“They extract salt from the mines with a pickaxe,” wrote the medieval prelate Antal Verancsics in his mid-sixteenth-century Latin poem about Transylvania, and with this he captured what was perhaps the most characteristic feature of this eastern part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Apart from diplomats and the adventurous young men who accompanied them, the foreign travelers who wrote travelogues or geographical descriptions of Transylvania in this century were mostly drawn there by the mines full of fabulous treasures.

Some of the “observers” who came to Transylvania for political or economic purposes exhibited a particularly hostile attitude towards the region and its rulers, the Szapolyai family. The highly learned Sigismund Herberstein, who traveled across Hungary thirty times between 1518 and 1551 as a Habsburg diplomat, had harsh words for the turbulent local conditions. Perhaps the most interesting of his impressions of Transylvania was that he believed that the Szeklers “spoke the ancient, original Hungarian language while other Hungarians had peppered their speech with words derived from Latin and the languages spoken by neighboring peoples.” Hans Dernschwam, who, as an agent of the Fugger-Thurzó mining company toured the Transylvanian salt mines, referred to János Zsigmond Szapolyai (II) as illegitimate, adding that despite this, he even dared call himself king, as is clearly evident on the gold and silver coins he minted.

Some of the foreigners who came to Transylvania during the later Báthory period, however, would have a more favorable opinion of the country. Interest in the salt and gold mines grew in the latter half of the century and encouraged many Western European merchants to try their luck in the remote but wealthy land. Thanks to its learned princes, Transylvania was receptive to the arrival of Italian, Polish, and French humanists, royal envoys, and even soldiers of fortune, some of whom conveyed their impressions of Transylvania in lengthy descriptions while others were confined to brief letters. We now offer readers a sampling of these.

One particularly valuable – albeit rather one-sided – travelogue of Transylvania was compiled in the early 16th century by Hans Dernschwam, who was originally from Bohemia but later settled in the Kingdom of Hungary. The future Fugger family mining expert began studying at the University of Vienna in 1507 at just 14 years of age, alongside two of his brothers. 1509-10, however, saw him transfer to the University of Leipzig, where he earned a baccalaureate degree, although he did not pursue his studies further. After a few years in Rome, Dernschwam arrived in Buda, whence he and his family settled in various Hungarian mining towns. Through his university classmate, the Moravian-born Stephan Taurinus (Stephan Stieröchsel), he came into contact with Jacob Fugger and, through him, with the Thurzó family of Bethlenfalva, (now Betlanovce). Dernschwam’s connection with the Fugger–Thurzó mining company began sometime in the early 1510s and would last the rest of his life.

Transylvanian salt mines of the late medieval period

Dernschwam was employed by the Thurzós in the mining town of Besztercebánya (now Banská Bystrica), where he gained extensive experience in mining and minting. By 1525, he had already earned a high place in the Fugger–Thurzó mining company. He gained especial notoriety, also in 1525, when he evacuated the company’s documents from Besztercebánya to Cracow shortly before the arrival of King Louis II of Hungary’s agents, sent to the mining town to confiscate the company papers. After the Thurzós withdrew from the lower-Hungarian mining company in 1526, Dernschwarm continued to be engaged exclusively as an agent for the Fuggers. When Ferdinand I, king of Bohemia and Hungary, borrowed 40,000 forints from the Fugger bank in Augsburg in 1528, he ceded them the income from the Transylvanian salt mines as collateral. The banking family’s first task was to dispatch a highly educated, loyal man to Transylvania to assess the state of the salt mines there.

