral regions of historical Hungary remained relatively minor.

Nevertheless, their existence should not be underestimated. Since ancient times, various spaces have had a serious, often ritualistic role to play in addition to their own real or putative history. Memorial sites dedicated to the commemoration of past events or important personalities, mostly of local significance, were expanded with new content starting in the nineteenth century. As such, they represented an important force in the formation of national identity and became ceremonial arenas for community attachment in both a broad and a narrow sense, with plaques and statues adorning their spaces. They were intended to express the unity of the past, the present, and the future in the spirit of the notion that “whoever owns the past, owns the present and the future.” This idea proved false, however, in the case of Hungary and her lost territories, as the nation shrank continuously from the autumn of 1918 onwards. From a political perspective, both the central and local authorities of the time regarded the capital invested in the creation of memorial spaces – which sometimes came from public donations – useful both in the interests of their own legitimacy and for the consolidation of Hungarian identity through the partial transformation of the symbolic use of space in localities with a Hungarian, mixed, or mainly ethnic minority population.

The monuments that began proliferating from the 1870s onward and which reached their peak construction both in Hungary and the rest of Europe between 1870 and 1914 almost always bore some local significance. Their main exemplars commemorated the thousandth anniversary of the Hungarian conquest, the Kuruc period, the 1848-49 revolution and war of independence, various Habsburg monarchs (primarily Franz Joseph and Elisabeth), and the heroes of the First World War, and were usually associated with the modernization of public spaces, primarily in the cities but in smaller towns and villages as well. Almost all of them were the object of ceremonial unveiling and consecration in the presence of nationally known or prominent local officials and afforded wide publicity in the press. The statues and memorial plaques erected in this fashion became the sites of regularly recurring dignified events marking significant dates in the calendar, and it was during this period that rituals developed, which to some degree, still function as expressions of nationhood to this day.

It should also be noted in this regard that changes in state power and systems of government – and revolutions especially – have sought to establish their legitimacy first and foremost by suppressing the symbols of the previous era. Countless examples demonstrate the proof of this assertion in 1918-1919, 1944-1945, the years following 1948, 1956, and the Kádár era in Hungary, as well as around the time of the first post-Soviet elections in 1990. And this was even more the case with the successor states that were established after the First World War and those that expanded their existing territory, annexing a greater or lesser portion of Hungarian land.

Statue of Lajos Kossuth in the main square of Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș), designed by Miklós Köllő and dedicated on June 11, 1899. It was toppled on March 28, 1919, along with statues of József Bem and Ferenc II Rákóczi. An Orthodox cathedral was erected in its place while the discarded statue was melted down and used to cast bronze eagles to decorate Romanian military monuments. On October 14, 2001, an exact replica of the statue was erected in Gyergyócsomafalva, Köllő’s native village, having been recast by Csaba Sántha and Tibor Kolozsi.

A terrain of ethnic struggles

In any case, from the autumn of 1918, public spaces also became the terrain of ethnic struggles, and in this regard – compared to earlier times – Hungarians were clearly at a disadvantage. The transition in this respect was also gradual, occurring alongside a forced and constant Hungarian retreat, and one of its first steps was always the damage or destruction of Hungarian monuments. Nevertheless, those that remained were to become prominent arenas for the cultivation of Hungarian identity, all the more so if they were primarily established at the initiative of the local communities.

Hungarian historical scholarship has paid little attention up to now to the cultural aspects of the peace diktat. Perhaps it is because, unlike in other policy areas, the peace agreement contained only a few restrictions in this regard, affecting only a small proportion of public holdings and collections (archives, libraries, museums). The government, therefore, had a free hand in the cultural sphere, and it was partly due to this that by the mid-1920s it was receiving the largest subsidies from the state budget. Nevertheless, the losses – in terms of education, public culture, public collections, the arts, and especially monuments – were painful and difficult to replace and affected memorial plaques and statues most of all, a significant portion of which were condemned to destruction by the successor states.

Monument to Lajos Kossuth, in Arad, designed by Ede Margó and Szigfrid Pongrácz and dedicated on September 19, 1909. On October 10, 1919, the decision was made to dismantle it, and on the morning of March 9, 1921, the side statues were removed, after which the remaining statue was boarded up. On May 30, 1925, the Romanian government issued a decree for its demolition, which began on July 27, 1925. The statue’s remains were first stored in the former riding stables and later in Arad Castle. Its fate after 1956 is unknown.

