Numerous attempts have been made to encapsulate the conflict between Hungary and Austria in 1848 with a single word. Austrian and Russian accounts published after 1849 used the words revolution, rebellion, and uprising (Revolution, Rebellion, Aufstand, Insurrektion). Works published in Hungarian or German in Hungary between 1849 and 1867 also used the word revolution to describe the events (forradalom, Revolution). This was the term that the Hungarian historian Sándor Szilágyi (1827–1899) also used. The writer Zsigmond Kemény (1814–1875) did the same, although he also found room to criticize the extremist policies of the revolution’s leader, Lajos Kossuth, in his pamphlet Forradalom után [After the revolution].

While using the pejorative revolution, “official” Austrian works of the nineteenth century were most inclined to discuss the events as a sequence of military operations. Even so, they typically highlight only the summer and winter campaigns, i.e., the two most successful engagements from the Austrian perspective – one would be hard-pressed to search for accounts of the spring campaign among them.

But what do we mean by revolution? And was what had happened in March 1848 (or more specifically, on March 15) indeed a revolution? Did the participants know they were making a revolution? Did they even consider the events a revolution?

Changing terminology

The Hungarians and their supporters described an independence war, a national struggle, or a fight for freedom and avoided using the word revolution as much as possible. An exception is the work of Charles Louis Chassin and Dániel Irányi, published in France in 1859–1860, entitled A magyar forradalom politikai története 1847–1849 [The political history of the Hungarian revolution 1847–1849]. However, the word revolution did not carry as negative a connotation in France as it did in other countries on the continent; indeed, contemporary French national consciousness was clearly rooted in the period between 1789 and 1794. One pro-Austrian French historian, on the other hand, argued that it was a mistake to label the Hungarian events a revolution, as they were nothing more than a rebellion against legitimate authority, much like the seventeenth-century uprisings of the French nobility.

Lajos Kossuth, as head of the National Defence Committee and then as governor-president maintained parliamentary norms throughout. Despite the undoubted personal influence, Kossuth did not become a Hungarian Robespierre.

At the same time, it is telling that when Bishop Mihály Horváth (1809–1878), a minister in the Bertalan Szemere government of 1849, wrote on the events of 1848–1849, he did so in two separate works. His two-volume Huszonöt év Magyarország történetéből [Twenty-five years of the history of Hungary], published in 1864, covers the period between 1823 and 1848. The eighth book of this work, entitled “Az átalakulás forradalomszerű keresztülvitele” [The revolutionary implementation of the transformation], discusses the period from early March to mid-April 1848, that is, up to the arrival of the Batthyány government. His 1865 work, Magyarország függetlenségi harczának története 1848 és 1849-ben [The history of Hungary’s war of independence in 1848 and 1849], begins in April 1848 and ends in October 1849, with the surrender at Komárom and Austrian retaliation. In the preface to this later work, Horváth explained that what transpired in the spring of 1848 was the logical result and conclusion of the reform era, and that what followed was a radically different and independent series of events. In other words, there was no straight path between the events of March 15 and April 11, 1848, and the subsequent War of Independence.

Following the Austrian-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the term szabadságharc, which encompassed both self-defense and the fight for independence, came to the fore in the Hungarian lexicon. Popular historical publications, including works by Endre Vargyas, György Brankovics, and György Gracza, and the large illustrated album by the trio Sándor Bródy, Mór Jókai, and Viktor Rákosi, all used this term.