Dernschwam set off from Buda for Transylvania on July 4, 1528, with two wagons. He arrived in Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia) ten days later, having passed through Szolnok, Gyula, and the Fekete-Körös valley. The traveling party included Ferdinand’s envoys to Transylvania, Leonhard Nogarola, and the Saxon István Pemfflinger. In Gyulafehérvár, Dernschwam immediately sought out Miklós Gerendi, a Transylvanian bishop and Ferdinand I’s treasurer, as well as the first president of the newly established Hungarian Chamber. He began inspecting the salt mines and almost immediately appointed new people – German employees of the House of Fugger – to head the salt chambers. Dernschwam’s contacts in Transylvania were primarily limited to the pro-Habsburg aristocrats, with whom he tried everything possible to keep Transylvania on Ferdinand’s side. While inspecting the salt chambers, Dernschwam sent one of his servants to Nagyszeben (now Sibiu) to obtain Hungarian clothes because, as he was now working mostly with Hungarians, he wanted to dress like them as well.

Dernschwam carried out his task to the letter, having already compiled his report on the state of the Transylvanian salt mines and sent it to the Fugger representative in Buda, Jacob Hunli, in August 1528. His report paints a generally depressing picture of the Transylvanian salt mines: the mines were literally bare, lacking the proper equipment, and the required tools were nowhere to be found. Nothing could be obtained in the marketplace even if you offered double the going rate. The salt mines in Torda (now Turda), for example, were in need of draught horses, bridles, tallow, towing ropes, and various iron and steel implements to establish a more efficient operation. However, trade routes had been disrupted by the continuing conflict with the Turks: “You should know that there are no open roads across Transylvania now; soldiers are encamped everywhere, so no peasants are coming this way.” According to Dernschwam’s assessment, the most valuable, most excellent, solid white salt can be obtained from the Torda mines, but he noted that there was a lot of waste and much salt debris resulting from the operation.

His notes describing the various salt mines give us an idea of how mining was done at that time: “There are now two mines in operation here [Torda]. They are located close to one another, about thirty paces apart, and each mine has three shafts arranged in a triangular configuration. […] In the larger mine, two draught horses haul up a covered transport cart, which is used to bring up to the surface each day both the salt extracted by the salt cutters and the waste, i.e., the salt debris and water. In another shaft, the salt miners descend on ladders. And in the third, a fire in a large copper cauldron is hoisted down into the mine to deal with the stench.” In the area around Torda, local salt miners had tried to open up new shafts prior to Dernschwam’s arrival, but these had already flooded at a depth of one ladder, with the water rising to a man’s height. However, the salt cutters related that with six horses, they could remove the water from these makeshift shafts in three or four weeks, but unfortunately, they had neither the horses nor the equipment to do so.

Dernschwam noted that the mined salt was carelessly stored at the mine, with large quantities of it lying in heaps in the open air, where it was often ruined by the rain. He thus suggested that warehouses, sheds, or barns be erected to protect the salt blocks. Derschwam also listed the various way stations of the transport waterway starting on the Aranyos River and continuing along the Maros, including the salt-storage sites and stations as far as Szeged. The other salt transport route, running from Dés (Dej), along the Szamos and Tisza rivers into the Hungarian interior, was also deemed useful and feasible for exporting salt blocks from Transylvania. For his associates, it was not the salt sold in Transylvania but the salt that could be sold outside it that could bring in the most revenue. As for the staff he appointed, he noted that “almost all of them know three or four languages spoken in the country. They speak German, Hungarian, and Romanian, and one also speaks Polish.”

While he diligently inspected the salt mines, he perused with great interest the Roman-era stones that were still abundant at that time. His good friend, the humanist-educated Taurinus, may have encouraged him to take note of their inscriptions, but his years in Rome may have also sparked his interest. Dernschwam’s travelogue provides a drily stark assessment of salt-mining conditions of that time. The author exhibited little sympathy for Hungarians, nor was he sparing with critical remarks in his later notes on Hungarian conditions and actors in the 1530s and 1540s.

A French traveler at the royal court

By the last third of the 16th century, Transylvania already presented a radically changed image for the foreign observer. Pierre Lescalopier, a French diplomat traveling from Constantinople to the court of István Báthory in Transylvania, paints a picture of a cultured and bustling court life and a flourishing country. The young French nobleman, who also spoke excellent Latin, was led to Transylvania by chance and a planned French-Transylvanian royal marriage.

