Every year, on February 25, Hungarians commemorate the victims of the Communist dictatorship. On this day, in 1947, Soviet forces in Hungary seized Béla Kovács, member of parliament and general secretary of the rival Independent Smallholders’ Party, and deported him to the Gulag. This act was symbolic of the turning point which occurred in Hungarian history in the years 1947 and 1948, one which ushered in 40 years of Soviet-style communist dictatorship in the place of established European parliamentary democracy. Such violation of legal rights encapsulates the sacrifice and suffering of the victims of these forty years. In the shadow of this case stand all those martyrs of the revolution, the hundreds of thousands deported to Soviet camps, the hundreds executed on political grounds, the victims of show trials, the hundreds of thousands sentenced for political crimes, the 55,000 internees, the 20,000 deportees, the 80,000 B-listed as enemies of the communist regime, the half-million-strong army of peasants branded as “kulaks” and discriminated against by other oppressive means. And with them was a nation locked in falsehoods in the belief that they could lie their way to the truth. The legacy of the Rákosi and Kádár eras that oppressed people and nation alike still weighs heavily upon our necks. This date is symbolic of the forty years lost to an irrational and unviable economic and political system which consumed so much unnecessary energy that the writer Sándor Márai rightly described it as the cross between “a concentration camp and a madhouse.”

In the Hungarian parliamentary elections of November 4, 1945, the Independent Smallholders’ Party, which campaigned on freedom and parliamentarianism, won 57% of the vote. However, the Hungarian Communist Party also received nearly 17%, and with the backing of the occupying Soviet authorities and the Allied Control Commission, it set about its unstated goal of obtaining complete power. Until the fall of 1946, the contest remained positional in nature, with the Communists gaining decisive influence in the political police, the prosecutors’ offices, the courts, key economic positions (the Economic Council), public administration, trade unions, and the media (Hungarian telegraph, radio, and news agencies).

Mátyás Rákosi’s honeymoon with the Smallholders – the cooperation phase

“We went to Kaposvár for a front meeting. Since Somogy County was a stronghold of the Smallholders’ Party, the entire party leadership accompanied us on the train. We played 21 along the way and by the time we had reached Kaposvár the Communists had completely cleaned the Smallholders out. There was general consternation as Ferenc Nagy considered himself a good player and Béla Kovács especially so. We teased them that Communist superiority was evident in this area as well (Mátyás Rákosi, Visszaemlékezések).

The Independent Smallholders should have led the way in the struggle for democracy but due to the party’s misguided tactics – continuous concessions until sovereignty was restored – the initiative fell into the hands of the Communists. The party leadership lacked consensus on the right tactics to pursue. This “resulted” in the expulsion of Dezső Sulyok and twenty of his fellow deputies from the party in March 1946. Sulyok and his colleagues argued for more resolute enforcement of national determination and soon formed the Hungarian Freedom Party which waged a stirring battle in defence of democracy and freedom until July 1947.

The Independent Smallholders should have led the way in the struggle for democracy but due to the party’s misguided tactics – continuous concessions until sovereignty was restored – the initiative fell into the hands of the Communists. The party leadership lacked consensus on the right tactics to pursue. This “resulted” in the expulsion of Dezső Sulyok and twenty of his fellow deputies from the party in March 1946. Sulyok and his colleagues argued for more resolute enforcement of national determination and soon formed the Hungarian Freedom Party which waged a stirring battle in defence of democracy and freedom until July 1947.

The Freedom Party, with its astute leaders and courageous program – in which neutrality, a United States of Europe, and the primacy of Christian morality and social thought figured – eventually grew to rival the Smallholders’ Party. The immediate cause of the Smallholders’ breakup was the adoption of Act VII of 1946 which Sulyok and his colleagues rejected. Referring to the act as an “executioner’s law,” they viewed it as legislation that could lead to end of democracy in Hungary.