Meanwhile, the noted historian Marczali Henrik (1856–1940), in his exhaustive history of the modern era, denoted the events of the spring of 1848 in both Hungary and Austria as a revolution, while reserving the term szabadságharc for the period following the Serbian uprising, which broke out in the summer of 1848. In the ten-volume A magyar nemzet története [The history of the Hungarian nation], edited by Sándor Szilágyi and published during Hungary’s millennial celebrations, the historian Sándor Márki wrote a chronicle of the period under the title Az 1848/49-i évi szabadságharcz története [The history of the 1848/49 war of independence]. In doing so, he divided this period into three chapters: the first, covering the events from November 1847 to the beginning of October 1848, was entitled A demokrata királyság megalapítása [The founding of the democratic kingdom], with Márki awkwardly avoiding use of the word revolution in connection with the Hungarian events in the text. The following chapter, Az önvédelem harcza [The fight for self-defense], covered the period from October 1848 to the end of March 1849, while the period that followed was discussed in the final chapter, A függetlenségi harcz [The war of independence].

This semantic discussion may seem overly abstract and unproductive, but it highlights the fact that the two positions occupied the same narrative space not only in 1848-49 but also afterwards. The source point for the Hungarian perspective was (public) law. According to this, the constitution Hungary received in the spring of 1848 was one it was already entitled to under its own laws, and for which it later rightfully took up arms in its defense, first against the Serbs and Croats, then against the Imperial Austrian army, and finally against the Russians. The Austrian (or rather, Imperial) perspective, on the other hand, was that the Hungarian politicians had extorted special rights, taking advantage of the empire’s precarious situation, thereby endangering the unity of the empire. Furthermore, they later sought to break up the empire by demanding even more rights. On top of that, they also drove Hungary’s national minorities away from them with their repressive policies. Austria did nothing more than defend the empire against a rebellion that threatened its continuance. Conspiracy theories also emerged on both sides. The Hungarians explained the outbreak of armed conflict on a long-prepared, joint plan of action on the part of the court camarilla, the imperial military clique, and national minorities. The Austrians, on the other hand, blamed the escalation of the conflict on a conspiracy between Kossuth and the radicals and European revolutionaries.

From the Hungarian perspective, the situation that had developed in April 1848 could only have been changed by the joint will of both parties, through negotiations. From the imperial perspective, however, the interests of the empire were paramount. If the other party to a conflict threatened this interest, the leaders of the empire had not only the right but also the duty to seek unilateral, even violent, correction. These two perspectives stemmed from different systems and structures. Prior to 1848, Hungary did not have an independent army or foreign missions, and it was not free to manage its own financial and commercial affairs. It was only through a lawful, legal settlement that the Hungarian side could change the nation’s position. Yet, from a constitutional perspective, it was in a more favorable position than the imperial leadership. The latter, however, had much more effective and persuasive arguments than the tools of constitutional law. Nevertheless, it was sometimes pointless to employ these to resolve political conflicts or to rule in their own favor if the Hungarian side were unable to legally accept the results. Hungary’s independence – i.e., recognition that its political system differed from that of Austria’s hereditary provinces – had been proclaimed law since 1790. And while in practice, the Hungarian side had been unable to enforce this independence within the context of the empire, the empire’s leaders, in turn, were unable to legally nullify this Hungarian claim.

Serb-Hungarian fighting in the then-southern region of Hungary (Délvidék) in the summer of 1848. As in France after 1792, units of the same army were often pitted against one another, with ethnic cleansing on the part of the Serbs a common occurrence.

Interestingly, the Hungarian social scientist Ervin Szabó (1877–1918), who criticized Hungarian liberal historiography’s portrayal of 1848 and attempted a new interpretation of the events, did not emphasize the revolutionary aspects of 1848 in his works but rather questioned the revolutionary nature of the events themselves. In his opinion, the events of 1848–1849 differed little from the seventeenth-century struggles for independence, and that the leading nobility in the later period had as little interest in the lower classes as their predecessors had two centuries earlier. Even when it came to the emancipation of the serfs, Szabó still found grounds for criticism and even fundamentally doubted the liberal thesis that the Hungarian nobility, in making its proclamation, had been motivated by its generosity and by the “logic of the times,” i.e., the recognition of the inevitability of emancipation.

