“A mountain-chain, pierced through from base to summit – a gorge four miles in length, walled in by lofty precipices; between their dizzy heights the giant stream of the Old World, the Danube. Did the pressure of this mass of water force a passage for itself, or was the rock riven by subterranean fire? Did Neptune or Vulcan, or both together, execute this supernatural work, which the iron-clad hand of man scarce can emulate in these days of competition with divine achievements?” It was with such enthusiasm that the Hungarian novelist Mór Jókai wrote about the Iron Gate in his novel Az arany ember, or “The Golden Man” (translated as Timar’s Two Worlds). For travelers venturing there, this massive, towering gorge remains a breathtaking sight, and its history is no less stirring.

The Iron Gate holds a prominent place in Hungarian public sentiment. Both its spectacular panorama and its setting have stirred people’s imagination. Since ancient times, the southern confines of the Carpathian Basin have skirted the Carpathian Mountains (including their westernmost part, the Banat Mountains) before running south to the Balkan mountain ranges, or more precisely, the Serbian Carpathians (Srpski Karpati). Moreover, since the 19th century, this has also been the meeting place of numerous cultures – Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian, Turkish, and Bulgarian. However, before we delve into the twists and turns of the Iron Gate’s history, it is worth clarifying some of the geographical aspects of this locale in a few words.

– a 122 km long

path carved into the impressive, vertical limestone cliffs

Neptune’s legacy

The term “Iron Gate” is used in two senses. More broadly (and more imprecisely), it refers to the entire, roughly 130-kilometer stretch of the Danube River between Golubac (Galambóc) and Drobeta-Turnu Severin (Szörényvár). More specifically, it refers to one of three exceptional narrowings on this section of the Danube, just east of the Great and Small Kazan gorges, between the towns of Orșova (Orsova) and Drobeta-Turnu Severin, and where a massive hydroelectric dam stands today. Due to the presence of the latter, we cannot even imagine what the old Iron Gate must have looked like when considering the river’s present state.

The original water level was some 30 meters lower, and the river itself was dotted with rocks and rapids, especially at low water levels. The formation of this spectacular river valley is also unusual as the Danube flows through lowlands both above and below this point; thus, it has already progressed beyond the steep, ravine-cutting mountainous section of its course. As a consequence, this river valley constitutes an anomalous and discordant feature, similar to but much more dramatic than the Danube bend, north of Budapest.

The question naturally arises, how was such an impressive stretch of river created? Some 20 million years ago, a narrow strait similar to today’s Bosphorus connected the then-emerging Carpathian Basin with an inlet of a sea, which covered the region of present-day Romania and Bulgaria. This strait was “taken over” by the Danube after the aforementioned branch of the sea retreated. Although the two bordering mountain ridges continued to rise, the Danube had already “chosen” this route for itself and could not alter course; instead, the river deepened its bed in defiance of the rising heights of its surroundings. This is how the precipitously sided valley was created.

The banks of the river here are home to a wide variety of rock formations. In the narrowest sections, limestone embankments tower above the water, constricting the Danube to such a degree (170 meters across in the case of the Great Kazan Gorge) that the river is forced to accelerate and deepen its bed to almost sea level. If there is limestone, there must be caves – and indeed there are numerous caves and smaller karst depressions on both sides of the river.

