In May 1921, some three years after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, members of the Viennese Society for Private Musical Performances [Verein für Musikalische Privataufführungen] organized a special concert featuring the waltzes of Johann Strauss the Younger arranged for a chamber ensemble. The society was founded by Arnold Schönberg, and its membership consisted largely of his students and acquaintances, including the composers Alban Berg and Anton Webern, who also prepared and performed the transcriptions.

The evening’s program also included a performance of the “Treasure Waltz” [Schatz-Walzer] from Strauss’s operetta The Gypsy Baron [Der Zigeunerbaron (1885)], as transcribed by Webern. It is both surprising and amusing to see the names of leading local avant-garde composers listed on a concert program featuring the works of one of the most popular nineteenth-century operetta composers. It was indeed a rather special concert – although the Society had been established in 1918 for the private promotion of contemporary music, the idea for the Strauss evening was actually born of necessity. Amid the financial difficulties in the years following World War I, it may have seemed desirable to undertake the performance of works that could contribute to replenishing the Society’s coffers.

Eight years later, on November 4, 1929, Ernő Dohnányi, the director and conductor of the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra, played his own transcription of The Gypsy Baron’s “Treasure Waltz” at a piano recital held at the Pesti Vigadó, which also featured compositions by Brahms, Beethoven, and Mozart. Reporting on the concert, the respected critic of the Pesti Napló newspaper, Aladár Tóth, observed that “Dohnányi plays with youthfulness… By interpreting [the music] in different ways, Johann Strauss remains eternally young.” But why would Tóth have seen the music of Strauss’s operetta as something eternally young in 1929? And how did Vienna’s leading avant-garde composers come up with the idea of performing The Gypsy Baron’s “Treasure Waltz” and similar dance music at their concerts?

The two transcriptions mentioned above provide repeated confirmation that operetta was indeed a common and everyday experience for those living in the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Monarchy at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The premiere of Strauss the Younger’s The Gypsy Baron took place on October 24, 1885, at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien. The libretto, written by the Austrian-Hungarian librettist Ignaz Schnitzer, is based on the Hungarian author Mór Jókai’s eponymous short story, although the name of the male protagonist was changed from Jónás Botsinkay to Sándor Barinkay (Szaffi, the gypsy girl, retained her name).

Austrian historian Móritz Csáky, who has studied the relationship between the ideology of operetta and Viennese modernity, made note of the fact that Strauss’s work “takes place in the Banat of Temes in southeastern Hungary, [thus] referencing the multinational component prevailing in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Many representatives of the educated Austrian bourgeoisie knew – either from their school studies or from personal and family ties to the Banat – that Temes County was the best example of many nationalities and diverse cultures living side by side. The diverse ethnic composition of this small Hungarian subregion, where Hungarians, Serbs, Romanians, Bulgarians, Germans (Swabians), Jews, and Gypsies (Roma) coexisted, could be viewed as an ethnic and cultural microcosm of the Kingdom of Hungary and the entire monarchy itself – a monarchy that saw an increase in internal conflicts in the nineteenth century, with many attributing the cause of these conflicts to ethnic issues.”