Lescalopier, born of a noble Italian family that had become extremely wealthy and distinguished by the 16th century, was born in Paris around 1550. He was studying law at the University of Padua when his curiosity led him to the mysterious Balkan lands, and he arrived in the Ottoman capital in 1574 with a letter of recommendation from Venice in his pocket. He immediately paid his respects to Bishop Noailles, the French ambassador to the Ottoman court at the time, who promptly assigned the enthusiastic young man a diplomatic commission. He was to deliver a message to the prince of Transylvania, István Báthory, on behalf of his king. He was on his way there from the Ottoman capital with the Transylvania envoy when he arrived in Gyulafehérvár on July 2, 1574, after a month on the road.

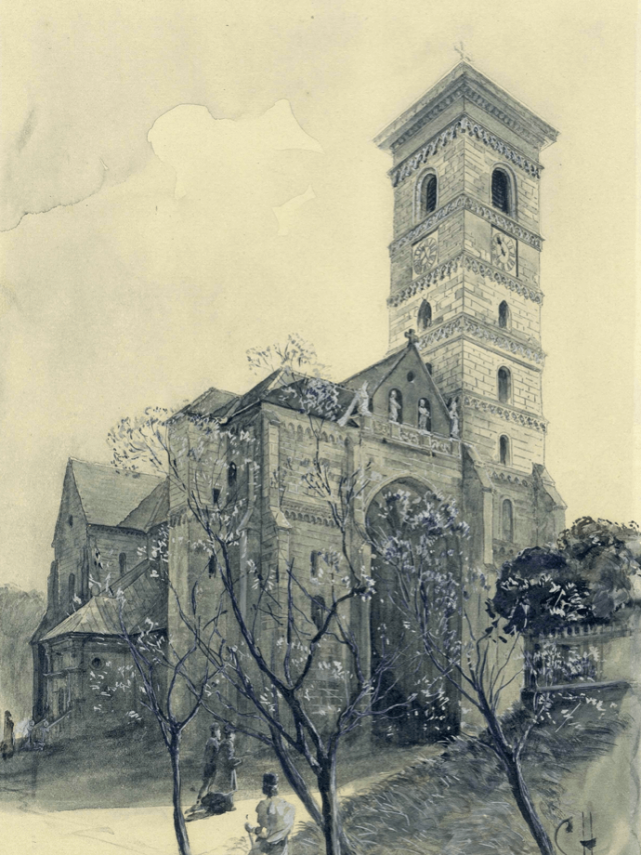

St. Michael’s Cathedral in Gyulafehérvár

Since the planned marriage of the Transylvanian prince and the French beauty known as La Belle Châteauneuf, Renée de Rieux (1550-1586), soon fell apart both for political and personal reasons (the young woman, as a former lover of King Henry III, was not exactly famous for her virtues), our French friend was only able to stay in Transylvania for three weeks. Lescalopier, however, kept an invaluable, almost daily record of his journey, which took him through the Balkans to Transylvania and from there through Hungary and the Austrian provinces to Venice. His descriptions of the journey to Transylvania – both through the Balkans and of Transylvania itself – are more detailed and thorough than those of the journey home, as he had to depart suddenly and hastily. Lescalopiers’ travel notes, some 66 pages in all, were deposited in the library of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Montpellier, where they are kept to this day.

Lescalopier’s accounts of Transylvania are an authentic resource for the later reader. On the one hand, they provide behind-the-scenes insight into the princely marriage policy towards France, and on the other hand, they bear witness to the contemporary Transylvanian economy, mining operations, and social conditions. Lescalopier spoke glowingly of the most influential political figures and of the prince himself and greatly appreciated the warm hospitality he received.

