Of all the several waves of Hungarian political émigrés, the most significant group was undoubtedly that formed by those who departed abroad after the defeat of the 1848-49 War of Independence and named after their supreme political leader, Lajos Kossuth. The total number of Kossuth émigrés, that is, those who emigrated after the war, was around 6000 to 6500 during the period from 1849 to 1867, although most only spent a few weeks abroad. In terms of numbers, this is a drop in the bucket in comparison with the wave of émigrés after 1945 or 1956; nevertheless, these few emigrants were frequent participants in and sometimes shapers of contemporary European politics.

Three Hungarian refugees in Italy – from left to right: Ferenc Kossuth, Lajos Tivadar Kossuth, and Colonel Dániel Ihász. Of Kossuth’s two sons, Tivadar Lajos did not return home after 1867 and became an Italian citizen. Colonel Dániel Ihász also stayed in Italy but remained a loyal colleague of Kossuth until his death in 1881

The Hungarian War of Independence was crushed by the combined forces of Austria and Russia in August 1849. First, the forces in the field surrendered, and then the garrisons of the castles and fortresses. Surrender was unconditional, with the exception of the Komárom fortress, whose terms of surrender included the provision that anyone wishing to travel abroad within 30 days could receive the requisite travel documents.

Fate of the exiles

Due to the changed domestic circumstances, Hungarian diplomatic agents who had been sent abroad to the countries of Southern and Western Europe became émigrés. Such personages included Count László Teleki and Frigyes Szarvady in France, Ferenc Pulszky in the United Kingdom, Count Gyula Andrássy in the Ottoman Empire, and László Szalay in Switzerland. Although none of these figures were officially recognized as diplomats, they were not harassed by the authorities; on the contrary, given their extensive social connections, they had some political influence on local public opinion.

They were joined by those Hungarians who had defected from the Habsburg Italian Imperial-Royal Army and had participated or intended to participate in the struggle for Italian unity. Indeed, István Türr, who established the Hungarian Legion in Piedmont, soon became one of the leading figures among the émigrés.

However, the largest wave of émigrés entered Ottoman territory at Orsova, on the Danube, between August 13 and 23, 1849. The Turkish authorities gathered, disarmed, and dispatched them to Vidin, in present-day Bulgaria, where attempts were made to supply them with provisions. Although the higher-ranking refugees were afforded relatively good conditions, many complaints arose among the lower orders, officers, and ordinary civilian refugees regarding their treatment.

The number of refugees who fled to Ottoman territory – excluding members of the Polish and Italian Legions – was approximately 3,700–3,800 people. On September 9, the first reports arrived that the Austrian and Russian ambassadors were firmly demanding that the Porte extradite the Hungarian and Polish refugees. The Turkish authorities, the Polish agents in Istanbul, and even Count Gyula Andrássy, Kossuth’s representative there, wrote that it would be most advisable for the Hungarian and Polish refugees to convert to Islam, because the Sultan would then assuredly not hand them over to the Russians and Austrians.

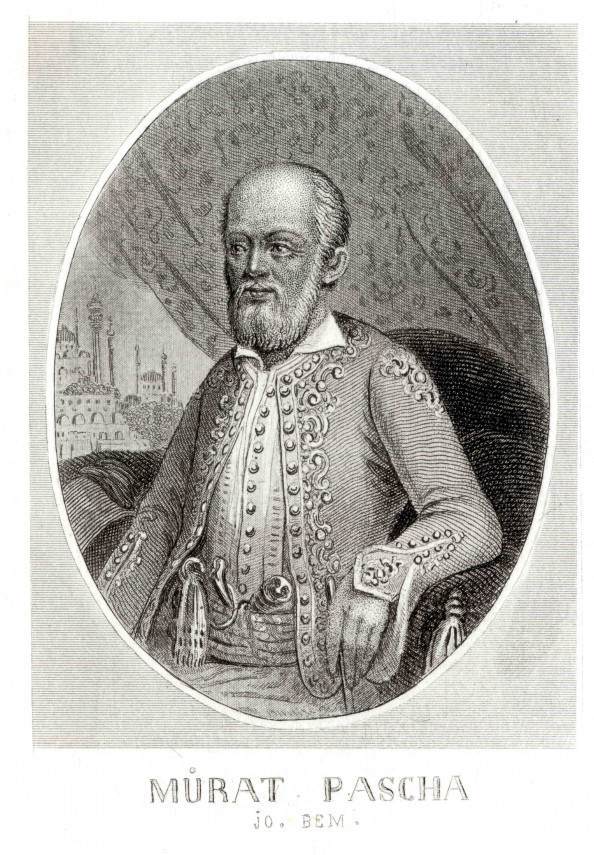

Kossuth resolutely forbade such conversion, not for religious or moral concerns, but for political ones. He was of the opinion that such a conversion would be no defense at all, for if Russia and Austria were to threaten war, it was doubtful the Ottomans would protect the converts. Some of the émigrés, however – including several high-ranking soldiers – believed this would allow them to demonstrate their military skills once again in an impending Turkish-Austrian war. In the end, some 267 refugees converted to Islam.

Meanwhile, the Turkish side acceded that Lieutenant General Franz Hauslab of the Imperial Austrian Army would visit the Vidin refugee camp in October to encourage those residing there to return home. Most of the roughly 5,500 refugees had had their fill of Turkish hospitality, and by the end of October, at least 3,156 people – including about 2,800 Hungarians – had decided to return. This reduced the number of Hungarians to less than 1,000, whereupon the Turkish authorities removed them from Vidin further east to Shumla (Shumen).

