On Good Friday, March 30, 1945, the Roman Catholic prelate Vilmos Apor was shot three times by a burst from a Soviet soldier’s submachine gun. He received mortal injuries to which he succumbed after three days of suffering. This charitable and socially conscious cleric did much to help the poor and those in difficult situations, both as a parish priest in the town of Gyula and later as the bishop of Győr. Born into an aristocratic family, he used his wealth, influence, and social position to help those in need. These efforts continued during the Second World War, as he offered asylum and shelter to the afflicted and interceded on behalf of those persecuted due to their origins. Because of this, he himself suffered persecution during the German occupation and then under Arrow Cross rule. Nor did he ignore the plight of those threatened by Soviet forces, providing them refuge in the basement of his bishop’s residence in Győr. In doing so, he protected women against the violent assaults being committed by Soviet troops. He was doing the same on that Good Friday in 1945. In standing up to the Soviet soldiers, he offered his own life to protect the vulnerable.

Life path

Vilmos Apor was born in the town of Segesvár (Sighișoara) on February 29, 1892. He attended secondary school with the Jesuits in Kalksburg and Kalocsa before continuing his theological training at the seminary in Innsbruck. Sigmund Waitz, the Auxiliary Bishop of Brixen, ordained him a priest in Nagyvárad on August 24, 1915. Shortly afterward, the Bishop of Nagyvárad, Miklós Széchenyi, appointed him chaplain in Gyula, where he served between August 31, 1915, and January 17, 1917. He later undertook pastoral duties on a hospital train as a field chaplain and was subsequently appointed prefect and professor of dogmatics at the seminary in Nagyvárad on July 1 that same year. Having served at the seminary for one year, Apor was appointed parish priest in Gyula, where he performed his offices from September 1, 1918, to March 1, 1941, taking over from János Lindberger, who had been appointed parish priest in Debrecen.

Vilmos Apor’s name first appeared on the list of government-approved candidates for higher ecclesiastical office in 1938 for the auxiliary and diocesan bishoprics of Veszprém and then in 1939 for the diocesan bishopric of Szombathely. On neither occasion was he selected.

When Bishop István Breyer of Győr died on September 28, 1940, leaving the diocesan bishopric vacant, the Papal Nuncio Angelo Rotto supported Apor’s candidacy. Pope Pius XII made his decision on January 19, 1941, in the Vatican, and the bull announcing Apor’s appointment was dated January 21, 1941. Vilmos Apor was consecrated as bishop on February 24, 1941, by Jusztinián Serédi, the Prince Primate of Hungary, assisted by Bishop Gyula Glattfelder of Csanád and Bishop Gyula Czapik of Veszprém, in the packed parish church of Gyula.

Thus, Vilmos Apor became the 72nd bishop of the Diocese of Győr, founded by Saint Stephen, and ninth in the line of those high ecclesiastics who were either born in the Transylvania or Várad dioceses or had been transferred from there to become bishops in Győr. Vilmos Apor assumed his episcopal seat at a very difficult time, on March 2, 1941. In his inaugural speech, he asked his priest to let love guide their work and to spare no effort in serving both the Church and their country. He urged the faithful to preserve and foster unity within the family – between the younger and older generations – nurture compassion for the poor, and to work together for the common good.

In defense of the weak

On March 28, 1945, Soviet forces reached Győr. The number of refugees seeking shelter in the Győr bishopric continued to grow until they numbered around 300 to 400 people and the cellar rooms were full to overflowing. The first Soviet soldiers entered the cellar of the bishop’s residence only after dark. Over the next few days, they dropped by the bishop’s residence more and more often. Bishop Apor would personally greet every Soviet soldier at the entrance to the cellar, and he did not sleep at all until that fateful Good Friday evening – despite the earnest entreaties of those around him to rest a little during the day. Instead he would respond, saying, “If something happens, I need to be awake.”

The Soviet soldiers conducted themselves in various ways when dealing with him. Some would kneel down before him and kiss his ring, but there were others who wanted to pull the ring off him or search him for weapons.

On the morning of March 29, Maundy (Holy) Thursday, German forces launched a heavy artillery barrage upon the bishop’s residence from their positions on the far bank of the Raab River, directly opposite the residence, after having blown up all the bridges across the river the previous day, including the bridge near the residence. The residence was also subjected to mortar fire that same day. The Germans used incendiary shells to set fire to the tower and roof of the cathedral basilica adjacent to the bishop’s residence as well as the tower of the nearby Carmelite church. The sight of the burning churches greatly distressed the bishop.

On Maundy Thursday, he recited his last Mass in the cellar. When Good Friday arrived, the bishop was unable to perform the usual ceremony and read the Passion of Jesus instead.