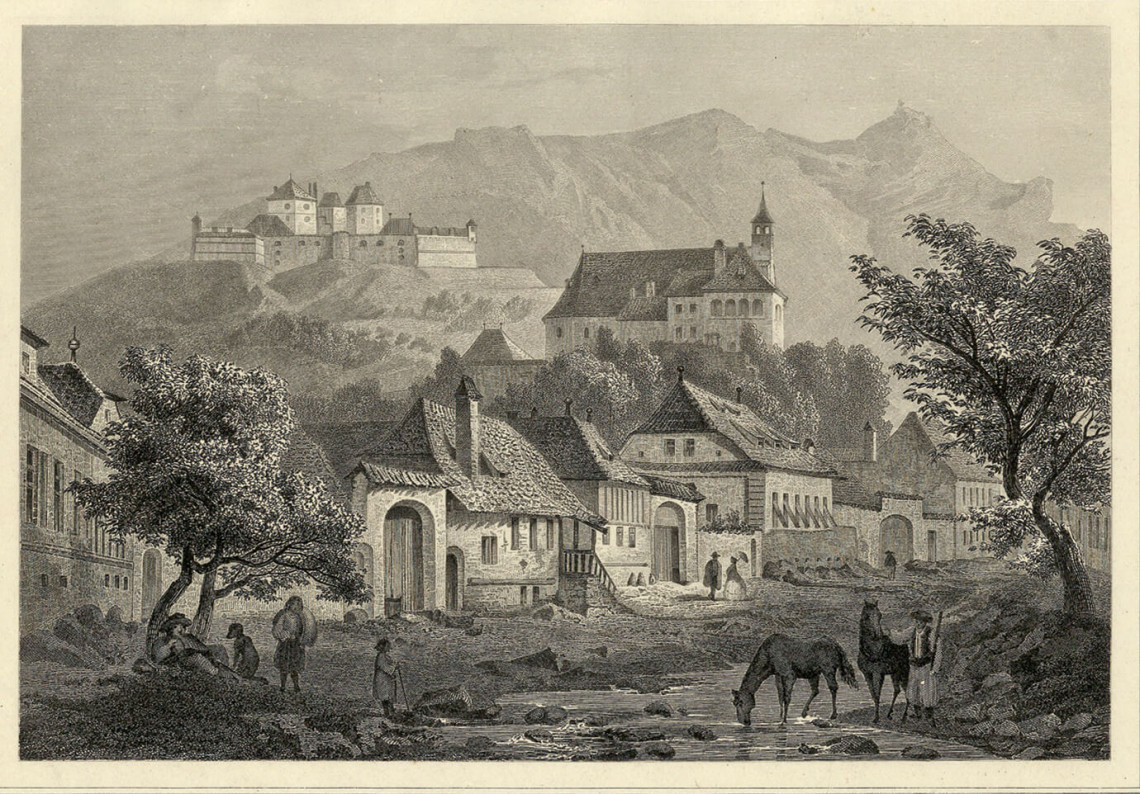

The French traveler arrived in Brassó (now Brasov), the first large Transylvanian town, on June 24, 1574, which he saw as particularly beautiful and which elicited direct comparisons to Mantua. He praised its beautiful churches, strong walls, and well-paved streets and found the population extremely friendly. He was pleased to learn he was able to converse with the chief magistrate – albeit in rudimentary Latin, which he could speak with some ease – which was a great pleasure for him, as he had been unable to converse at length in any of the languages he knew when traveling through the Balkans. The Brassó magistrate was well informed of the planned marriage between Báthory and the alleged niece of the French king – alleged, for the young lady was in fact not his niece – and as he told the envoy, he had been explicitly instructed to be courteous to his guests. In fact, Báthory made one of his secretaries available as a travel guide.

After Brassó, the Frenchman’s party passed through Hungarian, Saxon, and Romanian villages and forested countryside, arriving first in Nagyszeben and then Szászsebes, before finally descending upon Gyulafehérvár on July 2, where they rested: “The castle is large and strong, and next to it is a bustling, densely populated market town. Neither Germans nor Vlachs (Romanians) live here – everyone speaks the land’s original language, Hungarian, as Transylvania was formerly a province of Hungary. But this flourishing, beautiful Christian kingdom collapsed due to Austrian usurpation, which forced the mother of the last Hungarian king to appeal for Turkish assistance.”