All this was exacerbated by the fact that the location of the most significant memorial sites – if not the entire cultural institutional system – were subject to the dictates of Trianon, along with towns with a predominantly Hungarian population. Hungary lost five of its six fully functioning regional centers (Zagreb, Pozsony (Bratislava), Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), Kassa (Košice), and Temesvár (Timișoara)) along with three of its six partially functioning centers (Arad, Brassó (Brasov), and Nagyvárad (Oradea)). Of the former category, only Debrecen remained, while of the latter, Hungary retained Szeged, Pécs, and Győr. With the exception of Győr, these were university towns that Kuno Klebelsberg, the former minister of the interior, intended as provincial cultural centers and disseminators of high culture.

The more than ten million Hungarians of the prewar population found themselves divided among four countries with their cultural power beyond post-Trianon Hungary’s borders greatly diminished, partly because intellectuals were heavily overrepresented among the approximately 400,000-450,000 who fled to Hungary. Thus, the intellectual-cultural losses of the prewar Hungarian community were much more onerous than the territorial losses, as the lost lands of the homeland could not emigrate, whereas the intellectuals, the purveyors of high culture, were able to do so, which in turn reduced the ability of those who remained in place to assert their interests.

This was compounded by the fact that after 1918-1920, Hungarian policymakers, hoping for an imminent revision of the treaty, focused on the construction of Hungary as a political nation, believing that the rejection of such would mean accepting the new borders. It is obvious now that this was a mistake, since one of the things that nourishes and deepens Hungarian solidarity is the adoption and promotion of the concept of a cultural nation, one that transcends political borders and includes all those who identify as Hungarian, as against the idea of a political nation.

The blatant disfigurement and removal of statues and memorial plaques within the successor states between the two world wars, however, was a direct assault on this concept of the cultural nation. It not only increased the desperation of the Hungarians living in the annexed lands – who viewed this as a manifestation of the successor states’ anti-Hungarian and culturally inferior and ignorant policy – but also strengthened the popularity of the revisionist “cult” in Hungary. Moreover, it also indirectly increased the resentment towards Western Europe, which had turned a blind eye to the destruction of memorial sites, and towards an “ungrateful” Hungary and its national inward turn.

As former ministerial advisor Ferenc Olay remarked in 1930 in his book A magyar művelődés kálváriája az elszakított területeken 1918-1928 [The calvary of Hungarian culture in the seceded territories 1918–1928]: “The fate of our monuments and statues in the separated territories is most tragic. These were the mementos of a glorious history, in which the thousand-year past of the Hungarian nation dwelled. The relics of this history now largely lie in ruins or reside in storage. Hungarian fine arts has suffered an irreparable loss at the hands of soulless destroyers, with the number of monuments damaged or destroyed so far around 120, and this number, to the eternal shame of Western civilizations, is still increasing even after ten years.”

Statue of St. László (Ladislaus), in Nagyvárad (Oradea), designed by István Tóth and dedicated on September 10, 1893. The statue was dismantled on July 13, 1923, and moved to the garden of the Bishop’s Palace, where it can still be seen today. The statue’s place on St. László Square was replaced by an equestrian statue of King Ferdinand I of Romania.

However, Olay’s rough assessment was valid not only for statues and memorial plaques that had been transferred to the successor states, as there were also cases where considerable sums of money collected for the erection of other statues were confiscated, as in the case of the planned Rákóczi monument in Kassa (Košice) and the Kossuth statue in Szabadka (Subotica).

At the forefront of the vandalization and destruction of Hungarian memorials was Czechoslovakia, which also occupied Transcarpathia. It was followed by Romania and then the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later named Yugoslavia.