Once the fighting ended in Győr, Soviet troops roamed the city looking for Germans. Several parties looked into the cellar at the bishop’s residence; the bishop sensed the approaching danger. He sent two priests to the Soviet command located in the town hall for assistance, but their efforts were in vain. They were also unable to secure a military guard to be posted at the cellar door. Soviet soldiers began visiting the cellar more and more frequently and were becoming more vocal. The situation was becoming decidedly dangerous. Unfortunately, a qualified interpreter could not be found, so the task was performed by a doctor who spoke poor Slovak.

On Good Friday afternoon, Bishop Apor openly called upon those men present, and especially the doctor-translator, to assist him if he had to take resolute action because – as he said – “We all have to die sometime, so it is better for a man to sacrifice his life in times like these.” It was clear from his words that he intended to protect all those under his care, even at the cost of his own life. Young girls and females were disguised as elderly women to avoid the attention of Soviet soldiers.

A martyr’s death

Soviet soldiers searched the bishop’s cellar for watches and German soldiers. As they searched for watches on people’s wrists, they could see from their hands that some of the women were not as old as their faces suggested. They tore the scarves from some of the ladies’ heads and shouted: Nyet mamka, nyet mamka, babka, babka. They also discovered the food stores and the wine cellar. They left peacefully at that point, but some of the soldiers returned later that afternoon in an inebriated state. They asked for people to peel potatoes.

At the bishop's request, elderly men and women volunteered to peel potatoes, while the younger ones hid. However, the soldiers refused the applicants as kitchen help and insisted on the younger women.

Apor stopped the Soviet soldiers on the cellar steps and shouted, “Hinaus! Hinaus!” [Get out! Get out!], demanding that they leave. One Soviet soldier wanted to tear off Apor’s pectoral cross, but the bishop resisted. A scuffle ensued and gunshots rang out. Sándor Pálffy, the bishop’s seventeen-year-old nephew, jumped in front of his uncle and took three bullets. The bishop himself was hit three times: one grazed his forehead, a second penetrated his cassock and the cuff of his right sleeve, while the third – the fatal round – entered his abdomen. The bishop collapsed after being hit.

Upon arriving at the hospital, he was immediately operated on. Not a sound of discomfort escaped his lips, even though – according to medical experts – a serious wound to the stomach and intestines causes enormous pain, such as cannot be alleviated even with painkillers.

On the afternoon of April 2, 1945, on Easter Monday, the Bishop of Győr departed for the afterlife. Residents of the bombed-out city received the news with shock and dismay. This development dispelled any notion that the Soviet military leadership intended to protect or show leniency towards church officials or institutions. The hospital doctors, nurses, and staff accompanied the deceased pastor to the gate. There his priests took over and carried him towards Chapter Hill, overlooking the city.

Although Bishop Apor had passed away two days previously, his funeral would have to wait.

His body could not be laid out for viewing in the burned-out basilica, so it was placed in the Gothic chapel in the bishop’s residence, before Our Lady of Hungary. They wanted to lay him temporarily at rest in the crypt of the nearby Carmelite church, and Dr. Andor Weisz, a justice of the peace, even offered his own destined burial niche for this purpose. However, in the absence of a coffin, the funeral had to be postponed; the undertakers were no longer operating. Even so, a coffin fitting the tall, broad-shouldered ecclesiastic could not be found. The younger priests, however, undertook to find a carpenter. There was a master craftsman available in Újváros, on the other side of the Raab River, but the fleeing Germans had destroyed all the bridges. In the end, the coffin arrived by boat, although at some risk.

On Wednesday, April 4, 1945, the procession wended its way down from Chapter Hill to the Carmelite church. Its starkness rendered the mourning greater poignancy than any pomp may have imparted. The simple nature of the ceremony was no less so. The funeral ceremony was conducted by Abbot-Canon Miklós Pokorny, the vicar-general, and there were perhaps ten or twelve people in attendance. All this was a fitting testament to Vilmos Apor’s modest nature.

A reburial will not take place

The body of the martyred bishop remained resting in the Carmelite crypt. Already at the time of his death, plans were in place for the St. Ladislaus Chapel in the cathedral basilica to be his final resting place. The clergy and parish faithful, despite impoverishment occasioned by war, donated the enormous sum of 120,000 forints to cover the costs of the tomb protecting the deceased.

Three years later, the new Bishop of Győr, Kálman Papp, issued the following instructions for the martyr’s reburial: “On Tuesday, November 23, and Wednesday, November 24, 1948, at 10 a.m., all the bells of the diocese shall ring for a quarter of an hour. In this regard, I am pleased to announce to my right reverend priests and beloved faithful that the carved tombstone for Bishop Vilmos has been completed in the Chapel of St. Ladislaus, in the cathedral. I am gratefully appreciative for everyone’s helpful contributions, and I cordially invite my right reverend priests and the beloved faithful to the solemn funeral of Bishop Vilmos on Wednesday, the 24th of this month, starting at 10 a.m.

