The second Soviet military intervention in Hungary began on Sunday, November 4, 1956, at dawn, within the framework of Operation Whirlwind. The armed resistance of the freedom fighters managed to hold out for nearly a week against overwhelming odds. However, the Soviet military victory was far from being a political victory for the new regime. Rear-guard action continued against the Soviet troops and what was considered an illegitimate government. Armed resistance shifted to mass, open political opposition. The national committees and workers’ councils, which continued to function despite the Soviet occupation, became the main arenas for this resistance. Their substantial mass support and nationwide mobilizing power demonstrated that the revolution still had reserves and threatened Kádár’s unstable puppet government with the specter of dual power due to its rejection by society.

The onset of reprisals

On November 4, 1956, Hungarian Communist leader János Kádár promised to end the internecine fighting that had broken out in October, restore order, and bring internal peace. Although he publicly declared “life without fear” as late as November 26, in order to crush social resistance and consolidate his power, the old-new party leadership, under significant pressure from the Communist parties of the neighboring Soviet countries, ultimately resorted to violence. By November 16, at a meeting of the Provisional Executive Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP), Kádár (following a discussion with the Chinese ambassador) was already advocating for a dictatorship. He explained that the Chinese people referred to their own system as a people’s democratic dictatorship, “which embodies the essence of our own system: democracy for the people and dictatorship against the counter-revolution. [...] In the current situation, the focus must be on dictatorship,” he added.

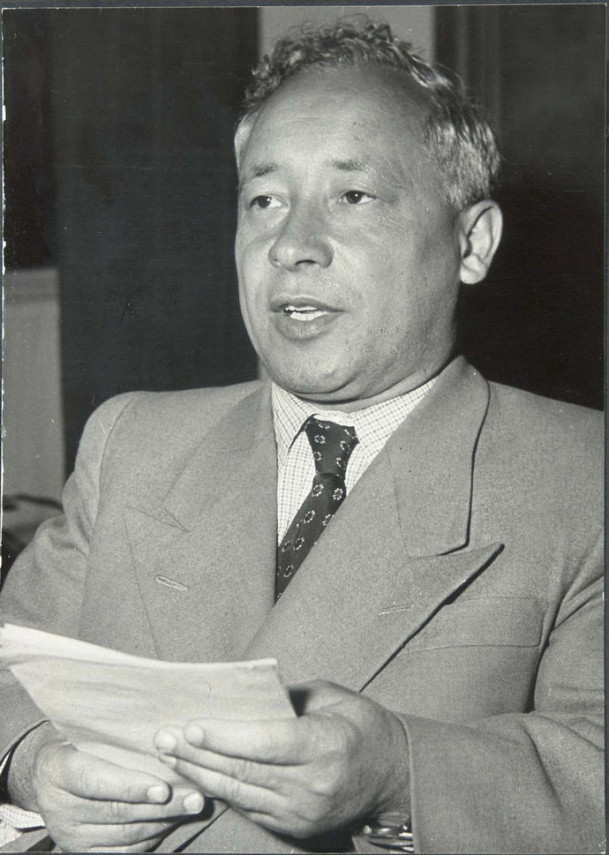

Chairman of the Military Council of the Ministry of Defense

in November 1956,

organizer of the military police forces.

However, without armed forces of its own, the government could not take decisive action against the population who was protesting the Soviet occupation and the restoration of the communist regime. In the initial period, the disintegration of the Hungarian state and internal structures meant that Kádár had virtually no organized base of his own. Kádár could only maintain order with Soviet assistance, with his actions being directly controlled by high-ranking Soviet officials from behind the scenes. This situation began to change in mid-November.

On November 22, three high-ranking Soviet party officials ‒ Aristov, Malenkov, and Suslov ‒ were dispatched to Budapest. They reported to Moscow that “in order to identify and eliminate the illegal centers of rebellion, our state security agents, in collaboration with the Hungarian police, will continue to detain and arrest the most active participants of the armed uprising. A total of 1,437 arrests and 5,820 detentions have been made [...].” The same report also mentioned that Ferenc Münnich, Deputy Prime Minister, was receiving assistance in reorganizing the political police from a State Security group led by I. Serov, the powerful KGB chief, who had been in Hungary since October.