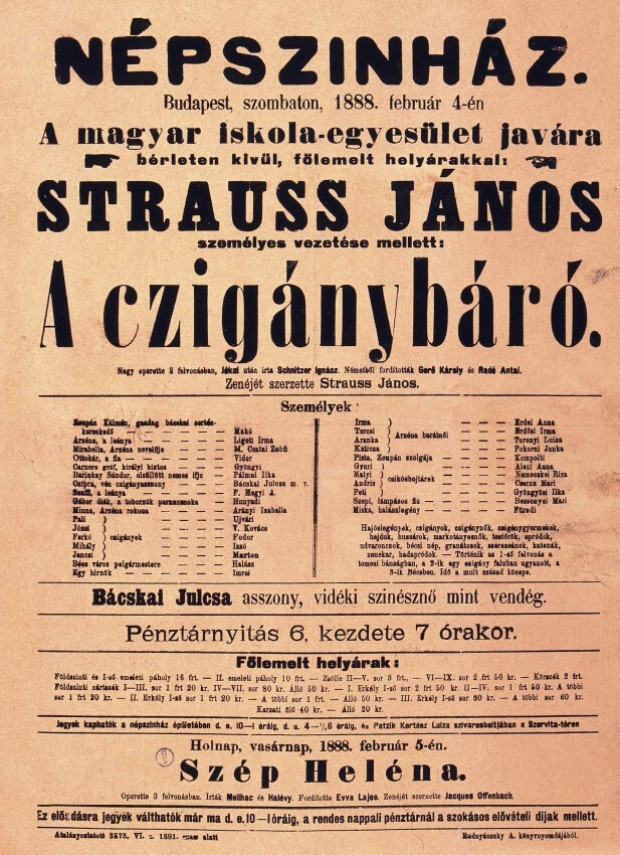

In light of all this, it is not surprising that Strauss’s work – as translated by Károly Gerő and Antal Radó – was also performed at Budapest’s Népszínház (Folk Theater) the year after its Viennese premiere. This was followed by a guest performance in 1888 with the composer himself conducting at the Népszínház.

The beginnings of operetta in Vienna

The Viennese variety of operetta, which emerged around 1860, drew on two main sources. On the one hand, there were the traditions of light musical theater in the imperial city, including works such as the folk plays [Volksstücke] and fairy farces [Zauberspiele] of Johann Nestroy and Ferdinand Raimund. On the other, there were the musical stage works of the French composer Jacques Offenbach, which had enjoyed unprecedented success throughout Europe. Offenbach’s pieces first appeared in Viennese theaters in 1858 and were performed with increasing frequency and regularity from 1860 onwards. It should be noted that this French composer used the diminutive term “operetta” [opérette], meaning “little opera” or “little work,” for those pieces of his which – due to administrative regulations – employed only two or three actors and did not exceed one act in length. In Vienna, however, the term “operetta” – which was already frequently employed to describe German singing plays [Singspiele] as early as the late eighteenth century – became a collective moniker for all kinds of cheerful musical pieces regardless of length or setting.

The Vienna premiere of Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld [Orphée aux enfers] provides a good example of how local theater traditions were connected to what was in vogue in Paris: the play was performed at the Carl-Theater with the director, Nestroy, playing Jupiter – the chief god – himself. However, it was not Nestroy who played the truly decisive role in introducing Offenbach’s works to Vienna, but rather Karl Treumann, an actor, director, and translator who had moved from Hamburg to Vienna and who played Pluto, king of the underworld, in the Viennese premiere of Orpheus. Treumann also performed in a number of other Offenbach pieces in addition to translating several of their librettos and directing more than one himself. The works were not usually performed with their original orchestration but were reorchestrated from piano scores by the theater’s conductor, Karl Binder.

Influenced by Parisian trends, local operettas were soon being written in Vienna by composers such as Franz von Suppé from Dalmatia, Ivan Zajc from Croatia, and – from the 1870s – Johann Strauss the Younger. Theater and music historians regard Suppé’s one-act work The Boarding School [Das Pensionat], which premiered in November 1860 at the Theater an der Wien, to be the first true Viennese operetta. Alongside the Carl-Theater, the Theater an der Wien was the other main venue for this genre in Vienna.

The combination of its cosmopolitan origins in Paris and the colorful cultural milieu of the multiethnic capital of the Habsburg monarchy rendered the cast and music of Viennese operettas quite diverse from the very beginning. The stage characters usually belonged to several different ethnicities, including Austrians, Hungarians, Serbs, Croats, Slovaks, Romanians, and Gypsies.

Among the musical pieces, one finds French-style, recurring verses called couplets and ensemble finales at the end of each act, reminiscent of Italian comic operas. There were also quite a few pieces with a dance-music motif, involving the waltz in particular, which had been commonplace in Austrian popular music for a long time but had attained European-wide popularity since the Congress of Vienna (1814).