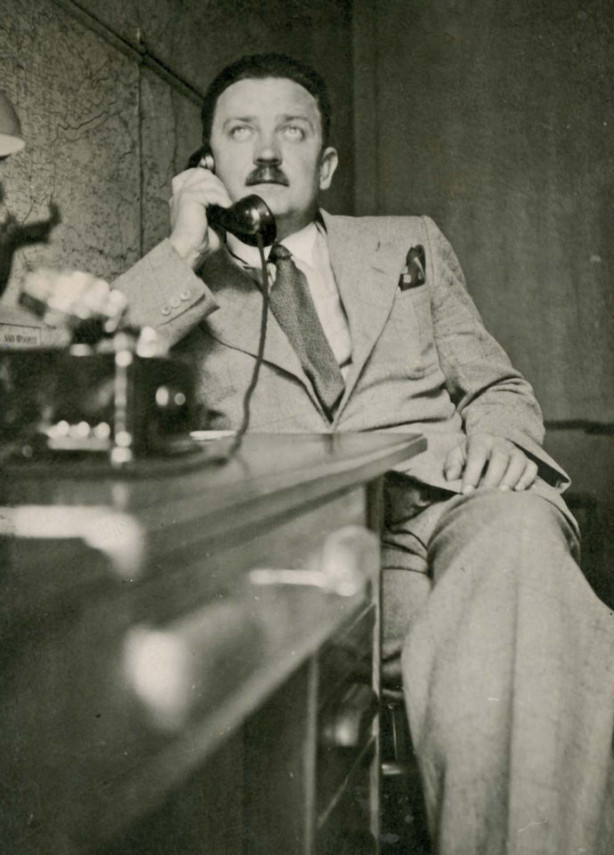

Béla Kovács (Patacs, April 20, 1908 – Pécs, June 21, 1959)

Béla Kovács was a smallholder peasant who joined the local and then national smallholder movement in the early 1930s. In 1939, he was appointed national deputy secretary general of the Hungarian Peasants’ Union and then secretary general in 1941. He became a member of parliament in the first postwar Hungarian parliament in 1944 and was then appointed in succession first as State Secretary for Internal Affairs of the Provisional National Government and then as Minister of Agriculture for a brief tenure lasting from November 1945 to February 1946. On August 20, 1945, Kovács was elected Secretary General of the Independent Smallholders’ Party and in March of the following year was appointed editor-in-chief of the party newspaper, Kis Újság. He was a close colleague of Ferenc Nagy, Hungary’s second postwar prime minister, and a supporter of sovereign smallholder policies against the Communist-led Left Bloc. Following his deportation from Hungary in 1947, he was held in prisons and camps in Soviet-occupied Austria, the Moscow region, and in Mordovia, near the Volga. He arrived home in 1955 on the last Soviet transport but remained imprisoned at the Jászberény prison until April 1956. When the revolution broke out in 1956, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Imre Nagy, included him in the government as Minister of Agriculture and then as Minister of State. On November 3, he was elected chairman of the Smallholders’ Party. After the defeat of the revolution, Kovács requested political asylum at the US embassy but was denied. The new communist leader, János Kádár, nominated him to the 1958 parliament for the purpose of compromising the smallholders’ movement and undermining Kovács’s own personal authority. Kovács did not have the strength to protest and died a few months later at the age of 51. He was rehabilitated by the Communist authorities in 1988.

Moreover, by autumn 1946, it had become obvious that there was little room for cooperation left between allies – the Cold War had begun. It was at this time that Mátyás Rákosi announced his intention to eliminate both the National Assembly and the Smallholders’ Party at a speech made to the Third Congress of the Hungarian Communist Party. The Communists called for early elections and a change in the composition of the ruling coalition. In short, they were aiming at obtaining sole power. The Smallholders’ Party was unfortunately unable to close ranks against the unfolding Communist coup and attacked the rival Freedom Party instead. Division and discord among the democratic forces eventually heralded their downfall. Perhaps the one that saw this most clearly was Béla Kovács, the General Secretary of the Smallholders’ Party. Autumn 1946 also saw the terms of the peace treaty ending Hungary’s participation in the Second World War. The treaty itself was signed in Paris on February 10, 1947 with Hungary’s sovereignty to be restored after September 15, 1947, following ratification and payment of reparations. According to Moscow’s plans, the “political turn” to Communist rule was to happen before then.