Most of the damaged or destroyed monuments commemorated the 1848-49 revolution and the War of Independence, including Lajos Kossuth and the martyrs of 1849, or less often Sándor Petőfi and the reform era, both in the larger towns and numerous other memorial sites, such as Arad, Barót (Baraolt), Boksánbánya (Bocșa), Dobsina (Dobšiná), Érsekújvár (Nové Zámky), Fehéregyháza (Albești), Igló (Spišská Nová Ves), Kassa (Košice), Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), Körmöcbánya (Kremnica), Losonc (Lučenec), Lőcse (Levoča), Magyarittabé (Novi Itebej), Máramarossziget (Sighetu Marmației), Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș), Nagybecskerek (Zrenjanin), Nagykároly (Carei), Nagymihály (Michalovce), Nagyszalonta (Salonta), Nagyszeben (Sibiu), Nagyszőlős (Vynohradiv), Óbecse (Bečej), Ompolygyepű (Presaca Ampoiului), Pozsony (Bratislava), Rimaszombat (Rimavská Sobota), Roskovány (Rožkovany), Segesvár (Sighișoara), Selmecbánya (Banská Štiavnica), Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe), Szabadka (Subotica), Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare), Szinérváralja (Seini), Törökbecse (Novi Bečej), Versec (Vârșeț), Zilah (Zalău), Zombor (Sombor), Zsibó (Jibou), and Zsombolya (Jimbolia).

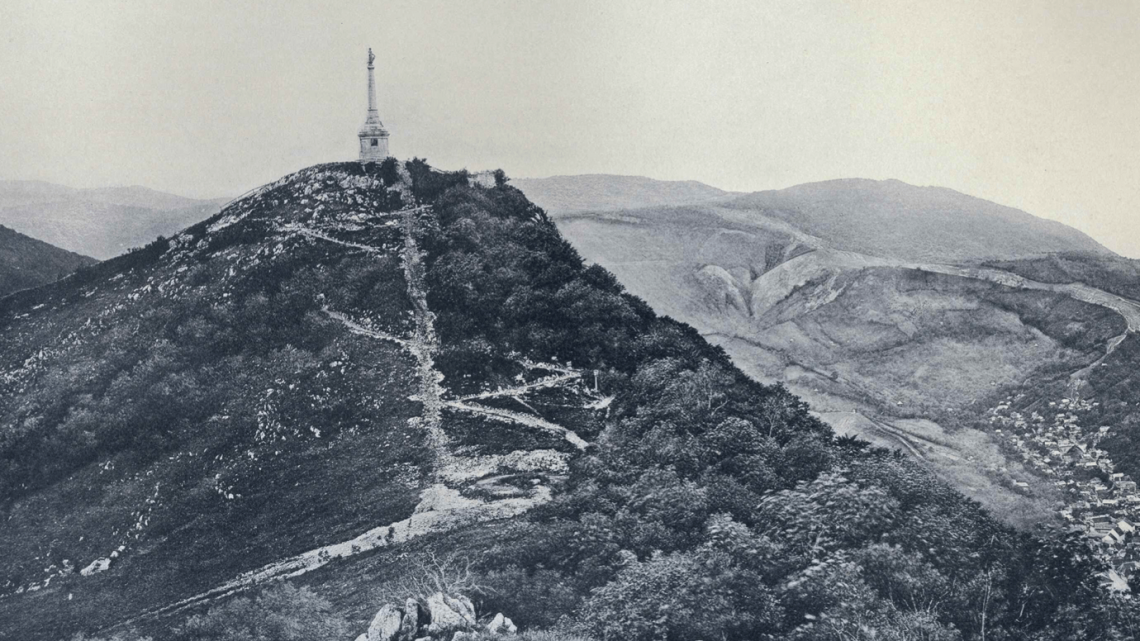

First on the list of losses were the millennium monuments in the annexed towns of Brassó, Dévény (Devín), Gerlachfalvi-csúcs (Gerlachovský štít), Munkács (Munkachevo), Nyitra-Zoborhegy (Nitra-Zobor), Pozsony, Székelyudvarhely (Odorheiu Secuiesc), Vereckei-szoros (Veretskyi Pass), and Zimony (Zemun), and statues and memorial plaques depicting or praising the royal couple Franz Joseph and Elisabeth in Bártfafürdő (Bardejovské Kúpele), Karánsebes (Caransebeș), Kassa, Királyhida (Bruckneudorf), Kismarton (Eisenstadt), Kolozsvár, Pétervárad (Petrovaradin), Pozsony, Pöstyén (Piešťany), and Temesvár. Even the First World War monuments in Kolozsvár, Nyitra (Nitra), Ojtozi-szoros (Oituz Pass), Székelyudvarhely, and Trencsén (Trenčín), as well as memorial sites dedicated to Ferenc II Rákóczi and the Kuruc in Breznóbánya (Brezno), Dolha (Dlhé), Érsekújvár (Nové Zámky), Marosvásárhely, Nagyenyed (Aiud), Zólyom (Zvolen), and Zombor (Sombor) were not spared.