By all accounts, the joint notion of “revolution and szabadságharc” that is taken for granted today first appeared in the spiritual-historical synthesis undertaken in the Horthy era, on the pages of Magyar történet [Hungarian history] written and edited by Bálint Hóman (1885–1951) and Gyula Szekfű (1883–1955). It was under this appellation that Szekfű presented the sequence of events that unfolded between the “conservative reform” following the 1844 parliament and the October 1849 reprisals. However, it is unclear from the text what Szekfű regarded to be a revolution or what he considered revolutionary in the sequence of events. His brief account of March 15, 1848 – a total of twelve lines – was placed in a chapter entitled “A pesti radikális mozgalmak” [The radical movements of Pest], positioned chronologically after the April laws, and in a way that practically cast doubt on whether the Pest revolution had any effect on the victory of the legislative transformation of the old feudal estates into a democratic representative parliament and the sanctification of the April laws.

Following 1945, and especially after the centenary of 1848, this double appellation of “revolution and szabadságharc” became widespread. It was under this title that the Hungarian Communist Party published a centennial volume reflecting its version of 1848, as was the relevant volume (written by a convicted participant of the 1956 revolution) of the series Képes történelem [Illustrated history] intended for younger readers in the 1960s. The combination was also used with various attendant adjectives (bourgeois revolution, national szabadságharc) in official summaries, not to mention textbooks.

The lynching of Baron Franz Philipp von Lamberg(1791–1848), field marshal and chief of staff of the imperial and royal forces in Hungary, appointed commander-in-chief in Pest on September 28, 1848. Many feared the bloody incident would usher in a showdown with the moderates in Hungary. At the same time, the House of Representatives condemned the incident and ordered an investigation into the matter.

This phrase was later separated into two separate words – revolution or szabadságharc – when describing the events of 1848–49. In 1979, István Deák, a Hungarian historian living in the United States, termed the sequence of events a “lawful revolution”; however, when the work was published in Hungary in Hungarian translation four years later, it was not issued under this title, but under the original English subtitle of the work – Kossuth Lajos és a magyarok 1848–49-ben [Lajos Kossuth and the Hungarians in 1848–49] – lest anyone confuse it with another lawful revolution. Deák also nuanced the picture by using the term civil war; however, he did not apply this term to the armed conflict between Austria and Hungary, but rather to the one between the Hungarians and the nationalities within Hungary.