Crushing the revolutionary resistance

The Kádár government’s most pressing priority was to create an effective and unconditionally loyal armed force to consolidate its power and to begin reprisals. While the reorganization of internal state defense began in secret immediately after November 4, 1956, with strong Soviet support, the ÁVH (State Protection Authority) was so deeply despised by society that the new leadership could not openly pursue its reorganization. As a result, the Party’s own paramilitary forces, commonly known as the “padded jackets,” were formed. These forces, composed of former party functionaries, reserve officers, military personnel, and, to a lesser extent, police officers, were prepared to begin the violent suppression of social resistance in early December, with the assistance of the Soviet military. By that time, the combined strength of the “padded jackets” in Budapest and the countryside had increased to about 10,000.

The ideological basis for the politics of violence was laid out in a resolution by the Provisional Central Committee of the MSZMP in early December after being in session for several days. After conducting an internal assessment of the October-November events, the committee unanimously classified the revolution as a counter-revolution and considered armed combat justified to fight the “counter-revolutionary” threat. While the Party publicly distanced itself from the methods of the Rákosi era, in practice, it was returning to its dictatorial methods. Though Kádár had considered integrating some of the revolutionary forces until early December, he decided to use brutal force in response to social resistance instead. The Party leadership resolved that the MSZMP should impose order by use of arms.

In the months following November 4, extrajudicial reprisals were typically linked to the operation of the armed forces. The actions of the “padded jackets” led to indiscriminate brutality, involving the abuse, torture, and sometimes even murder of scores of civilians. As Ferenc Münnich’s military deputy, Gyula Uszta, who also supervised the military police forces, remarked at a Military Council meeting on December 4, 1956: “They [the revolutionaries] must be quickly and ruthlessly eliminated.” The Military Council received political orders to take armed action. In December, several mass shootings occurred, targeting unarmed demonstrators and the general population, first in Budapest, at the Western (Nyugati) Railway Station, then in Salgótarján, Miskolc, Eger, and several small towns in the countryside, and finally, on January 11, 1957, against the workers of Csepel.

the staunchest representative of the politics of reprisals,

is famously quoted as saying,

“Starting today, we shoot!”

Research by Frigyes Kahler and Sándor M. Kiss highlights that the second wave of the December-January crackdowns was explicitly aimed at crushing resistance, instilling fear, and breaking social solidarity. The political intention behind the mass shootings was most starkly captured in the infamous statement of György Marosán, the Minister of State, during his meeting with the Nógrád workers’ delegation: “Starting today, we no longer negotiate; starting today, we shoot.” According to investigations, the shooting in Salgótarján that day resulted in 50 to 130 deaths. According to medical reports, most of the victims shot in the back while trying to escape

A day after the Salgótarján massacre, on December 9, 1956, two National Guard leaders from the steelworks, Rudolf Hadady and Lajos Hargitay, were tortured and killed, their bodies dumped into the Ipoly River. The next day, the Kádár government shifted the blame for the massacres onto the workers’ councils, outlawing them and launching a wave of mass arrests targeting workers’ leaders and those involved in the resistance after December 4. Then, on December 11, martial law was declared, marking the beginning of an intensified crackdown and a new phase of reprisals.

The institutional framework of the reprisals

At the end of 1956 and in the early months of 1957, a strategy for reprisals was devised, and the institutions responsible for carrying them out were established. Among the institutions operating within a legal framework, it was mainly the personnel of the police forces, prosecutor’s offices, and judiciary who had to be prepared for their “tasks.” To ensure that the machinery of reprisals functioned smoothly, a “purge” was conducted within all three organizations to remove any police officers, prosecutors, or judges who sympathized with the revolution.

In November and December of 1956, the responsibilities of the ÁVO-ÁVH were transferred to the departments and divisions overseeing political investigations. Although reactivating the former state security officers posed a considerable challenge for the Kádár government, it became clear that, lacking genuine mass support, Kádár could only rely on the state security apparatus to uphold the communist regime. Researchers Attila Szakolczai and Magdolna Baráth suggest that while the ÁVH was not formally reorganized, its personnel and functions were essentially incorporated into the political investigation department of the police as its successor. Members of the former ÁVH apparatus were transferred en masse to the “newly” created investigation departments. By January 1957, some 5,000 state security officers had been screened, with only 15 failing to pass. However, the purpose of the screening was not to evaluate the former personnel but rather to legitimize the state security apparatus. Colonel László Mátyás, head of the Political Investigation Department, offered a candid assessment of the lawfulness of their actions at a meeting of the National Police Headquarters in late December: “It is true that we did not use legal means to crush the counter-revolution [...] When there are extraordinary circumstances, extraordinary measures have to be taken [...] If I must defend proletarian power and can only do so by confronting the counter-revolution with illegal means, then this cannot be condemned.”