A significant number of other monuments dedicated to other great figures in Hungarian history also disappeared, such as those to Saint Stephen in Őrszállás (Stanišić), Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare), and Palánka (Bačka Palanka); Saint László in Nagyvárad; King Matthias in Kolozsvár and Sajógömör (Gemer); György II Rákóczi in Kolozsmonostor (Mănăștur); Miklós Bercsényi in Ungvár (Uzhhorod); Miklós Wesselényi in Kolozsvár and Zilah (Zalău); and Albert Apponyi and Imre Szalay in Marosvásárhely.

Even monuments primarily dedicated to the important role a certain figure played in the cultural life of a particular community were banished, such as those dedicated to Gergely Csiky in Arad; Ágoston Trefort in Buziásfürdő (Buziaș); Ferenc Dávid in Déva (Deva); Ferenc (Franz) Liszt in Doborján (Raiding); Ferenc Gyulai and Miklós Jósika in Kolozsvár; Márton Lendvay in Nagybánya (Baia Mare); Ede Szigligeti in Nagyvárad; and Ferenc Kölcsey in Szatmárnémeti. The creators of these monuments included some of the most renowned Hungarian sculptors of the time, including János Fadrusz, Barnabás Holló, János Horvay, Adolf Huszár, Gyula Jankovits, Ede Kallós, Miklós Köllő, Ede Margó, Béla Radnai, József Róna, Ferenc Sidló, Alajos Stróbl, and György Zala

The fate of individual monuments

Near Baróth (Baraolt), a memorial column designed by István Prázsmári in honor of the 1848-49 revolution and the War of Independence was dedicated in September 1901. Following the border changes after the First World War, all its inscriptions and decorations were effaced, and the column itself eventually toppled in 1934 by order of the prefect of Háromszék. The column was partially restored after the Second Vienna Award, only to be vandalized once more in 1949 and demolished in 1953. By November 1973, however, everything was ready for its reconstruction, only for it to be torn down again at the request of the local communist party committee.

In Buziásfürdő, a bust of the former minister of religion and education, Ágoston Trefort, designed by Adolf Huszár, was destroyed in the summer of 1919. In its place, the Romanians dedicated a statue to their most famous national poet, Mihai Eminescu. On May 26, 2001, a new bronze bust of the eminent minister of religion and education, designed by Péter Jecza, was erected on the grounds of the local Reformed Church center.

In Karánsebes, a white marble statue of Queen Elisabeth of Hungary, dedicated on May 6, 1918, designed by János Horvay (who received the noble appellation Mecsekalkai for this work), was vandalized after the border changes. The effaced statue, however, remained in place until 1944-45, when it was removed by advancing Soviet troops. Fragments of the statue were discovered in 2000, and its restoration is currently planned by the Caransebeş County Museum of Ethnography and the Border Regiment.

In Kolozsvár, a wooden military statue, the Guardian of the Carpathians, erected in August 1915 and designed by Ferenc Szeszák, was toppled by the invading Romanians at the end of December 1918. There were similar wooden statues erected in many places at the time, with the proceeds derived from nails driven into the statues by donors used to support the widows and orphans of soldiers who had gone to war. A replica of Szeszák’s work, sculpted by János Béres Horváth, was dedicated on November 17, 2002, in the Szalajka Valley.

In Lőcse (Levoča), local inhabitants made two efforts to prevent the removal of the Honvéd Monument (a monument commemorating Hungarian soldiers), which had been dedicated on May 21, 1876. Nevertheless, this work by József Faragó was boarded up and then taken down on the night of August 11/12, 1919. Local inhabitants protested in front of the statue the next day, during which a Slovak maidservant was killed by police. In the following days, a general strike was organized in the city with shops and offices closed. The broken statue, meanwhile, was stored in the city archives. The pedestal – as was the case in Košice – was adorned with a stone flowerpot, which was subsequently replaced by a statue of the Slovak revolutionary Ľudovít Štúr in October 1949, after the Second World War. The remains of the monument were recently discovered, and the original statue head was unveiled in 2019.