With respect to Hungarian stage characters, we often encounter Hungarian-style verbunkos and csárdás dance music. For example, when Rosalinde, the female lead in Strauss’s The Bat [Die Fledermaus (1874)], appears at Prince Orlofsky’s ball in the second act disguised as a Hungarian countess, she performs a solo piece entitled “Csárdás,” whose slow-fast structure and syncopated cadences are comparable in all respects to Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies.

Operetta in Pest

Treumann, whose two brothers performed at German theaters in Buda and Pest – which at that time enjoyed larger audiences than the Hungarian theaters – played a pivotal role in the beginning of the operetta culture in the Hungarian capital. All indications suggest that Offenbach’s operettas were first performed in the Hungarian capital in German during Treumann’s guest performances in 1859 and 1860. As far as Hungarian-language performances are concerned, it would appear that Mihály Havi’s Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca) company took the lead, performing Offenbach’s one-act operetta The Wedding by Lantern-Light [Le mariage aux lanterns (1857)] in Brassó (Brasov) in October 1859 and then in Kolozsvár in December.

The translation of the genre into Hungarian came a little later in the capital, between 1860 and 1863, partly at the Nemzeti Színház, where the actor Kálmán Szerdahelyi spearheaded efforts, and partly thanks to György Molnár, who also visited Paris, and his stage company, which first performed at the Buda Nyári Színkör and then, from 1861, at the newly opened Buda Népszínház. In addition to Offenbach’s satirical works, Viennese pieces were also soon performed in the Hungarian capital. Although it is true that the Nemzeti Színház premiere of Suppé’s The Boarding School caused a minor outcry – at least that is what György Molnár claims in his memoirs, From Világos to Világos [Világostól Világosig].

The Wedding by Lantern-Light, which was the first Offenbach operetta performed in Hungary, has a pastoral setting. It is no coincidence that Hungarian theaters chose this particular work; light musical theater had its own unique local traditions in Hungary at the time, just as it had in Vienna, and since the 1840s, folk plays mostly in pastoral settings had been particularly popular – typically incorporating Hungarian folk songs and Gypsy music interludes. Above all, these works included Ede Szigligeti’s The Deserter [Szökött katona (1843)], Two Pistols [Két pisztoly (1844)], and The Horse Keeper [Csikós (1847)]; or, in the latter half of the century, Ferenc Csepreghy’s plays The Yellow Colt [A sárga csikó (1877)] and The Red Wallet [A piros bugyelláris (1878)]. Allaga Géza és Bényei István’s The Love Singer [A szerelmes kántor (1862)] was for the most part a cheerful folk play with folk song interludes rather than a true operetta. In any case, from around 1860 onwards, the two genres – operettas and folk plays – coexisted on the Hungarian stage and explains why the Hungarian variant of operetta became so folksy, with crying and rejoicing elements, and how the aptly named “operetta gypsy” – as coined by music historian András Batta – became one of its characteristic types.