Mátyás Rákosi on Béla Kovács during the period of democratic suppression

“Despite growing internal dissatisfaction, however, the external edifice of the Smallholders’ Party remained without any major cracks […] A major change in this regard would occur with the arrest of Béla Kovács. Béla Kovács, the party’s general secretary and most influential leader, was then – alongside Zoltán Tildy and Ferenc Nagy – the most active representative of capitalism and the political right” (Visszaemlékezések).

This same period also saw the formation of fraternal societies which dreamed about the creation of a Hungarian democracy – without the Communists – following the restoration of sovereignty. One such fraternal society comprised the seven or eight people of Szent-Iványi Domokos’s circle of friends, which tried to organize itself in the footsteps of the former Hungarian Brotherhood (Magyar Testvéri Közösség). While the friends met, talked, and dreamed, the political police worked feverishly. They monitored (wiretapped) the leaders and headquarters of the Smallholders’ Party and put provocateurs to work. It turned out that this group of friends included Kálmán Saláta, Pál Jaczkó, László Gyulai, Tibor Hám, László Vatai, Sándor Kiss, János Horváth, and Vince Vörös – the latter a Smallholder representative. The main target was Saláta, who was accused of organizing the workers’ section of the Smallholders’ Party with the purpose of breaking the monopoly that the Marxist parties had over this segment of the population.

The battle was fought on many levels. The streets of Budapest were filled with large throngs who had been ordered out and provided with mass-produced signs proclaiming “Fascist conspiracy against the republic!” Defend the republic!” and “Out with the reaction from the coalition!” But the battle was also fought in the Ministry of Justice. While István Ott Ries, posing as a social democrat, served the will of the Communists, State Secretary Zoltán Pfeiffer did everything he could to ensure the primacy of the rule of law. Thanks to him (and the MP Dezső Futó) many foul deeds were exposed such as the Communist-led mass murders in the Győmrő area in the spring of 1945 and the illegal activities of the Communist police. As long as Pfeiffer remained in the justice ministry, show trials were rarely held in Hungarian courts.

The trial of Father Szaléz Kiss, which resulted in a death sentence, was eventually heard by a Soviet military court. The trial was significant since according to the formulation it was supposed to incriminate Béla Kovács and even Cardinal József Mindszenty through the aegis of Kiss’s organization. Thus, this trial already contained essential elements of the two most influential Hungarian show trials of 1947 and 1949. However, “a mistake entered into their calculations” as the father proved unwilling to cooperate and was likely beaten to death instead.

By December 1946, the pressure on the Smallholders had become so great that Pfeiffer was forced to resign from the Ministry of Justice on December 18. The Communist press referred to him as the “chief fascist charlatan” and the Smallholders’ leadership yielded again. A few days later, the State Protection Department (ÁVO) issued a communiqué regarding a “conspiracy against the republic.” However, extraordinary events had taken place beforehand, including the arrest of parliamentary (Smallholder) representatives despite their immunity. The arrests were used to manufacture “evidence” obtained without exception through forced confessions extracted in the interrogation chambers.

József Mindszenty regarding the events of November 4, 1956:

“Suddenly someone called out: ‘There may be an air raid; get to the shelter!’ Down there I met Béla Kovács, the former Secretary General of the Smallholders’ Party and now an acting minister, who had returned after seven years of Siberian captivity and illness. He was accompanied by four or five leading politicians and we got to talking. As a politician, I regarded Kovács as a man of upstanding character, honest and prepared to make sacrifices. When I looked for him at the embassy the next day I learned he had been denied amnesty and had gone home ill to his native village in Baranya… I felt very sorry for him and wondered what would become of him” (Emlékirataim).