He then related how the Turkish sultan left only this one province in the hands of the king’s mother, Isabella, and her infant son, the future John II of Hungary, and from this arose the Principality of Transylvania. He noted that Gyulafehérvár became the capital of the province because of its healthy air and the good fields surrounding it and opined it must have been a large town in the past because many Roman wooden remains and inscriptions had been found there.

Prince István Báthory received the French envoy in his palace on July 3, whereupon they had a lengthy conversation in Latin. While conversing with the prince, he was surprised to recognize in the prince’s nephew, his namesake István Báthory, his former student friend from Padua days, with whom he exchanged greetings in Italian. He also had lengthy conversations in Italian and French with a number of government officials, including Chancellor Márton Berzeviczy and court physician and princely councillor Dr. Blandrata.

Lescalopier otherwise had an extremely pleasant time at the princely court. They hunted a lot, rode horses, and had festive dinners in honor of the betrothed, although Lescalopier could not provide the prince a detailed description of either the personality or the beauty of the young woman the prince proposed to marry. He excused himself by saying that he had left France three years previously and was not exactly familiar with the conditions at home. Nevertheless, the mystery surrounding the mysterious woman Báthory proposed to be his wife was dispelled when an Italian lute singer, who had secretly spread word that the young woman was not a true relative of the French king and that her reputation was badly tarnished, was brought before the prince.

A view of Brassó with the old town and castle

However, this was not the only reason why Dr. Blandrata, for one, felt the marriage plans were doomed to failure. Rumors of the political turmoil in France following the death of Charles IX had also reached Transylvania, and it was even known that the deceased king’s brother Henry had vacated the Polish throne that same year and returned to his native France to become king at home. There was also talk that the King of Navarre and the Duke of Alençon were preparing to cast off royal authority. In the midst of such internal political uncertainty, it would make no sense to enter into a marriage alliance with the French, the prince thought. This general opinion of the court was communicated to the rather uninformed Lescalopier. A few days later, on July 20, the prince made a statement to this effect during a personal audience, expressly ruling out the possibility of the proposed marriage, about which he wrote a letter to the French queen, Catherine de Medici. The French delegation, led by Thomas Le Normand, was ceremoniously dismissed.

During these discussions, the members of the delegation had the opportunity to spend several days visiting the gold and mercury mines of Zalatna, now Zlatna, and thus Lescalopier was able to provide a thorough description of these mines and even of the mining process itself. Returning to Gyulafehérvár, he saw a relief carved into St. George’s Gate, depicting a she-wolf nursing two infant boys. He also saw other Roman-era stones and recorded the inscriptions in his notes.

The day after the royal dismissal, the French delegation set off from Gyulafehérvár, visiting Enyed (Aiud) and Torda along the way. Regarding Torda, Lescalopier noted that the remains of an ancient city were found here, with inscriptions on Roman-era stone fragments, and he indicated that the salt found in the nearby mines was so pure it was fit for human consumption without any preparation. The delegation arrived in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca), on July 23, which Lescalopier described as “a beautiful, fortified town with painted facades. Its inhabitants are a mixture of Germans and Hungarians, having been solely German a few years ago.” With respect to Kolozsvár, our traveler explained that the Transylvanian Saxon towns kept their gates firmly shut, not even admitting Hungarians for marriage. Anyone who married a Saxon girl would have to take her back to his own village, as he could not move in with the Saxons. “At present, Kolozsvár does not number among these towns, as eight or nine years ago they stopped guarding the town gates. They valued the country’s freedom more and wanted to live like Hungarians in every way. The other six towns continue to live under their old governments and councils. The prince swears an oath to preserve their freedoms and provide them justice. Everything is decided in the prince’s name, but they do not allow a party of more than three hundred persons within their walls.”