From Trajan to Széchenyi

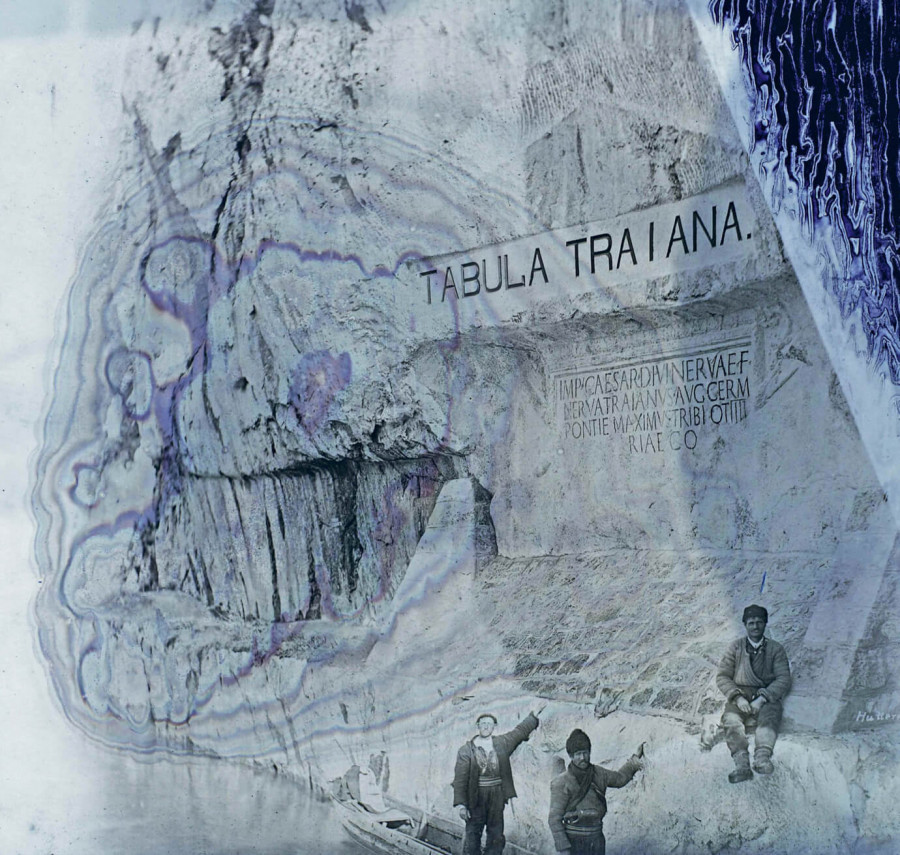

The Iron Gate has been a vital strategic point since ancient times for the peoples living in the region. The Emperor Trajan had a towpath built alongside the gorge for his first Dacian campaign after which he had the largest bridge in the ancient world constructed here in order to maintain contact with the subjugated province of Dacia. The Romans, meanwhile, had also discovered and begun to use the medicinal waters of the nearby Hercules Baths. It is no surprise then that a little further down the river, on the left bank of the Danube, near present-day Drobeta-Turnu Severin, the remaining pillar of Trajan’s Danube Bridge, considered one of the greatest engineering works of antiquity, is treated with great reverence. Trajan’s Tablet (Tabula Traiana), a memorial plaque dedicated to the great Roman emperor, remains one of the most popular photo subjects of the Iron Gate.

Many centuries later, during the Turkish onslaught, it became a key defensive position, as evidenced by the fortifications built nearby (many of which are now submerged), such as Golubac (Galambóc) – whose 1428 siege was the theme of János Arany’s ballad “Rozgonyiné,” Severin (Szörényvár) – one of János Hunyadi’s most important strongholds, and the Orșova (Orsova), Drencova (Drankóvár), and Trikule (Háromtorony) fortresses. At the same time, the Danube was so rapid, narrow, and dangerous for navigation that it could only be used for commercial purposes. Following the expulsion of the Turks, the region had almost become the equivalent of the “end of the world.”

Nevertheless, the Habsburg Empire and the declining Ottoman state eyed each other here for another century and a half, so much so that, for example, the fortresses of Old and New Orșova – the latter built by the Habsburgs in the then-modern Vauban style – changed hands several times. During the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars, it first became the property of the imperial family in 1687, only to be recaptured by the Turks in 1670. It was given back to the Habsburgs following the Peace of Passarowitz (1718) – during which time the then heir to the throne, Maria Theresa, made a visit – and was then lost again in 1739. It would not be until the Peace of Sistova in 1791 that Orșova itself was conclusively acquired, while the island of New Orșova (known as Ada Kaleh to the Turks) remained in Ottoman hands.

The first trailblazer of future economic prosperity was the restless Count István Széchenyi, whose numerous transport development plans included making the Iron Gate navigable. In 1830, the count made a voyage through the gorge – to be repeated later another eight more times – and recorded his impressions in his diary: “The transparent clarity of the water and the silence of our journey were often undisturbed by anything, not even the quiet splashing of the oars; there were only the cries of the pilots urging their tugs and horses onwards. I was lost in gloomy thoughts about how far behind we have fallen. Would an English farmer or an American Yankee believe that the Hungarian peasant – the inhabitant of a land that declares itself happy and noble – is in such a mental and physical state that he voluntarily hauls a boat like a beast of burden, an occupation against which even the lowest slave would rebel?”

Plans for regulating the river were also supported by the government in Vienna; as a result, Széchenyi was appointed royal commissioner to oversee the regulation of the Iron Gate, and as a former soldier he could get on with the border guards. His diplomatic experience was also important as the borders of several states met in the region, and he had also acquired local knowledge of the area during his previous travels. Work began in 1833 under the direction of Pál Vásárhelyi as lead engineer, although Széchenyi participated throughout as a sort of “manager.” Although the idea of constructing a navigation channel was also raised, eliminating the rapids would have been enormously expensive given the technical abilities of the time, so only the most dangerous rocks were blasted, resulting in the river becoming navigable for 150 days a year.