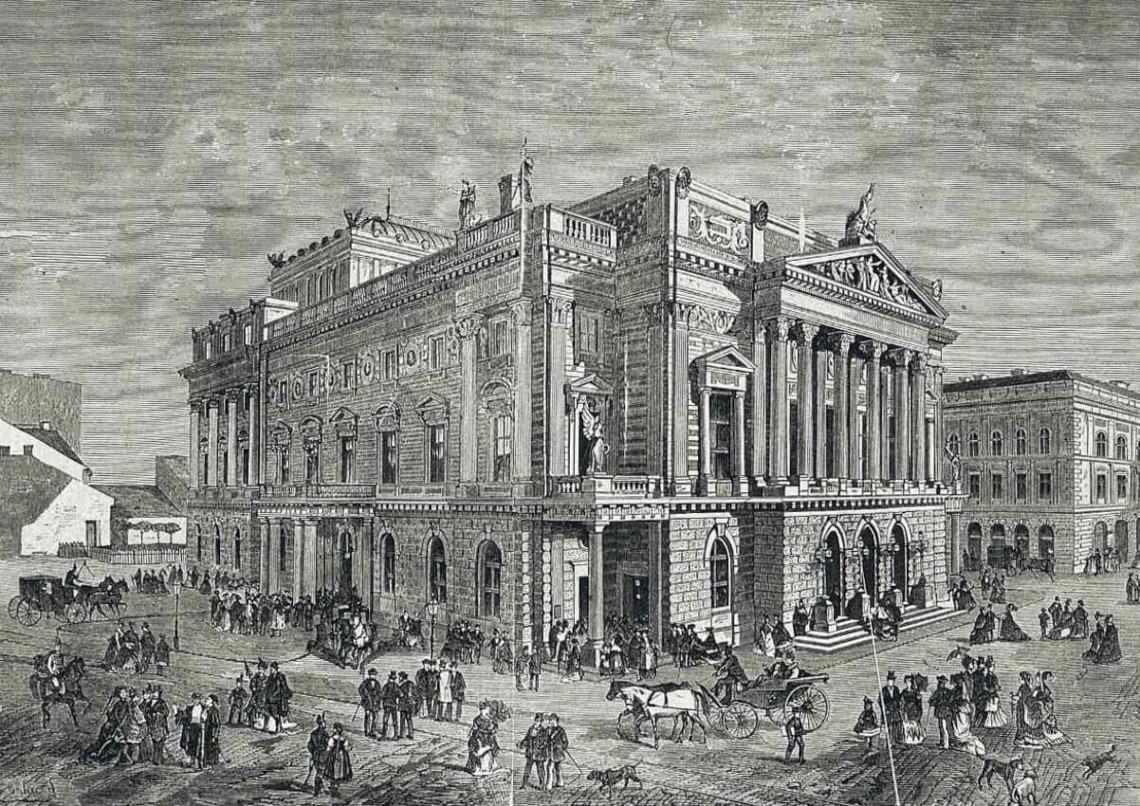

The new genre found a more permanent home in the Hungarian capital in 1875, following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise. It was then that the new Népszínház was completed in Pest, which operated until 1908 and whose building subsequently housed the Nemzeti Színház until its demolition in 1964. Although the Népszínház primarily set itself the task of developing a folk play repertoire, which they tried to expand with new plays by announcing commissions at certain intervals, operettas increasingly came to dominate its program as reflective of a more urban lifestyle. Even Lujza Blaha, the most popular folk theater prima donna of the era performed in both folk plays and operettas. In 1879, for example, she played the title role in Suppé’s highly successful operetta Boccaccio, or the Prince of Palermo [Boccaccio, oder Der Prinz von Palermo (1879)]. This male role had already been played earlier by female performer – Antoinie Link – at the Vienna premiere. It was a common practice at the Népszínház, however, to have roles originally intended for male singers to be transformed into “breeches roles,” where female actors performed in male clothing. In the 1888 program for the Strauss-conducted The Gypsy Baron, for example, Ilka Pálmay – another popular prima donna of the era – played the lead male role of Sándor Barinkay.

On the initiative of the Népszínház’s first director, Jenő Rákosi, the theater expanded its repertoire beyond the latest works from Paris, Vienna, and even London to include a number of original Hungarian operettas, with music composed by the institution’s conductors – Ferenc Puks, Elek Erkel (son of Ferenc Erkel, composer of the Hungarian national anthem, the “Himnusz”), Lajos Serly, and József Konti. The play The Lively Devil [Az eleven ördög (1884)] by the Warsaw-born Jewish composer Konti proved particularly successful. Although originally performed in German under the title Der kleine Vicomte [The Little Viscount] in Sopron in 1884, it gained nationwide popularity in its Hungarian translation. In addition to the capital, operetta also became beloved and popular in large provincial towns; József Bokor the Younger’s play The Little Coward [A kis alamuszi], for example, was first performed in Szabadka (Subotica) in 1892, before being included in the Népszínház program two years later, and eventually being performed at the Carl-Theater in Vienna in 1896 under the translated-German title Der kleine Duckmäuser.