Legal justification for reprisals

For the authorities to carry out reprisals effectively, criminal procedure had to be reformed. To maintain the appearance of lawfulness, the Kádár government issued decrees aimed at eliminating “counter-revolutionary elements.” Extensive research from Frigyes Kahler and Tibor Zinner into legal history reveals that establishing the institutional framework for reprisals involved four key components: the introduction of summary punishment, accelerated trials, the creation of the Supreme Court’s Council of People’s Tribunals, and the establishment of people’s tribunals throughout the country.

November 4,1956 as deputy prime minister of the Hungarian

Revolutionary Workers’ and

Peasants’ Government under János Kádár,

in addition to holding the post of Minister of the

Armed Forces and Public Security.

The main legal form of reprisals during the period was the martial trial. The draft law on summary executions (martial law), prepared by Sándor Feri, then a Supreme Court judge, was promulgated on December 11, 1956. The purpose of the summary (military) courts was the quick restoration of social order. This was reflected in a decree that provided for summary punishment in cases of intentional manslaughter, arson, looting, damage to public utilities, and the unauthorized possession of firearms and explosives. Moreover, crimes that fell under the rubric of vandalism of public enterprises included strikes, work slowdowns, and faulty production, or the incitement thereof. With the introduction of martial law, the authorities aimed not only to punish and instill fear in those directly involved in the Revolution but also to intimidate society as a whole. Only about half of those convicted were tried on the grounds of their participation in the Revolution. The first death sentence under these decrees was passed and carried out on December 15, 1956: József Soltész was shot at the Miskolc infantry firing range for hiding weapons. Over the year that the summary courts operated, 513 individuals were tried; 70 were sentenced to death, 72.6% received sentences of 10 to 15 years in prison, and 9.6% were sentenced to 5 to 10 years in prison.

However, martial law was not enough to satisfy those in power who sought to intensify the reprisals. As a result, they established legal conditions for accelerated procedures, which followed similar criteria but involved the judiciary in civil cases. Tibor Zinner’s research highlights that it was during this period that members of the judiciary who refused to participate in the reprisals resigned. The legislation, prepared by József Domokos, Ferenc Münnich, György Marosán, and Ferenc Nezvál, also allowed prosecutors to bring the accused to trial without an indictment if they were caught in the act or if the evidence was immediately available to the court. A decision by the Presidium of the Supreme Court clarified that the accelerated procedure applied to all other criminal offenses of the accused, even if those offenses were not part of the accelerated procedure.

By April-May 1957, following János Kádár’s negotiations in Moscow in March, the legal framework and organizational structure for the planned and mass punishment of the participants of the Revolution was ready. The Supreme Court’s Council of People’s Tribunals was established by decree 1957:34, followed by five more people’s tribunals during the summer. By establishing political courts that operated on a regional basis, a legal institution was created that proved capable of handling the mass trials of retaliatory political cases. Kádár first articulated his views on establishing a tribunal for the most severe political crimes during a meeting of the Provisional Executive Committee of the MSZMP on April 5, 1957. He stated: “Horthyist military officers, gendarmes, and others have become active in the country and seized power. A people’s tribunal should be set up, and wherever we find Horthy sympathizers who have committed heinous acts, they should be tried in procession, sentenced to death, and executed. If this does not happen, the people will never live in peace here. These verdicts should not be published in the newspapers.”

The decree on the people’s tribunals disadvantaged the defendants in several ways. Notably, it disregarded the principle of “reformatio in peius” (“change for the worse”), allowing death sentences to be imposed even on appeals seeking only mitigation. Additionally, the Council of People’s Tribunals had the authority to review legally binding cases, effectively enabling it to reopen any case that did not align with the political leadership’s desires. The most brutal aspect of the decree, however, was that it permitted the death penalty to be imposed on juveniles under 16 at the time of the offense. Tibor Vágó’s council took advantage of this provision in the case of Péter Mansfeld.