Count István Széchenyi’s memorial plaque on the Széchenyi Road at the Iron Gate. The greatest achievement of Széchenyi's regulation effort was the building of the cliff road along the northern (left) bank of the Danube. This made it possible to haul shallow-draught barges through the gorge upstream, as it was impossible to navigate against the very strong current without towing. The photo clearly shows the herculean work involved in carving the road out of the rock. The memorial plaque was swallowed up by the Danube after the construction of the Iron Gate dam. For many decades afterward, an anchor scratched into the rock surface provided a rough approximation of where the Széchenyi plaque was located until a new sign was installed in 2018.

A road was also constructed along the left bank of the river to serve as a towpath in hauling shallow-draught barges across the rapids when sailing upstream against the fast current. Even if the barges were unable to navigate the river, goods could still be transported overland past the gorge. The work took place under trying conditions, as well evidenced by a letter addressed to Széchenyi from the three engineers on site in which they requested a salary increase: “Most of the autumn has been spent living in a hut stitched together with leaves, exposed to all the elements with no small decline in our health […] we are gambling with our most precious commodity – our lives – here at the rapids of the Iron Gate.”

Apart from the environmental and technical difficulties, establishing the diplomatic groundwork perhaps took up most of Széchenyi's energy. He had to overcome the resistance of the reluctant Ottoman Porte in addition to securing the support of the Serbian and Wallachian voivodes as well as reaching an agreement with the Tsarist government, which exercised a protectorate over the Romanian principalities at that time. The indefatigable count combined fine words with threats in securing the cooperation of all parties involved, thus ensuring completion of the road by 1837. In honor of both Széchenyi and this work, a memorial plaque was installed on the cliff alongside the road during the Dual Monarchy.

Emperor Trajan’s plaque at the Iron Gate, 1904. Near present-day Drobeta-Turnu Severin, at the eastern entrance to the gorge, the Emperor Trajan built the largest bridge in antiquity, the ruins of which exist to this day. The bridge assisted the Roman capture of the province of Dacia and ensured communications with it later on. The Romanians, who were committed to the theory of Daco-Roman continuity, held the emperor in high regard, for which he was also given a memorial plaque at the Iron Gate. This plaque would also have been swallowed up by the rising waters resulting from the dam, but they ensured that it was raised to a sufficient height at the same time the Iron Gate power station was being built.

The importance of this stretch of the frontier is clearly indicated by the fact that when the Prime Minister of Hungary, Bertalan Szemere, fled following defeat in the Hungarian War of Independence, in 1849, he buried the Holy Crown and crown jewels of Hungary here, at Orșova, near the Turkish border. Of course, the irreplaceable artifacts were eventually discovered by Emperor Franz Joseph’s agents following a tireless search. Later, a memorial chapel was built on the site where the crown was found.

The navigation channel for the Iron Gate gorge was completed at the end of the 19th century according to plans laid out by the Hungarian minister of trade and public works, Gábor Baross. The channel was formed by blasting on the southern (right) bank of the Danube and ensuring a consistent depth of 2 or 3 meters at average river height. Nevertheless, the current remained so strong that ships traveling upstream still had to be towed.

However, real economic prosperity came to the region only during the era of the Dual Monarchy. In 1878, the railway line between Temesvár (Timișoara) and Orsova was opened, allowing direct connection with both Budapest and Vienna. The same railway also had a beneficial impact on spa life at the Hercules Baths, whose railway station still bears the unmistakable style of the Monarchy and which stands out prominently from the dreary row of station buildings of the surrounding Romanian settlements. Recognizing the importance and the positive qualities of the area, the Danube Steamship Company (Donaudampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft) established a station in the bay formed by the Cerna River at Orsova. Later, a shipyard and free port were established in this easternmost border town on the Danube of the Kingdom of Hungary.

From the “Iron Minister” to the Emperor

However, navigation through the Iron Gate was still an unresolved problem for most of the year. In addition to the technical and financial difficulties, diplomatic complications also hindered implementation of the plan, as Romania on the north side of the gorge and both the Ottoman Empire and Serbia on the south obstructed the construction of the navigational channel. Moreover, the authorities lacked the necessary financial resources, on the one hand, while on the other, the amount of commercial traffic conducted on the Danube remained negligible. It was not until the Congress of Berlin in 1878 that the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was tasked with carrying out the regulatory work, although actual construction did not begin until 1890, largely due to the efforts of the well-known Hungarian transport minister of that time, Gábor Baross.