The reception of the body will take place on Tuesday, November 23, at 5 p.m., with a solemn service to be performed at the Dóczy Chapel in the bishop’s residence. The diocese’s clergy will hold a vigil around the coffin throughout the night. On Wednesday, November 24, at 10 a.m., we will accompany him to the cathedral, where, after the funeral mass and burial ceremony, he will be laid to rest in the tomb erected in the Chapel of St. Ladislaus until the resurrection.”

Many believers, priests, and others wishing to pay their respects were expected at the funeral, and the entire Hungarian episcopate, led by Cardinal József Mindszenty, announced its intention to participate. However, on November 20, the Diocesan Authority sent out a terse notice signed by Bishop Kálmán Papp: “I hereby inform you that the funeral for His Eminence Baron Vilmos Apor, Bishop of Győr, scheduled for November 23 and 24, has been cancelled.”

As it happened, on Saturday evening, November 20, representatives of the Ministry of the Interior and a colonel of the political police, who had brought the chief magistrate of Győr with them, appeared at the bishop’s residence and presented to the bishop the mayor’s decision prohibiting the exhumation. The reburial was halted, and the bishop was ordered to inform the invitees that the funeral would not take place because “the planned funeral of Vilmos Apor would harm the country’s foreign policy interests.”

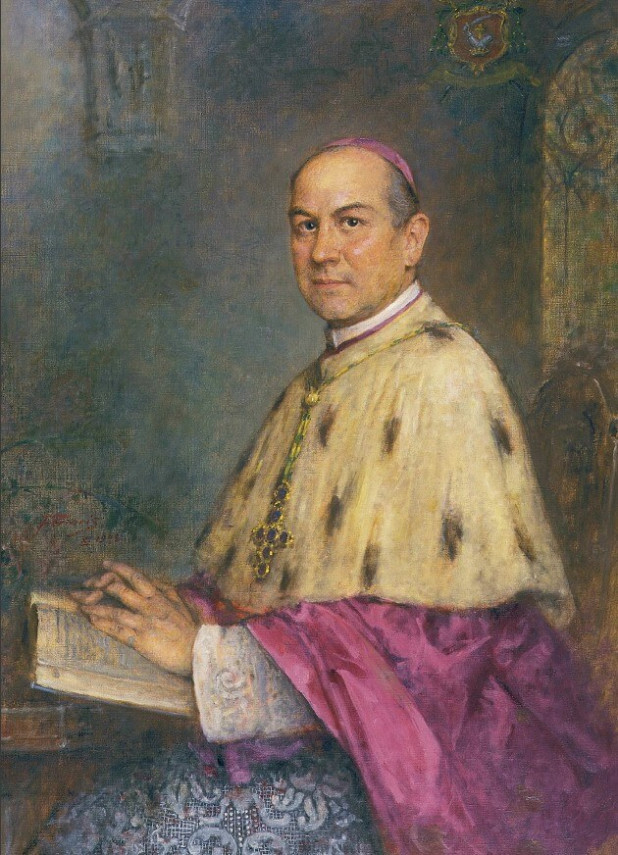

Vilmos Apor’s tomb in the cathedral basilica of Győr. The red marble tomb, carved by Sándor Farkas of Boldogfa, is framed by artwork by the Hungarian painter Eszter Mattioni.

Kálmán Papp’s energetic protests yielded no results. That same night, officials from the Ministry of the Interior informed the bishop and parish priests that the funeral would not be taking place. “The internal affairs authorities, which were already completely communist by this time, implemented extraordinary measures for the planned day of the reburial and funeral, fearing protests by believers outraged by the ban. Two hundred officers were sent to reinforce the Győr police, with the fire department also mobilized. Secret police surrounded the Carmelite church all night and mounted police patrolled the city center to prevent the “black reaction” from stealing the body. The roads leading to the Carmelite church and the cathedral were barricaded, and workers were instructed to break up the paving on the street connecting the two churches. Győr’s inhabitants, stuck outside the barricades, acknowledged the reality disguised behind the road work with a mixture of sarcastic remarks and scornful looks.”

They used equally crude and laughable measures to prevent the rural population from taking part in any possible Apor remembrance. That day, police checked the identity of everyone who approached Győr by train, car, bicycle, boat, or on foot. Only those who could prove they worked there were allowed to enter the city. The political police even banned the printing of the photographs of the tomb and memorial portraits of the deceased.

Epilogue

Forty years after these events, Hungarian and European public opinion ensured that the issue of Apor’s burial came to the fore once again as something that could no longer be delayed. However, the State Office for Church Affairs of the communist government still only allowed non-ceremonial burials. Thus, Vilmos Apor’s reburial in the cathedral sarcophagus on May 23, 1986, attended by a few aged canons, was more modest and Spartan than the first. After a lengthy wait, Vilmos Apor, the martyr bishop, was beatified by Pope John Paul II on November 9, 1997.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)