In Magyarittabé (Novi Itebej), a bust of Lajos Kossuth, the work of János Horvay, who sculpted Kossuth some twenty times, was dedicated in front of the Reformed Church on May 7, 1904. However, the invading Serbs knocked down the bust at the end of 1918. It was thereupon stored at the local Reformed Church and then re-erected in 1941 following the Hungarian annexation of the region in December of that year. The bust, however, was stolen on the night of April 3, 2016, but as the result of a collection spanning the entire Carpathian Basin, it was recast in the model of the Kossuth statue in Soltvadkert, also made by Horvay. The completed work was finally dedicated on March 15, 2016.

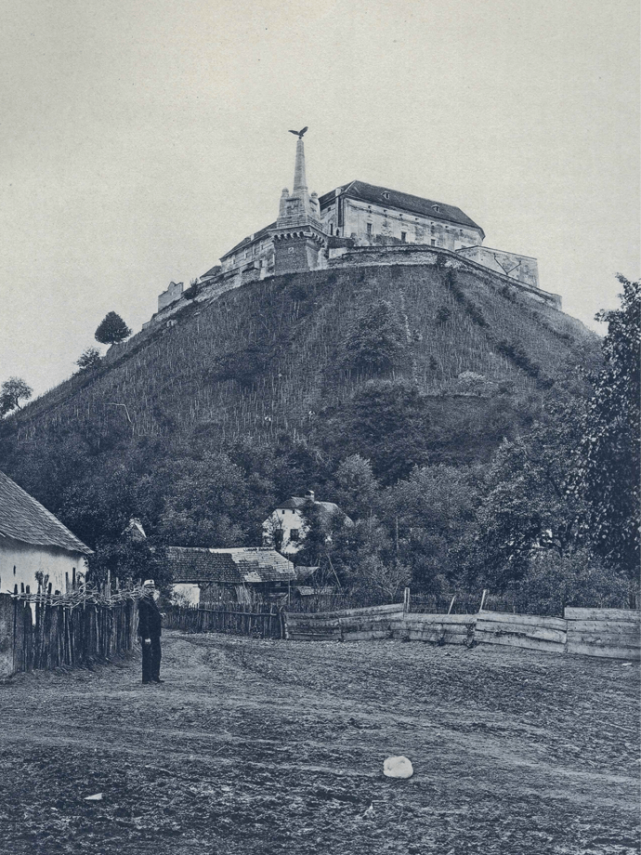

The Millennium Monument in Munkács, designed by Gyula Bezerédy and dedicated on July 19, 1896, was crowned with a mythic turul bird with a 4.5-meter wingspan. In December 1924, a scaffold was thrown up, the turul taken down, and the obelisk dismantled. The bird itself was cut into pieces in 1944-45, and the metal was recast into five-pointed stars to adorn Soviet monuments. The monument was re-erected in 2008, with a new, larger turul, created by the Uzhhorod sculptor Mihajlo Beleny, and dedicated on April 18 of that year. On October 13, 2022, however, local Ukrainian authorities removed the turul once more and replaced it with a Ukrainian trident.

In Marosvásárhely, three statues of Kossuth, József Bem, and Ferenc II Rákóczi, designed by Miklós Köllő, Adolf Huszár, and Károly Székely, respectively, were simultaneously toppled by “unknown perpetrators” on March 28, 1919. The first was replaced by an Orthodox cathedral, while the second was donated by the Romanian government to Poland in November 1928 but never arrived, having disappeared in Bucharest. As for the statue of Rákóczi, a statue of the Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi by sculptor László Hunyadi has stood in its place since December 16, 2000.

In Nagybecskerek (Zrenjanin), a life-sized bronze statue of General Ernő Kiss, dedicated on May 27, 1906, was blown up on July 26, 1919, and replaced by an equestrian statue of King Peter I of Serbia. In 2005, the statue’s head – sculpted by Béla Radnai– was found in the storage room of the local museum. Based on this, a new version of the statue was recast and erected on the grounds of St. Augustine’s Church in the village of Elemér (Elemir), in whose crypt the martyr, one of 13 Hungarian generals executed in 1849, was buried.