A choice had to be made whether to solve the navigability problem by means of dams and locks or by opening a channel. In the end, they decided on the latter, both for military reasons (as blowing up dams in case of war would make shipping impossible) and because they considered the latter option cheaper. The plans were developed by Ernő Wallandt, chief engineer of the Hungarian Ministry of Public Works and Transport, and a joint German-Hungarian venture – the Lower Danube-Iron Gate Regulation Company (Al-Dunai Vaskapuszabályozási Vállalat) – was established to carry out the work, using special drilling and chiseling vessels built in Scotland and Germany. The builder had to do an enormous amount of work, extracting 227,000 cubic meters of rock from the banks and 162,000 cubic meters from the riverbed. Baross, the “Iron Minister,” attended the first blasting but did not live to see the project’s completion.

Similar to today, practical considerations were overridden by higher interests, and the still unfinished canal was inaugurated during the Hungarian millennium celebrations in 1896 in the presence of Emperor Franz Joseph, who arrived for the event by train, along with the kings of Romania and Serbia. The fact that the steamer, named after the monarch present on board, sailing to the tune of the Emperor’s hymn “Gott erhalte (Franz den Kaiser),” or God Save Francis the Emperor, was decorated only with the Austrian dynastic black-and-gold flag instead of the Hungarian flag, caused great outrage in the Hungarian press at the time. It was a source of joy that Hungary was later able to collect fees from passing ships to cover the costs of the regulation.

Blasting and excavation work continued right up until 1899, as a result of which an 80-meter-long, 3-meter-deep navigation channel had been created on the Serbian side of the gorge, in the most dangerous section of the Iron Gate. The resulting channel allowed safe passage for steamships except during low water, extending the navigation season to 290 days. Nevertheless, it remained a problem that ships had to be towed upstream, even in the new channel, due to the very strong current. Memory of the regulatory work is still commemorated today by a huge carved stone tablet erected on the Romanian side under the Dual Monarchy and visible from afar. But plans did not stop there. In September 1918, the Hungarian minister of trade, József Szterényi, was already considering the construction of a major dam on the gorge, but nothing came of it due to the Austro-Hungarian defeat in World War I and the subsequent Treaty of Trianon.

Ada Kaleh (Turkish, “island fortress”) in 1949. Ada Kaleh existed as the last vestige of the Turkish world in the Iron Gate gorge since, following the Congress of Berlin, this small island was only under the nominal rule of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, with its day-to-day administration still conforming to the Turkish way of life. The island was the last peaceful territorial gain of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when the lord-lieutenant of Krassó-Szörény County, Zoltán Medve, brought it under direct Hungarian administration in 1913, shortly before the outbreak of World War I. This unique island, which captured the imagination of numerous travelers, was swallowed up by the rising waters of the Danube following the construction of the Iron Gate power station. Its buildings were moved to another Danube island, but its population did not accompany them; thus, the relocated buildings were left abandoned and have been reduced to ruins over the decades. The only reminder of the island today is an eponymously named viaduct on the Romanian side of the river.

The result of these developments was that the Iron Gate became a prosperous area by the beginning of the 20th century. A significant amount of goods traffic passed through Orsova, thanks to both rail transport on land and increased shipping due to improved navigability of the river. Moreover, as an important border town, it also generated significant customs revenues. The well-to-do, who came to the nearby Hercules Baths to cure themselves, if having ventured to the lower Danube, dutifully visited the picturesque gorge of the Iron Gate, the Holy Crown chapel, and even the island of Ada Kaleh. The latter was a particularly exotic sight at the time as it remained under Turkish rule as an enclave between Romania and Serbia on one side, which had gained independence in 1859 and 1867, respectively, and the Kingdom of Hungary.

The island used to have a predominantly military significance, with a modern fortress designed by Austrian military engineers. A Franciscan monastery was also established on the island in the 18th century. However, it was later reclaimed by the Ottomans, and thus uniquely in the world, a Turkish mosque operated within the walls of a baroque Christian monastery. It was not until the 20th century, however, that a minaret was built to accompany it, thanks to Sultan Abdulhamid, who paid special attention to the island. Ada Kaleh’s population of a few hundred people lived mainly from fruit and vegetable cultivation, while its unique situation as an enclave facilitated smuggling on the one hand and promoted tourism on the other, as more and more people wanted to visit the miniature Turkey that strangely remained on the border of Hungary and exuded an exotic atmosphere.