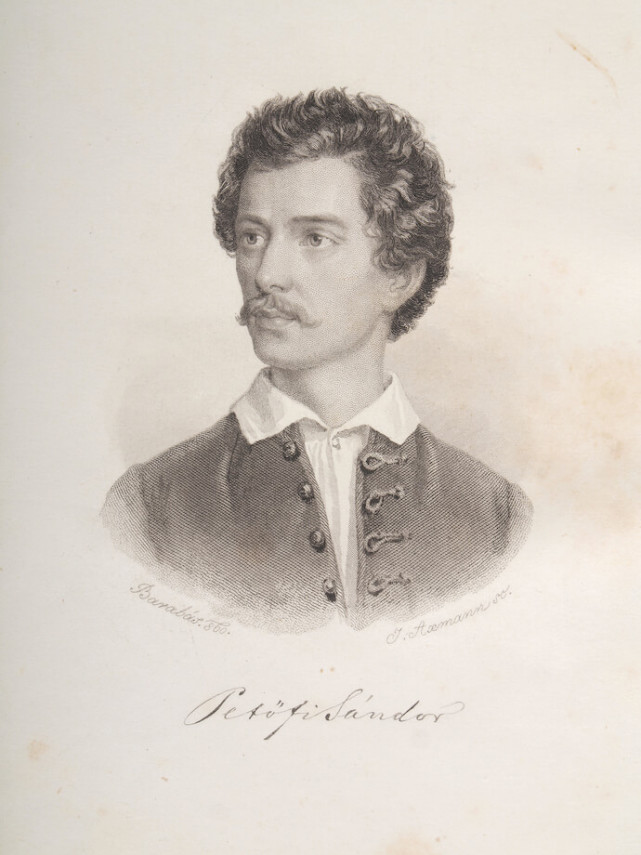

Pest and Pozsony

The situation regarding March 15, 1848, is quite clear. The events of spring 1848, especially those that took place in Pest, were already being called a revolution in works published in the spring of 1848. Sándor Petőfi (1823–1849), the leader of the Revolution in Pest, wrote to the poet and writer János Arany (1817–1882) on March 21: “It’s a revolution, my friend, so you can imagine how much in my element I am! … Yet many would like to deny this name to our movement, and why? – Because blood hasn’t flowed. But that is just the glory of the thing; it doesn’t change matters at all. I consider any violent transformation to be a revolution, and we have indeed achieved freedom of the press and Stancsics’s [Mihály Táncsics] release by force. The fact that there was no resistance only proves that the enemy was either fully aware of his pitiful weakness or was too cowardly to attack us. Hah, if you could have seen when the deputation from the comité du salut public [Committee of Public Safety] made their appearance, accompanied by thousands and thousands with their demands, how pale the dignified Viceregal Council (Helytartótanács) became and how they trembled!” Thus, Petőfi regarded a forceful transformation to be a revolution, one that needn’t be a bloody transformation at the same time.

In this respect, the revolution in Buda and Pest was indeed almost without precedent in contemporary Europe. The revolutions between January and March 1848, whether in Palermo, Naples, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, or Milan, began everywhere with mass demonstrations, armed uprisings, and clashes between revolutionaries or insurgents and the army guarding the old order, attaining a state of equilibrium or revolutionary consolidation only later on – if at all. The main demand everywhere was constitutionalism – except perhaps in Munich, where they demanded the departure of the king’s mistress. In France, the king and prime minister were forced to flee; in Austria, the same befell the chancellor Metternich while the imperial army was expelled from Milan. “In comparison,” the main achievement of the Pest revolution was the proclamation of freedom of the press and the release of a political prisoner under investigation – on the surety of the Pest county Vice Lord-Lieutenant, Pál Nyáry.

Sándor Petőfi immersed himself in

the study of the French Revolution.

Events in Hungary may have taken this route because the processes of “revolution” and consolidation had been proceeding alongside one another, reinforcing each other, from the very beginning. The Pest revolution essentially arose out of – and took on a life of its own – a nationwide signature campaign aimed at supporting Kossuth’s address to the Hungarian parliament of March 3, 1848, and broke out on the very day when the delegation from the Hungarian parliament left Pozsony (Bratislava) for Vienna in order to have the monarch and government of the Habsburg Empire assent to their petition formulating Kossuth’s demands.

Both the Pest Revolution and the adoption of the petition were impelled by the Vienna Revolution that broke out on March 13. However, Pest would have meant nothing with Pozsony, as the political center of the country at that time was not merely Pest but Pozsony as well, for it was in Pozsony that the Hungarian parliament, which could formulate and legislate Pest’s demands, sat. Pozsony, on the other hand, would have meant nothing without Pest, for if there were no (revolutionary) masses standing behind the transformation, the imperial leadership in Vienna could have taken command of the situation and dragged out discussions until a favorable change had ensued.

This sort of—at times spontaneous, at times conscious—cooperation and mutual reinforcement determined the events of March–April 1848. Without news of the Pest Revolution, the appointment of Lajos Batthyány as prime minister on March 17 and the acceptance – at least in principle – of the demands set out in the March 3 petition would not have taken place. Although the movements that flared up from time to time in Pest (and the provinces) were able to compel the court in Vienna to give way on the issues of emancipation, the realization of independence, and the competencies of a responsible Hungarian government, they could not have accomplished the civil transformation on their own – for this, the Pozsony parliament was required.