In Nagyenyed, a student memorial built by József Klösz and Mihály Bertha and dedicated on May 10, 1896, was damaged in late 1918. The memorial was erected in honor of 30 students of the Nagyenyed Reformed College who fell during Rákóczi’s War of Independence (1703–11), a theme that also inspired Hungarian writer Mór Jókai’s story “A nagyenyedi két fűzfa” [The two willows of Nagyenyed]. Despite the damage, the memorial’s altar stone was saved and stored in the college’s antiquities section. Restoration work on the memorial was carried out in 1972 and again in 2010, when the area around the memorial was also refurbished.

In Nagyvárad, a bust of the Hungarian dramatist Ede Szigligeti, dedicated on December 15, 1912, and installed in front of the theater named after him, was banished to a more distant park in 1921. Created by the Hungarian sculptor Ede Margó, the bust was not tolerated for long in its new location and was eventually dismantled by the Romanian authorities in 1937. The bust’s original location became home to a statue of Queen Mary of Romania, only to be replaced by the original bust of Szigligeti in February 1941.

In the Ojtuz (Oituz) Pass, a First World War relief dedicated to the 18th Hungarian Infantry Regiment of Sopron was removed by Romanian authorities in 1919. A replica was first erected in Sopron in 1934 and then on the grounds of the Roman Catholic Church in Ojtoztelep (Oituz) in 2007.

In Pozsony, a statue of Sándor Petőfi dedicated on September 8, 1911, was boarded up by the Czechoslovak authorities in November 1921 and thereupon confined to the stables of the Grassalkovich Palace. A work of the Hungarian sculptor Béla Radnai, the sculpture was installed on the other side of the Danube in the 1950s before being placed in the Medical Garden following its restoration in 2003.

In Rozsnyó (Rožňava), a statue of Kossuth dedicated on the main square on May 26, 1907, was pulled down off its pedestal by drunken Czech legionnaires with a rope on the night of June 18, 1919. This work of the Hungarian sculptor József Róna, however, was rededicated in 1938, shortly after the First Vienna Award. The statue was dismantled again in 1945, only to be re-erected once more in the square next to the Folk Art Museum on January 1, 2001.

The statue of Prince István Bocskai by sculptor Géza Horváth, dedicated in Nyárádszereda (Miercurea Nirajului) on July 17, 1906. In early 1920, Romanian gendarmes in the village began using the statue for target practice before finally knocking it down. In 1924, the statue was moved to the local church and then stored in the theological seminary in Kolozsvár between 1933 and 1940. It was returned to Nyárádszereda on November 24, 1940, following the Second Vienna Award. It was removed again in 1944 and stored in the local church once more before being erected on a pedestal before the church in 1976. It was finally returned to its original location in 1997.

In Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe), a military memorial by the sculptor Antal Gerenday was dedicated in the main square of the town on October 11, 1874. The corresponding obelisk was demolished in 1934 but restored to its former glory in 1940. The obelisk, which was toppled again in the fall of 1944, was restored in 1947, but with the inscription and coat of arms effaced. It was finally restored to its original appearance in March 2018.

In Szatmárnémeti, a bust of the Hungarian poet Ferenc Kölcsey, sculpted by Antal Gerenday, was dedicated on September 25, 1864, and later moved to the ornamental garden in front of the Láncos (Reformed) Church. On the night of December 20/21, 1920, however, this monument was toppled as well, and the mutilated bust – whose head had been sawed off in August 1934 – was erected in the church cemetery and then positioned on the other side of the church in 1942. The bust was permanently removed in 1947, and its remains stored in the Satu Mare County Museum. In its place, a new Kölcsey bust sculpted by Pál Sándor Lakatos was dedicated in 1991.

The Millennium Monument in Zimony (Zemun), the work of József Róna (stone statues) and Gyula Bezerédi (turul bird), dedicated on September 20, 1896. On the night before Pentecost, in 1924, Serbian youths removed the turul bird from atop the tower, tore down the central coat of arms, toppled the figure of Hungária, and effaced the inscriptions. The architectural part of the monument remains standing today, functioning as a lookout platform and a viewing gallery.