Austro-Hungarian operetta at the turn of the century

However, the 1896 Vienna premiere of Bokor’s piece was rather the exception in the Hungarian repertoire in the years before 1900; it was only after the turn of the century that Hungarian operetta would become an internationally exportable genre. It was at this time that a new era of musical theater began, which – in contrast to the “golden age” of the nineteenth century – was referred to as the “silver age” of operetta. The beginning of this era is usually linked to the 1905 premiere of Ferenc (Franz) Lehár’s play The Merry Widow [A víg özvegy]. Lehár, who was born in the Hungarian town of Komárom (Komárno) in 1870 and studied music at the Prague Conservatory, began his career as a military conductor, like his father, and performed at a number of important garrison towns in the monarchy.

The military bands of Imperial Austria-Hungary were not simply brass bands, since as early as the 1850s, they also incorporated well-organized string sections. Thus, their members played an important role in civilian life as potential theater orchestra accompanists. Moreover, writing for various transposing woodwind and brass instruments required considerable talent; thus, Lehár’s experience as a military conductor contributed greatly to the virtuoso orchestration of his operettas.

Lehár’s stage works generally premiered at Viennese theaters: The Tinker [A drótostót (1902)] and Gypsy Love [A cigányszerelem (1910)] premiered at the Carl-Theater while The Merry Widow and The Count of Luxembourg [Luxemburg grófja (1909)] saw their first performances at the Theater an der Wien. It was at this time that we can rightly speak about Austro-Hungarian operetta as a genre, even if we know that the repertoire of the Viennese theaters soon appeared in Hungarian translation in Budapest as well. However, in many cases, it would be more correct to talk about adaptations than translations. Lehár’s play Viennese Women [Wiener Frauen (1902)] appeared on the program of the Városliget Színkör in Pest under the title Women of Pest [Pesti nők].

As with Lehár, Vienna and Budapest likewise played an equally important role in the career of Imre (Emmerich) Kálmán, another successful turn-of-the-century composer. Born in the Hungarian town of Siófok in 1882, Kálmán learned the basics of musical composition around 1900 at the Budapest Academy of Music, taking classes from the noted German music teacher Hans Koessler – just like his compatriots Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály. Between 1904 and 1908, he briefly tried his hand at journalism, regularly publishing music reviews in the Pesti Napló newspaper. However, his music for the Károly Bakonyi and Andor Gábor operetta The Tartar Invasion [Tatárjárás] was greeted with so much success at its 1908 premiere at the Vígszínház [Gaiety Theater] that it was performed the following year at Vienna’s Carl-Theater under the German title The Autumn Maneuvers [Ein Herbstmanöver] and eventually made its way to a Broadway theater under the title The Gay Hussars. Following this international success, the premieres of Kálmán’s works usually took place in Vienna, and such successful plays as The Gypsy Violinist [Der Zigeneurprimas/A cigányprímás (1912)] and The Gypsy Princess [Die Csárdásfürstin (1915)/A Csárdáskirálynő (1916)] – both of which premiered at the Johann Strauss theater – were no exception. After 1939, however – and this was unfortunately typical of the time – Kálmán was forced to emigrate, living in the United States during World War II before eventually dying in Paris in 1953.

Unlike Kálmán and Lehár, the career of the third successful turn-of-the-century operetta composer – Jenő Huszka – was entirely connected with Budapest. Like Kálmán, Huszka was a student of Koessler’s at the Budapest Academy of Music, although he spent part of his youth as a violinist with the Orchestre Lamoureux in Paris. He enjoyed his first big success with the operetta Prince Bob [Bob herceg (1902)], which was set in London. This was not surprising since British operettas were quite popular in Budapest around the turn of the century.

Besides the operetta melodies of Kálmán, Lehár and Huszka, Hungarian operetta prima donnas, such as Ilka Pálmay, Klára Küry, and Sári Fedák were no less popular in both imperial capitals. The turn of the century also saw the opening of private theaters specializing in operetta performances in the Hungarian capital, such as the Magyar Színház (1897) and the Király Színház (1903).