Thus, Kádár’s apparatus was equipped with a “court” that outwardly resembled a council of judges while enabling unlimited reprisals. It was ideally suited to enforcing the will of the political leadership. Furthermore, the political leadership directly intervened in the decisions of the Council of People’s Tribunals. The decree remained in effect until April 16, 1961.

Social class as a distinguishing factor

The sentences were not solely based on the offense committed. As outlined in the December party resolution, it was also essential to demonstrate that the leaders of the “counter-revolution” were class enemies. Enforcing the class aspect was a key element in the administration of retributive justice, but the courts failed to do so ‒ despite attempts to manipulate statistics. A November 1958 report revealed that nearly 26.5% of those executed or imprisoned were workers, and 31% were peasants. Only 6.6% were classified as “class enemies.” More than 90% of those arrested were from the social groups the regime considered its support base, including workers, peasants, lower-middle-class individuals, intellectuals, and employees who were not labeled as class enemies. As a result, pejorative terms such as “vagabond,” “hooligan,” and “prostitute” were used to describe the victims of the reprisals.

Party control of reprisals

The reprisals following the suppression of the 1956 Revolution and Freedom Fight were driven by the decisions of the highest political leaders and aligned with the internal logic of the party-state dictatorship. The Party leadership tightly controlled the political direction and focus of these reprisals, setting clear objectives and overseeing their execution. The Political Committee’s resolution “On Certain Aspects of the Fight Against Internal Reaction,” issued on July 2, 1957, laid the practical groundwork for the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the judicial practices that followed. The highest political leaders called for “strict and unified” action, emphasizing that “both the indictment and the verdict must reflect the oppressive functions of the proletarian dictatorship.” The Party resolution further instructed the prosecutor’s office and the Ministry of Justice to ensure that “the guilty counter-revolutionaries receive the punishment they deserve.”

Following the established guidelines, the first summary of the reprisals and their “results” was presented on December 10, 1957. A proposal by Béla Biszku, Minister of the Interior, Ferenc Nezvál, Minister of Justice, and Dr. Géza Szénási, Prosecutor General, to the Political Committee of the MSZMP on “Certain Issues of our Penal Policy,” along with the minutes of the subsequent debate, became some of the most frequently cited documents. These documents highlight that the comrades openly demanded harsher sentences from the courts. Béla Biszku, the Minister of the Interior, is often quoted as having lamented that there were “many light sentences and relatively few cases of physical annihilation” in the prosecution of revolutionary conspirators. During the same meeting, Kádár noted that they needed to address penal policy because “we have not been able to achieve the major physical annihilation of the main leaders of the counter-revolution.” By October 1957, 110 of the 180 individuals sentenced to death for their involvement in 1956 had already been executed.

The party headquarters held regular consultations with the heads of the Interior Ministry and the judiciary. In 1957, a secret yet powerful body called the Coordination Committee was established. It consisted of the Secretary of the MSZMP Central Committee responsible for Administrative Affairs, the Head of the Public Management and Administrative Department (KAO), the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Justice, the Prosecutor General, and the President of the Supreme Court. The committee was tasked with coordinating between the party leadership, the Ministry of the Interior, and the Ministry of Justice to ensure that the direct influence of the political leadership was maintained.

However, the restored Communist power never tried to conceal its denial of judicial independence.. As Lajos Borbély, who personally sentenced 62 people to death, emphasized at a meeting of the joint party organization of the Supreme Court and the Prosecutor General’s Office: “True judicial independence means that judges can, under no circumstances, be influenced in a way that goes against the interests of the working class and that they must always serve proletarian power.” Dr. József Domokos, President of the Supreme Court, in his speech on March 28, 1957, demanded nothing less than the following: “Let us learn a little class struggle from fascist judiciary [...] we are the judges of the Hungarian People’s Republic, the judges of the proletarian dictatorship, whose duty it is to reinforce the proletarian state and mercilessly destroy all its enemies who threaten the proletarian revolution.”