In Székelyudvarhely (Odorheiu Secuiesc), the Iron Szekler Soldier (Vasszékely), erected in 1917 in honor of the 82nd Székely Infantry Regiment, was pulled down and destroyed by the Romanians on February 9, 1919. The monument, designed by István Erdélyi, was restored by sculptor János Szabó on March 15, 2000. The same site was the home of a millennium monument, a masterwork by the sculptor Nándor Hargita (Scheffler), which was dedicated on June 26, 1897. It too was toppled by the Romanian authorities in 1919. The monument was restored on May 25, 2008, with the addition of a turul bird designed by Walter Zavaczki positioned at the apex.

In Törökbecse (Novi Bečej), the fate of a bronze statue of the martyr Count Károly Leiningen-Westerburg, one of 13 Hungarian generals executed in 1849, presents an extremely interesting case. A work by the sculptor Béla Radnai, the statue was removed from its pedestal in 1920 and stored in various places until it was found intact in 1954 and donated to the local football team, who sold it as scrap to purchase sports equipment. In October 2009, as modest reparation, a new statue of Leiningen-Westerburg, made by Hungarian sculptor Sándor Győrfi, was erected in the garden of the St. Clare of Assisi parish in the town.

Also in Törökbecse, on the market square, a monument of liberty was erected in memory of the heroes of 1848-49. The eight-meter-high memorial column was designed by Géza Bánlaki and constructed by János Fischer, a stone carver from Szeged. The obelisk was crowned with baroque ornamentation comprising a turul with wings outspread holding Attila’s sword in its beak. The obelisk was torn down at the end of 1918, and the turul tossed into the Tisza River. More recently, however, the turul was rediscovered, buried under a two-meter layer of silt, and its extraction and restoration are planned with public donations.

In Trencsén, a relief depicting Hunnia, the allegorical personification of Hungary, commemorating those who had fallen in the First World War, was carved into the rock at the base of the eponymous castle. Completed on October 4, 1916, it was removed by the Slovaks at the end of 1918 and replaced by a relief carving of the Czech Hussite leader Jan Jiskra in 1921.

In Zólyom, a bust of Ferenc II Rákóczi located on the main square and dedicated on June 2, 1907, could not escape its fate. In 1920, this work of the sculptor Ede Mayer was moved to a farm building in the courtyard of the town hall and subsequently made its way to the chapel of Zólyom Castle, where it was found in 1943. Around 1967, it was taken to Fülek (Fiľakovo), whence it was removed to the prince’s birthplace in Borsi (Borša). On May 31, 1969, the bronze bust was rededicated in Borsi, where it was toppled once more on February 28, 2013, only to be restored a few months later.

The Monument of Liberty in Arad, the work of Adolf Huszár and György Zala, honoring the 13 Hungarian generals executed in 1949, was dedicated on October 6, 1880. Following the dismantling and boarding up of the Kossuth statue in Arad in 1921, the Romanian government ordered the Monument of Liberty to be removed on May 30, 1925. The monument was taken down in July 1925, and its components first placed in the former city stables, then stored in Arad Castle, and finally moved to the courtyard of the Minorite monastery in 1999. The monument was subsequently restored and rededicated on April 25, 2005, not far from its original location, in the Romanian-Hungarian Reconciliation Park. The monument stands opposite a triumphal arch dedicated to the Romanian revolutionaries of 1848.

In Zombor, a statue of General József Schweidel, another of the 13 generals executed in 1849, was dedicated on May 18, 1905. This work, the creation of the sculptor Lajos Mátrai, was demolished by Serbian troops in 1918. It would not be until March 17, 2017, that the martyred general would be commemorated in his hometown once more. On that date, a new bust of General József Schweidel, the work of the sculptor Péter Mrákovits, was unveiled in the courtyard of the Hungarian Civic Casino in Zombor.

These particular cases have been cited in order to convey the history of Hungarian memorial sites beyond the present-day borders of the country and their often tumultuous fate after the fall of 1918. Unfortunately, they can be augmented with numerous other examples. The new authorities, in most cases, did not tolerate their existence, so they were generally removed and often replaced with other monuments erected to honor the new “state-building nation.” However, thanks to the political changes after 1990 and the ensuing Hungarian political and civil initiatives, some of these memorials have been restored – sometimes in the same locality involving the same themes and personalities, and sometimes in a different place and in a different form. This development is certainly grounds for optimism – the past cannot be as easily erased as was thought within the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy after the fall of 1918.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)