Sad operetta

It is particularly interesting to chart how the harsh historical experiences of World War I changed a once cheerful, entertaining genre to become bittersweet if not tragic in character. Or to put it another way: how did the genre that the Hungarian writer Dezső Kosztolányi once described as “sad operetta” on the pages of Színházi Élet in 1920 develop around this time?

Kosztolányi, who witnessed those times, perceived a direct connection between the passing of the old, peaceful world and the changing tastes of the theater audience. As he wrote at the time: “Operettas are becoming more serious and meaningful. This playful, lighthearted genre […] has undergone a subtle transformation in recent years, becoming imbued with substance, emotion, and sadness. Now there are already sad operettas as well. In fact, it seems only sad operettas are popular. […] Maybe the war caused this. So much suffering and grief has swept through the world that even in the operetta, although we welcome life, we do not shy away from the shadow of death, which has become a close acquaintance of ours in recent years.”

Alfred Maria Willner, Heinz Reichert, and Heinrich Berté’s play Three Little Girls marked an important turning point in this regard: its music could neither be considered new nor original in the year of its premiere. The work, which was first performed on January 15, 1916, at Vienna’s Raimund Theater – owned by the Hungarian Vilmos (Wilhelm) Karczag – is set in old, nineteenth-century Vienna. The hero of the story is a typical artistic figure of the 1820s – the musician Franz Schubert, with the musical score also compiled and orchestrated from his compositions.

The idea was not new: in 1864 the Vienna Carl-Theater already staged an operetta entitled Franz Schubert, with the libretto written by Hans Max and music by Franz von Suppé (supplemented by Schubert themes). But whereas Suppé’s Schubert work was performed only 15 times, Three Little Girls was a huge success in the midst of World War I, and not only in Vienna. It ran for 151 performances in a row at Budapest’s Vígszínház Theater, and this run did not cease at the end of May 1916, when Max Reinhardt’s troupe performed there as guests – the production was simply moved to the larger Népopera, which could accommodate many more theatergoers. The newspaper Színházi Élet noted that “the play is unprecedentedly popular; Schubert, the musical genius of a hundred years ago, is suddenly all the rage in Pest; people are singing and playing Schubert songs, humming and whistling everywhere, and those who haven’t seen it are pointed at. Anyone who has already seen it calls the besieged box office days in advance so that they can see it again.”

The plot of the play certainly exhausts our notion of “Biedermeier kitsch.” Schubert, in the operetta – played by opera singer Béla Környei at the Vígszínház premiere – is secretly in love with Hannerl – Médi in the Hungarian translation – one of three daughters of Tschöll, the court glassmaker. In the second act finale, the composer wishes to confess his love to Médi with the song “Impatience” [Türelmetlenség/Ungeduld] from Schubert’s song cycle The Fair Maid of the Mill [A szép molnárlány/Die schöne Müllerin (1823)], but in his shyness he asks his friend, the womanizer Baron Franz von Shober, to sing the song to the girl instead. Due to a tragic misunderstanding – in which Schober’s jealous lover, the opera singer Grisi, who is also romantically involved with the Danish ambassador, plays an important role – Médi interprets the song as a sign of Schober’s love and she ultimately offers him her hand, while the unhappy composer is forced to settle for platonic affection and remain true to his vocation, music. The mood of the operetta is quite bittersweet, and the penniless, unattractive, and shy Schubert is a tragicomic figure in his own right. In sum, although all three girls eventually find partners by the end of the play, the protagonist’s love remains unrequited, even though by the conventions then established in the monarchy, the operetta should have ended with the main characters marrying for love.

As we can see, operetta, which emerged as an international theatrical novelty in the 1860s and was one of the most successful joint cultural products of the Austro-Hungarian state around the turn of the century, became a field of nostalgic remembrance following the dissolution of the monarchy. As the example of the Three Little Girls shows, during the World War I years audiences had become particularly receptive to plays evoking memories of old Vienna. The case of The Gypsy Baron transcriptions mentioned at the beginning of this article also attest to the fact that even after 1918, those born in the former empire – such as Schönberg, Webern, or Dohnányi – could rightly draw on the nostalgic emotions awakened by the “Treasure Waltz.”

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)