In a corner room at Andrássy út [avenue] 60, Gábor Péter, the head of the State Protection Department, was already outlining the scenario of a great conspiracy, which would help disrupt the Independent Smallholders’ Party and eliminate its popular leaders – Béla Kovács, Ferenc Nagy, and Béla Varga. The first target was the “evil genie” Béla Kovács who made repeated declarations that the Smallholders were not prepared to make any further concessions. Most of all, he was opposed to the holding of early elections. The ÁVO used every means available – both physical and mental torture – and soon the confessions were drawn up, according to which Béla Kovács had given orders for an “armed espionage organization.”

The Smallholders backed down once again and expelled their arrested representatives. At the same time, however, the National Assembly refused to rescind Béla Kovács’s immunity. This was the moment when the National Assembly, which embodied the will of the people, confronted the occupiers and their lackeys – the Communists. It was a tense situation. Would the parliament, relying on the popular vote, emerge victorious, or was there a greater force? Would parliament’s decision be overridden by an external power and its aggressive servants?

This was when the democratic forces needed to demonstrate firmness and unity. Instead, frightened and resigned to his situation, Béla Kovács left Budapest for his native village. But even this failed to satisfy Rákosi and his people who proceeded to round up almost 260 people. Justification for the arrests was based on the “executioners’ law.” Ference Nagy, however, sought a “compromise” even now. He agreed with Rákosi and Árpád Szakasits, the Deputy Prime Minister, that Béla Kovács would report to the State Protection Department at Andrássy út 60 and submit to questioning – but he was not to be arrested. However, this was just as illegal as the earlier arrest of the Smallholders’ representatives. As Dezső Sulyok noted in a speech to parliament: “A state that does not honor its own laws and is divided against itself will not last. We cannot ignore the law, no matter how great the danger.” Rákosi, Szakasits and Nagy were indignant. “Fascist” – hissed someone from the Communist ranks.

Zoltán Pfeiffer on Andrássy út 60

“‘I made it clear [to Gábor Péter and László Rajk, Minister of the Interior] that I would not be party to the conflict. I would open every door until I found Kovács, and it didn’t matter if they arrested me. I still don’t know today,’ he wrote in 1972, ‘why they were so afraid of a scandal, but Rajk phoned the chief of police to bring him to me at once. A few minutes later, Béla Kovács was there with me. I barely recognized him. His manly figure had shrunken and terror was written on his friendly face. ‘I won’t survive this,’ he said with a groan” (Wisconsini Magyarság).

The Béla Kovács case had acquired symbolic importance – would parliament be able to overcome the brutal calculations of the (ruling) party? The chief editor of the Communist daily Szabad Nép, József Révai, did not mince words: “All signs point to the fact that no matter how much certain [Smallholder] leaders seem to be relaxing their position and no matter how much fracturing there is, this company will only break up if we strike a blow and start cleaning house."

More crowds were ordered onto the streets while Béla Kovács was summoned back to Budapest. Ferenc Nagy and Béla Varga informed him about the “agreement,” according to which he had to go to Andrássy út 60. Béla Kovács knew what awaited him at the former Arrow Cross headquarters: torture, physical torment, and mental terror. But they presented him with the ready-made “facts,” especially that he had allegedly already signed the agreement. He would have preferred to address parliament in order to explain himself, but the Smallholder leadership – including President Zoltán Tildy – persuaded the former Secretary General to comply with the Communists’ demands. This happened on February 25, 1947.

More crowds were ordered onto the streets while Béla Kovács was summoned back to Budapest. Ferenc Nagy and Béla Varga informed him about the “agreement,” according to which he had to go to Andrássy út 60. Béla Kovács knew what awaited him at the former Arrow Cross headquarters: torture, physical torment, and mental terror. But they presented him with the ready-made “facts,” especially that he had allegedly already signed the agreement. He would have preferred to address parliament in order to explain himself, but the Smallholder leadership – including President Zoltán Tildy – persuaded the former Secretary General to comply with the Communists’ demands. This happened on February 25, 1947.