The Pest Revolution created its own governing organizations – the Pest City and the Pest County Committees of Public Safety (Petőfi bestowed the former with the French name for the Committee of Public Safety of the French Revolutionary Convention). But these organizations were not in competition with Pozsony – even if on certain issues they represented a more radical position than that taken in parliament or by the government of the day. Pest essentially made itself subordinate to Pozsony, and when on March 23, Lajos Batthyány named the prospective members of the government and together with the palatine appointed the members of the provisional council of ministers (the future Minister of the Interior Bertalan Szemere, the future Minister of Agriculture, Trade, and Industry Gábor Klauzál, who was in the capital, and Ferenc Pulszky, who had returned to the capital), the potential for conflict had practically disappeared – if only because Klauzál was also a member of the then-current Pest Committee of Public Safety.

Thus, Pest did not become such a seething revolutionary capital as Paris was between 1789 and 1794. This was also observed in Pozsony, and it was not by chance that Kossuth said the following on March 19 when receiving a delegation from the University of Pest: “I recognize the inhabitants of Budapest as inexpressibly important in this homeland and consider Budapest the heart of the country, but I shall never recognize it as its master. This nation has freedom, and every member therein wants to be free, and this word ‘nation’ cannot be expropriated by any one caste or any one city; the 15 million Hungarians in their entirety comprise the homeland and the nation. Thus, for my part, I was gratified to learn when amid the upheavals that the worthy inhabitants of the city of Budapest shared the same sentiment that inspired us when we spoke before the royal throne, that is, that alongside [the emperor’s] loyalty to the royal throne, I hope he also shares the sentiment that the nation alone is responsible for deciding the fate of the nation, and that he also shares the sentiment that this nation is so strong in its sense of rights, vocation, and destiny that it can crush anyone who believes otherwise.” And to one of the members of the delegation, Pál Vasvári – according to Count István Széchenyi's diary – he expressly told him that “whoever does not obey in Pest will be hanged!”

A scene from the siege of Fehértemplom, August 19, 1848. The atrocities of the civil war in southern Hungary were reminiscent of the brutal actions in the Vendée during the French Revolution.

Overall, we can thus rightly refer to what happened as a revolution because truly revolutionary changes took place, partly against the backdrop of revolutionary disturbances, mass movements, and demonstrations. The country gained an independent, responsible government, and thus for the first time since the defeat of Mohács in 1526, the most important decisions affecting the country’s destiny could be made within the country’s capital – and not originate outside its borders.

However, changes were not limited to the means of exercising power. It was at this time also that the country made the transition from a feudal system to a civil society. The majority of the previously emancipated serfs became freehold peasants of the land they cultivated. Although the revolution did not bestow property rights upon everyone, the declaration of the principle of equality before the law was one of the most important civil liberties. The sharing of public burdens and the introduction of census suffrage, one based on wealth and not social position, and popular representation all indicated that Hungary intended to pursue the path of social development already known in Western Europe, albeit with some delay.

The palace revolution

Kossuth, however, emphasized throughout his life that what happened in the spring of 1848 was not a revolution. Like other members of the Hungarian political elite, the youthful Kossuth studied the history of the French Revolution and even compiled a chronological account of it, and yet – like other members of the Hungarian liberal elite – he did not consider the events of 1789–1794 as a template to follow. In 1847, when Count Széchenyi, in his work Politikai programm-töredékek [Fragments of a political program], accused Kossuth of inciting revolution, the latter wrote a response that was banned by the censors: “History has taught me that the day of revolutions is often followed by the long night of servitude. The only weapon that can be relied upon is despair, and despair is only granted to those who have nothing left to lose. Thank God we still have it.”