Leaving Kolozsvár, they stayed in Monostor (now Mănăștur), where some Italian tenant farmers served them some truly excellent red wine. Over dinner, presumably after drinking several bottles of wine, they learned that the red wine was so red because it was made from cherry juice, as red grapes did not grow in the area. All in all, Lescalopier spoke highly of the Transylvania of his time, saying that the land was rich in all kinds of goods. He found the princely capital and its court tidy and pleasing, the court etiquette impeccable, and the provisioning truly elegant and attentive. The French delegation left Transylvania on July 24, 1574, and continued its journey through the Kingdom of Hungary.

Lescalopier on the mining of gold and mercury

“The prince’s nephew showed me Zalatna, where gold and mercury mines are located, which are leased by Jacomo Grisoni of Venice and Fausto Guai of Rome, the latter having been brought up in Paris until he was eighteen […]

On July 5 [1574], we visited the gold mine, which extends very deep into the bowels of the earth under a high mountain. The rock extracted here is first burned by the miners, as is usually done with gypsum, and then ground in a watermill. For this, the burned rock is placed in a wooden trough one foot wide [approx. 30 cm.] and twice three fathoms long [approx. twice 9.36 m.]. Here it is crushed by a few thick piles that rise and fall in succession, crushing the stone to the size of pebbles. The sediment and crushed rock drift slowly down the trough of flowing water, and once leaving it are spread out on rough canvas stretched over a large basin with gently sloping boards. The gold adheres to the canvas, and what does not falls into the basin along with the water flowing over top, and which drains out the bottom. Every twenty-four hours, the miners twice remove the canvases and wash them out in another basin. The sediment or wet sludge left in the basin is then spread out on a large wooden tray. This is shaken until the gold collects on one side while the excess sediment remains on the other side of the tray.

On [July] 6, we visited a mercury mine. On a mountain half a mile above sea level [approx. 1350-1450 m], one can descend into the mines through round pits that resemble wells. From them, yellow-reddish earth is brought to the surface in narrow-mouthed clay pots. A small amount of charcoal is placed in the mouth of the clay pot, which is then sealed with a wooden stopper. Several pots, similarly prepared, are placed mouth downwards, covered with damp earth, and a large fire placed over them on all four sides. Once the fire goes out, after four or five hours, and the pots have cooled, the latter are removed and opened. It is immediately seen that the earth in the pots has been liquified by the action of the charcoal placed at the mouth of vessels and that the mercury is clearly in motion. Around five hundred pots are prepared in this way and placed next to each other at each fire.”

Jacques Bongars (1554–1612)

Jacques Bongars on Transylvania

A decade after Lescalopier’s journey, in 1584, another French traveler, Jacques Bongars (1554–1612) of Orléans, recorded his own experiences. Bongars, starting from Vienna, also made his way to Constantinople, this time from the north, passing through Hungary. His travel diary is not particularly interesting, usually devoting no more than one or two sentences for each town. As for Transylvania as a whole, he summarized it as follows: “Transylvania is a hilly region abundant in grain and wine and surrounded on all sides by mountains resembling battlements. All kinds of ore are also found in abundance. The rivers also carry gold, which is collected by people designated for this purpose. Transylvania pays the Turks a tribute of 14,000 thalers; otherwise it is free. Some years ago, for example, a Transylvanian offered 100,000 thalers for the principality, but the chargé d’affaires in Constantinople objected to this, as Transylvania was not subject to the Turks but was a country under their protection.”

Some writers who passed through Hungary in the 16th century and penned travel diaries also described the country as a whole. Although by the last third of the century the country’s fragmentation had become permanent and apparent to most foreign travelers, it is interesting to note that the Frenchman Jacques Esprinchard (1573-1604), who was passing through in 1597, had the following view of Hungary: “Hungary is separated from Poland in the north by the Carpathian Mountains, which separate it from both Poland and Moldavia. It is bordered to the south by the Sava River, to the west by Austria and Styria, and to the east by the river Olt, which includes Transylvania.”

This late 16th-century record is perhaps the last mention of the old united Hungary made by a foreign traveler. In the following century, this view would disappear from travel accounts, and the parts of the once united Kingdom of Hungary were recorded as separate lands by passing diplomats, envoys, or craftsmen.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)