In 1878, a year of great uncertainty and upheaval in the Balkans, Austria-Hungary militarily occupied the island, but the civil administration remained in the hands of the Turks. It was not until 1913, that the lord-lieutenant of Krassó-Szörény County received instructions from the Hungarian prime minister to set sail from Orsova under war flags to occupy the island of Ada Kaleh and solemnly annex it to Hungary, thus achieving the last territorial gain of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy prior to World War I.

Destruction

The First World War and the subsequent peace brought an end to prosperity in the region in one fell swoop. Trade almost ceased as Austria-Hungary’s enormous internal market was divided into smaller nation-states that were hostile to each other and pursued protectionist policies. Naturally, the well-to-do public that visited the Hercules Baths also disappeared; the town, which exuded the atmosphere of the former monarchy from every brick, was never truly appealing to the Romanians. In the wake of the Second World War and the onset of socialism, development in the region was consciously neglected due to the proximity of a hostile Yugoslavia, a situation that changed only with Tito’s readmission to the socialist camp in 1956. Then, as a sign of Romanian-Yugoslav friendship, the two countries embarked upon a megalomaniacal joint venture – the construction of the Iron Gate hydroelectric power station – between 1964 and 1972.

The inland tug Sopron in the Iron Gate navigation channel, 1963. The navigation channel, like other gorge landmarks from the last century, was swallowed up by the Danube’s 30-meter-high water level following construction of the Iron Gate dam.

The destruction of villages initiated by Ceaușescu and the collapse of the church tower of Bözödújfalu (Bezidou Nou) into the reservoir that flooded the village are widely known in Hungary and are a sad reminder of this development. The construction of the giant hydroelectric power dam also resulted in a similar but much more brutal environmental transformation as the dam raised the Danube’s water level by 33 meters, thus irrevocably altering the nature of the landscape. However, the huge project did not end there; they also regulated the river’s outlet onto the Romanian plain (Câmpia Română), building the Iron Gate II hydroelectric power station some 80 kilometers downstream, which – as a lowland power plant – was completed at an even greater financial expense. The best-known part of the long winding valley of the Danube, with the roar of the Iron Gate, has completely disappeared; the previously spectacularly protruding cliffs have become small hills, and the entire winding river valley has been transformed into a large reservoir. Of course, the positive aspects include the large amounts of cheap electricity as well as safe navigation at all times of the year – but these were achieved at a terrible price.

The built-up environment suffered similar devastation. Perhaps the most visible victim of the continuous rise in water levels has been the island of Ada Kaleh. The island’s inhabitants were ordered to leave, most of whom left for Turkey, while others headed to Dobrudzha, along the Black Sea coast, which still retained a Turkish atmosphere. They tried to move some of the buildings to Simian Island near present-day Drobeta-Turnu Severin, but due to the lack of residents, conservation, and general attention, they have been completely abandoned and are now in a ruinous state. The mosque that arose out of the Franciscan monastery was not relocated, nor was the minaret, which – like the church tower in Bözödújfalu – remained a lasting reminder that the island of Ada Kaleh, which was likely the inspiration of Mór Jókai’s “No Man’s Island” (Senki szigete) in Az arany ember, had once existed here.

Babakay Rock at the entrance to the Iron Gate gorge, 1963. Located between present-day Golubac (Galambóc) and Coronini (Lászlóvára), at the western entrance to the Iron Gate, this rock once constituted a 15-20 meter high limestone spur rising out of the Danube. Only the tip of this spectacular rock formation now remains visible as a result of the Iron Gate dam. Its name means “old father” in Turkish.

Nothing reminds us of the former Turkish enclave today, other than the name of a viaduct that forms part of the river road running high above the former island on the Romanian side. The plaque on the right bank of the Danube commemorating the Emperor Trajan was raised higher so it is still clearly visible when sailing on the river today. The Széchenyi memorial plaque was not so fortunate as it was submerged (along with the Széchenyi road), and for a long time the only indication of its existence was an anchor carved into the rock above it. A few years ago, however, thanks to the efforts of the Hungarian Shipping Association, a worthy memorial plaque once again proclaims the tireless work of the “greatest Hungarian.”

Sailing through the Iron Gate today, one can still see breathtaking scenery, but the region’s former prosperity along with its historical monuments has disappeared. Despite this, the romance of the region lingers, and it remains an unmissable part of any trip to southern Transylvania or the southern Carpathians.

(translated by Andrea Thürmer and John Puckett)