It is characteristic that in Kossuth’s documents from between April and June 1848, he did not express the word revolution in connection with the Hungarian events of that spring. On July 1, when reporting to the representatives of the parliament, he stated: “Responsible government, having been established in Hungary, is enthusiastically supported by all the Hungarian legal authorities, and thus we have been able to reach our goal without the dangers of revolution, while other peoples, lacking constitutional inclinations, are hardly capable of shaking off the withering shackles of absolutism in such a restrained manner. – Party feuds have come to an end, and one Hungarian sincerely shakes the hand of another. – We have passed from revolution to a constitutional life without renouncing the principles for which we have fought since the dawn of our lives; we have brought order to freedom but have not sacrificed our principles for the sake of order. We have ensured that the strength of the motherland has remained unchanged.” In a major speech on July 11, he emphasized the falsity of the claim that “Hungary would have wrested its rights and freedoms from the prince [the emperor] through some coup or revolution.”

Even as late as February 1849, he stated that “the laws of 1848 were not revolutionary laws, nor did they grant the nation any new rights; they merely altered the structure of government administration, appointing ministers in place of the Viceregal Council, which itself was not an ancient institution, as a similar change had already occurred when that Council was first established.”

In addition, when proposing the Declaration of Independence and dethronement of the Habsburgs on April 14, 1849, he also explained, “It is my firm belief that the laws of 1848 in Hungary were not the offspring of a revolution. The Hungarian nation did not embark upon revolution with the laws of 1848; they were nothing more than the confirmation of those rights which on paper and in the oath of kings and in the agreements made with them were always ours before God and the world – if the oath of kings were more than an empty promise.” In the Declaration of Independence itself, he emphasized that “although, as a result of the troubles caused by the February French Revolution, almost every province in the Austrian Empire was seized by revolution and the dynasty was completely helpless, the loyal Hungarian nation did not try to take advantage of this situation by gaining more and more rights for itself at the expense of the king but was content with securing its national freedom, autonomy, and independence by means of a governmental system based on ministerial responsibility, against repeated breaches of the faith on the part of the crown.”

Later, during a lecture in England in 1858, he also stated: “Meanwhile, the Austrian House [i.e. the Habsburgs], from the moment it openly embarked upon the path of violence and revolution against Hungary, openly proclaimed its intention of assimilation on several occasions.”

Thus, Kossuth did not consider everything that happened on the Hungarian side between March 1848 and April 14, 1849 a revolution; rather, he saw it partly as a legitimate transformation and partly also as a legitimate self-defense struggle defending the achievements of this legitimate transformation. After April 14, however, both Kossuth and members of the newly-formed Bertalan Szemere government used the word revolution to describe the new period that began with the Declaration of Independence and the dethronement. In the parliamentary debate on the powers of the governor-president on April 22, he declared: “If now, when we are living in revolutionary times, they want us to save the country within the confines of Werbőczy’s laws, then I will certainly not accept this responsibility.” We may also adduce Kossuth’s proclamation issued on June 28, 1849, calling for a general uprising, which stated: “This virtue, this patriotic loyalty – this is the freedom-loving revolution.” At the same time, emphasizing the difference with the French Revolution, he explained that “the revolution of the Hungarian nation has avoided all the monsters of terrorism, and our way of fighting pays homage to the divine principles of civilization and humanity.”

He provided his most detailed explanation of the word revolution and his interpretation of the events in Hungary as a revolution in the aforementioned lecture delivered in England in 1858:

“There was indeed a revolution in Hungary in 1848, but it was not us Hungarians who initiated it but rather the Viennese court. It was the ruling house which—with royal sanction—used armed force to attack the constitutionally established, legal state; we assumed a defensive position against this attack, alongside the law.

I am not saying this as if I would like to absolve myself of the title of revolutionary. I believe and consider revolution to be a sacred right of peoples, but at the same time I regard it as a last resort, one that a people are only allowed to have recourse to when there is no other means to recover or to protect their national existence or their rights, or when an existing system stands in the way of the free development of their happiness to such an extent that the sacred interests of the nation demand its removal whatever the cost.