Target groups

The first phase of prolonged mass reprisals is regarded as a period of unrestrained retaliation. At that time, the reprisals did not have any clearly defined target groups, and the Kádár regime lashed out against the whole of Hungarian society without discrimination. In the second and longer main phase of the reprisals, however, the party had already identified the groups and activities it wanted to sanction most severely. The Party Resolution of early December 1956 also pointed out the main lines of the struggle for so-called consolidation – and retaliation. According to the resolution, there were four primary reasons for the 1956 outbreak of the “counter-revolution.” The first of these was the doctrinaire policy of Rákosi; the second, the revisionist activities of the Imre Nagy group; the third, the internal counter-revolutionary forces; and the fourth, the external counter-revolutionary forces. The first of the famous “four causes” did not have any penal consequences. The Rákosi group was not held legally responsible, presumably upon Moscow’s instructions. However, points 2 to 4 appeared within the rubric of criminal law.

The verdicts of the trials following the Revolution and Freedom Fight point in at least three directions. First, the so-called revisionist communists, who rebelled against the dictatorship and called for reform, were suppressed. Among the victims were Prime Minister Imre Nagy and his associates, who ‒ from the perspective of Kádár and his comrades ‒ had opened the door to the “fascist counter-revolution” and, whether knowingly or unknowingly, became traitors and supporters of the revolution. This group also included the legendary revolutionary István Angyal, who had a dispute with Imre Nagy. These trials revealed that Soviet-style communism would not tolerate reforms unless they originated from within the system.

Another group of trials targeted the armed freedom fighters. Their resistance was met with punishment by the authorities, and the majority of the death sentences imposed and carried out were directed at them. Among those executed was the legendary leader of the Széna Square rebels, Uncle Szabó, as well as János Bárány, who led the insurgents on Tompa Street, László Iván Kovács of the Corvin Lane rebels, László Nickelsburg of the Baross Square group, and Miklós Gyöngyösi, sentenced to death in the Ilona Tóth trial.

Another distinct and significant group of trials targeted the leaders of the national councils and revolutionary committees. During the Revolution and the Freedom Fight, a typical social revolution occurred, especially in the countryside. The Soviet-type council system was dismantled one by one, without violence. Within days, new municipal bodies based on genuine self-government ‒ the National Committees ‒ were established even in the remotest villages. These committees soon elected their own dedicated and respected leaders, such as Dr. Árpád Brusznyai, a teacher in Veszprém; Gábor Földes, a film director; Attila Szigethy, a politician; Árpád Tihanyi, a teacher in Győr; Lajos Gulyás, a minister of the Reformed Church in Mosonmagyaróvár; Márton Rajki, a lawyer; Pál Kósa, a carpenter in Újpest; Károly D. Szabó, a tram conductor in Ócsa; József Kováts, a medical student in Szeged; Károly Szente Sr., a carriage driver in Csepel; and Dr. Zoltán Szobonya, a lawyer in Jánoshalma. Although their political convictions and their social backgrounds varied considerably, they had one thing in common: their active opposition to Soviet-style socialism. The reprisal trials and death sentences that were imposed on almost every local community as a tool of terror were aimed at dismantling the social network of trust and solidarity that threatened the hegemony of the re-established dictatorship.

The end of the reprisals

Ferenc Nezvál, Minister of Justice (1957-1966),

a key figure in the reprisals of the Kádár regime

Most of the trials for participation in the 1956 revolution took place between 1957 and 1959. The last execution connected to the Kádár reprisals was carried out on August 26, 1961. On that day, the Baross Square rebels István Hámori, Lajos Kovács, and László Nickelsburg, convicted in the trial of Benjámin Hercegh and others, were handed over to the executioners. Benjamin Hercegh was released from prison in April 1975 after serving exactly fifteen years. However, the other two persons sentenced to life imprisonment in the trial did not live to see their release: Péter Antal died in prison in April 1974, and József Mocsári passed away in August 1970.

As the Hercegh trial demonstrates, the 1963 amnesty, hailed by Kádár’s propaganda as the end of the reprisals, did not provide reprieve for many prisoners, as they did not receive full pardons. Although 3,480 individuals were released under the 1963:4 decree, the convicted barricade fighters of the revolution remained imprisoned. The decree excluded repeat offenders and rebels who had been declared public criminals by the authorities, mostly those armed fighters who had fought under oath and killed Soviet soldiers during the Freedom Fight.

As a result, even after 1963, many 1956 revolutionaries remained in prison. Astonishingly, reprisals continued well beyond that period. In 1966, a decade after the Revolution’s outbreak, some individuals were still being imprisoned for their involvement in 1956, as demonstrated by the case of István Papp, who was sentenced to ten years in prison.

(translated by Márta Pellérdi)