Gábor Péter and police investigator István Tímár’s henchmen immediately began working on the Smallholder representative. Insults ranging from “stinking peasant” to “rotten fascist conspirator” were heaped upon him. His browbeaten friends accused him of being a “conspirator,” a spy, and so on. Abused and overwhelmed, Kovács was on the point of collapse. It was then that Zoltán Pfeiffer appeared at the infamous ÁVO headquarters – as a lawyer – and demanded to be taken to Béla Kovács. The flustered security officials let Pfeiffer in; he was, after all, a member of the political committee of the largest government party, a former state secretary of justice, and a well-known member of the anti-fascist resistance. Kovács was already on his last legs by then, his face frozen in terror.

Pfeiffer had made a bold decision and what was more surprising, Gábor Péter (on orders from Rajk and even more so from Svirodov, the deputy chairman of the Allied Control Commission) let them out of the building. They thought they had managed to escape. They went to Ferenc Nagy and insisted that Kovács still address parliament. Then they went to Kovács’s apartment on Váci utca, in the city center. Around eight o'clock in the evening, Soviet soldiers appeared in front of the house. They rang Béla Kovács’s doorbell and told him to come with them. What could he do? – He left. Allegedly all he could say was “Feri.”

And so, Béla Kovács was taken away, in violation of his immunity. This seemed easier than having to haul the popular Smallholder leader before a Hungarian court. It became obvious that the will of the Hungarian people, the legal system, parliament, the Prime Minister (Feri), the President of the Republic, and others were powerless to do anything about it. A diplomatic note was issued in the West but this already amounted to indifference. Fear spread throughout the country, although there was still room for resistance. Béla Kovács would join the ranks of hundreds of thousands of Hungarians and millions of Europeans who were taken away by the Soviets. He was sent to the Gulag, without a proper trial or court sentence. It was not until 1955 that he was allowed to return home and was finally released only at the beginning of 1956.

At the February 26, 1947 session of the National Assembly, the Speaker of the Assembly, Béla Varga, made a brief announcement: “Honorable National Assembly! I bring to the National Assembly’s attention what is now common knowledge that Member of the National Assembly Béla Kovács was taken into custody by the Soviet military authorities on the 25th of this month. I have communicated this fact to the government.” The National Assembly acknowledged the announcement without a word. It was exactly one day earlier, two years previous, on February 27, 1945, that the Speaker of the National Assembly had informed the house of the execution of the MP Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky in Sopron. The fate of these two Smallholder leaders constitutes a symbolic weight on our history of the 20th century.

Mátyás Rákosi put it this way: “The reaction immediately tucked in its tail… I soon saw for myself that the Soviet comrades were right when they took matters into their own hands” (Visszaemlékezések).

The rest of the story followed the Communist script. Soon, “incriminating statements” were being made against Prime Minister Ference Nagy and he too became an “anti-republican conspirator.” He was overthrown in a coup on May 31, 1947. Béla Varga emigrated, as did Dezső Sulyok. The Freedom Party boycotted the early elections called for August 31. Zoltán Pfeiffer, meanwhile, formed the Hungarian Independence Party and threw himself into the election campaign. The electoral laws for the August 31, 1947 elections were altered, however.

Prior to the election, some 600,000 people – all of them of a Christian, nationalist, or possibly social democratic persuasion – were excluded or “left off” the voting lists. On the election day itself, Communist activists (some 12,000 people) traveled around the country casting 208,000 false votes by means of the infamous “blue ballots” – forged registration slips allowing for absentee voting in other districts. The results, however, still failed to meet Communist expectations. The democratic parties received 54,5 % of the votes. Rákosi did not hesitate. He labeled the Independence Party “fascist” and annulled its 670,000 votes and 49 mandates. Thus, the Hungarian left gained an absolute majority in parliament, and parliamentarism came to an end.

Thus, the Yalta dilemma, and Hungary’s ambiguous status, was resolved. The “year of change” followed and Hungary went down the road of proletarian dictatorship.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)