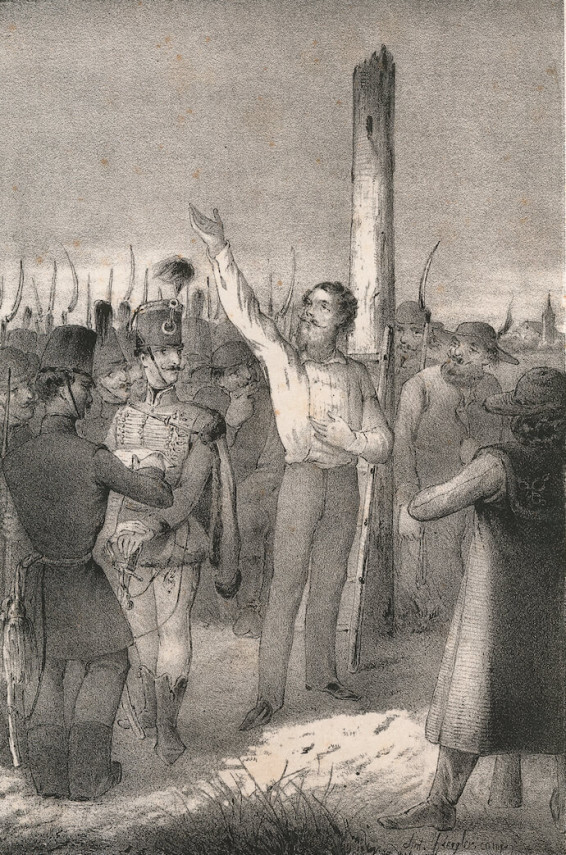

The execution of Count Ödön Zichy (1809–1848), the former Lord Lieutenant (főispán) of Fejér County, on Csepel Island, near Budapest, on September 30, 1848. The count was sentenced to death by a military tribunal in accordance with legal procedures.

Starting from this point of view, I openly confess that I both want and desire revolution. I will never play lightly with the blood of my nation and will make conscientious efforts to determine the prospects for success. But if the merciful and just God offers an encouraging opportunity with a prospect of success, I will – faithfully sharing in the danger – pursue every means possible to ensure that the banner of revolution, which demands the restoration of law and freedom, will fly high in the hands of my people. May God help me, but this is my resolute intention, and it is my intention for, as circumstances stand, it is only through revolution that my nation can regain the freedom and independence it has been deprived of, against both divine and human justice and despite laws, decrees, and treaties.

This is the situation now, but it was not like that in the spring of 1848. Then, we had no intention of making a revolution; then we only wanted reforms and we carried them out through constitutional means with the blessing of the king.”

Similarities and differences

Was the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-1849 comparable to the French Revolution of 1789-1794? Contemporaries were well aware of the history of the French Revolution. “For years, the history of the French Revolution was almost my exclusive reading, it was my morning and evening prayer, my daily bread even, this new gospel of the world in which the second Redeemer of humankind – freedom – proclaims its words,” wrote Petőfi in the spring of 1848. “Every word, every letter of the revolution was etched in my heart, and there the dead letters were reawakened, but being too constricted a space for those come to life, they ranted and raged within me.”

However, enthusiasm for the French Revolution was by no means universal. In fact, most contemporaries were downright terrified that what had happened in France in 1789, and especially between 1792 and 1794, might be repeated in Hungary. However, extreme revolutionary manifestations, as occurred in France, were essentially avoided. In the 1930s, the renowned communist ideologue József Révai tried to find similarities between the two series of events, but closer examination revealed greater differences. Significantly, the legal situation in Hungary remained the same after April 11, 1848, whereas France experienced a succession of constitutions between 1791 and 1794. This alone provided greater stability to the system in Hungary.

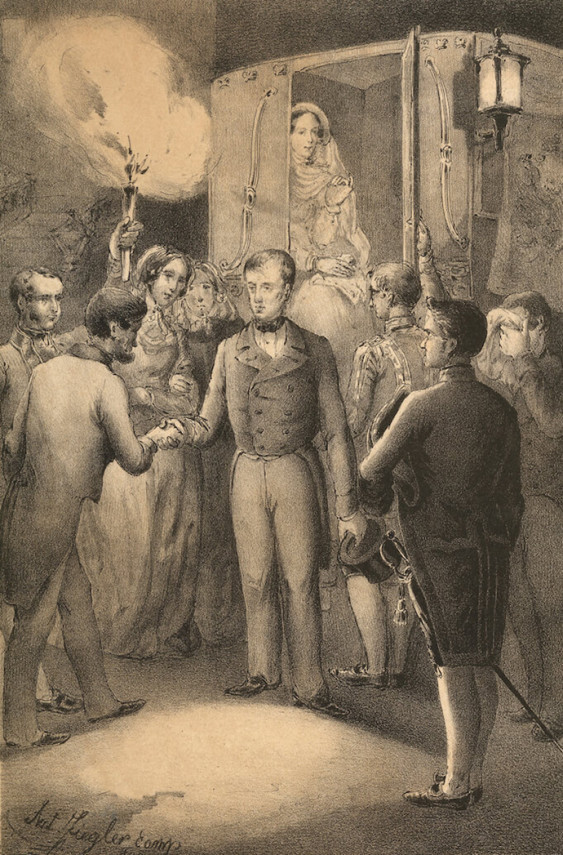

Louis XVI made an unsuccessful attempt to flee revolutionary Paris in June 1791. The Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I was more successful, arriving in Innsbruck in Tyrol with his entire court in May 1848, whence he would not return to Vienna until August.

Unlike in France, a republic was not proclaimed in Hungary. There were some voices in Pest that spoke in favor of a republic in the spring of 1848, when the imperial court was obstructing ratification of the law on an independent responsible ministry, but they lacked sufficient support. Bertalan Szemere (1812–1869), who supported the idea of a republic even before 1848, described his program as revolutionary, republican, and democratic in his acceptance speech as prime minister on May 2, 1849. Nevertheless, a republic was never proclaimed even if the emerging system did resemble a republic more than a constitutional monarchy.

No revolutionary-type provisional government emerged in Hungary, one that subsumed the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, as occurred with the Committee of Public Safety in France. The Committee of National Defense of the House of Representatives was always under the control of parliament while the specialized ministries – led by state secretaries – were always functioning, and despite Kossuth’s undoubted personal authority, he never possessed the unlimited and unchecked power wielded by Robespierre.

There was no revolutionary terror in Hungary, with its characteristic extremes and excesses. In his circular letter to Hungarian diplomatic agents abroad, the so-called Vidin Letter, sent a month after the defeat, Kossuth reflected on the differences between the French in 1789 and the Hungarians in 1848-1849 with a mixture of pride and sadness: “The glory is over; it was a bright meteor, but it has been extinguished. I was able to defend my nation against a foreign enemy but not against betrayal. Perhaps if I had been a Robespierre, but I could not be that, nor did I want to. Yet even in my unspeakable misfortune, I am edified in the knowledge that my hands are free from blood.”

There were no bloody confrontations among the revolution’s freedom fighters. Those deputies who refused to follow the parliament to Debrecen were not proscribed; at most, they were considered to have resigned after a long and complicated verification process. Although László Madarász, the “police minister,” who disgraced himself in the so-called diamond trial, was fond of mentioning the guillotine, not one of Kossuth’s opponents was imprisoned or executed.

In the end, the Hungarian events resulted in neither a military dictatorship nor one-man rule, as in France. Although General Artúr Görgei (1818–1916) was often accused of such ambitions, he expressly informed Kossuth’s opponents during negotiations in Debrecen that he had no intention of assuming executive power even if Kossuth were to be removed.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)