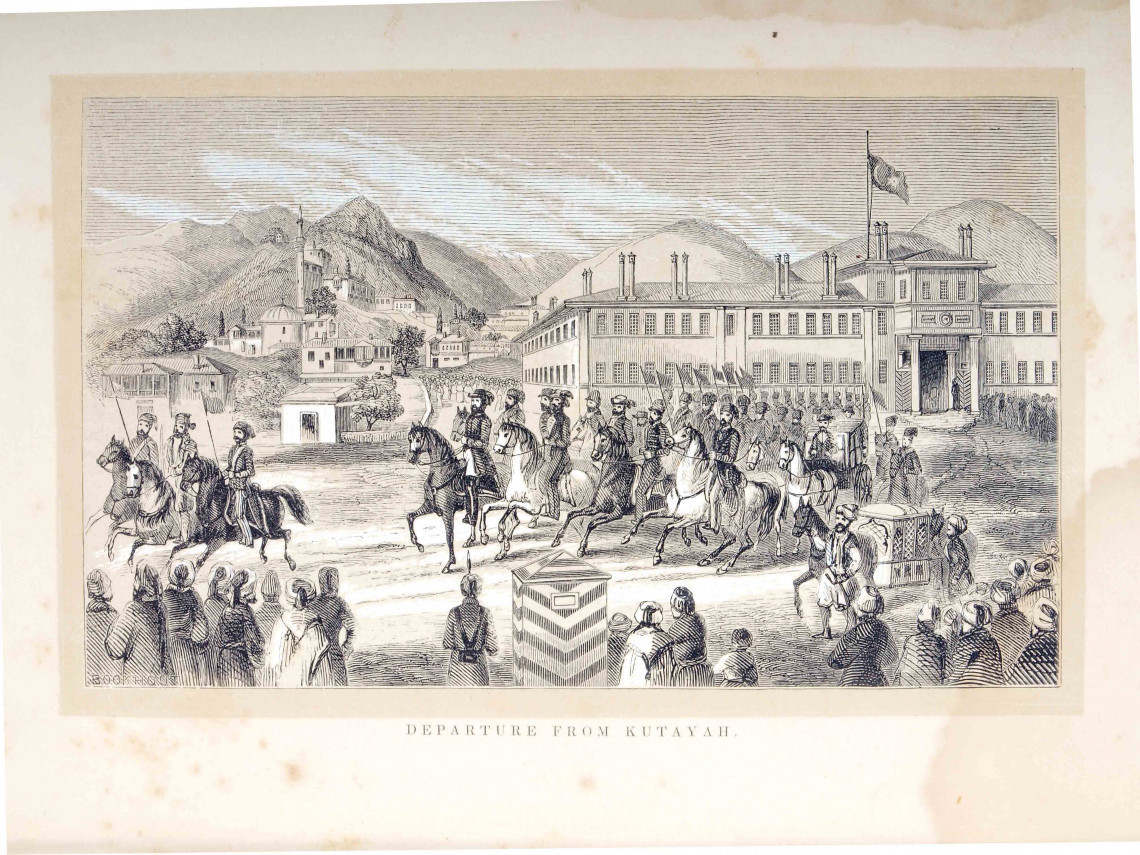

Kossuth in Kütahya

Their stay in Shumla lasted until February 15, 1850, by which time the number of Hungarians had dwindled to 492. The Porte, meanwhile, was already preparing to intern the more prominent refugees despite Kossuth and his associates’ vehement protestations, but matters of political expediency proved stronger. The Ottoman Empire had no interest in war, and neither did the British and French who supported it in the conflict. In the meantime, first the Austrians and then the Russians dropped their demands for extradition. According to an agreement reached between the two sides in January 1850, those unconverted refugees deemed the most dangerous were interned in Kütahya in Anatolia. This group, led by Kossuth, included the former foreign minister, Kázmér Batthyány, Lieutenant General Lázár Mészáros, and Major Generals Mór Perczel and Józef Wysocki. As for the others, some remained in Shumla while others tried to get abroad. The number of those who remained behind at this time was around 730; between them and the converts, at least 250 would remain permanently in the Ottoman Empire.

The internees arrived in Kütahya on April 12, 1850. Kossuth, however, did not remain idle. He was in constant correspondence with those who had emigrated westward, especially Teleki and Pulszky. He also accepted an invitation from Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian democratic politician, and was in contact with the Central European Democratic Committee, which was intended to coordinate the activities of the Italian, German, French, and Polish democratic émigré organizations in London. As a result, he drafted the so-called Kütahya Constitution, which proposed a future governing structure for Hungary. He also issued orders from Kütahya to several persons to organize an underground independence movement in Hungary. Unfortunately, most of the agents were unfit for the task, and the imperial authorities quickly disposed of them and retaliated for these attempts. The lesson was not lost on Kossuth, and he realized all such endeavors were doomed to failure without the support of one of the great powers.

Since the agreement between the powers did not stipulate the duration of Kossuth’s confinement, the Porte lifted the internment when the United States Congress decided to invite Kossuth and his companions and sent a ship to deliver them. In September 1851, Kossuth and his companions were finally able to leave the Ottoman Empire, which had provided them with refuge for more than two years.

The western émigrés

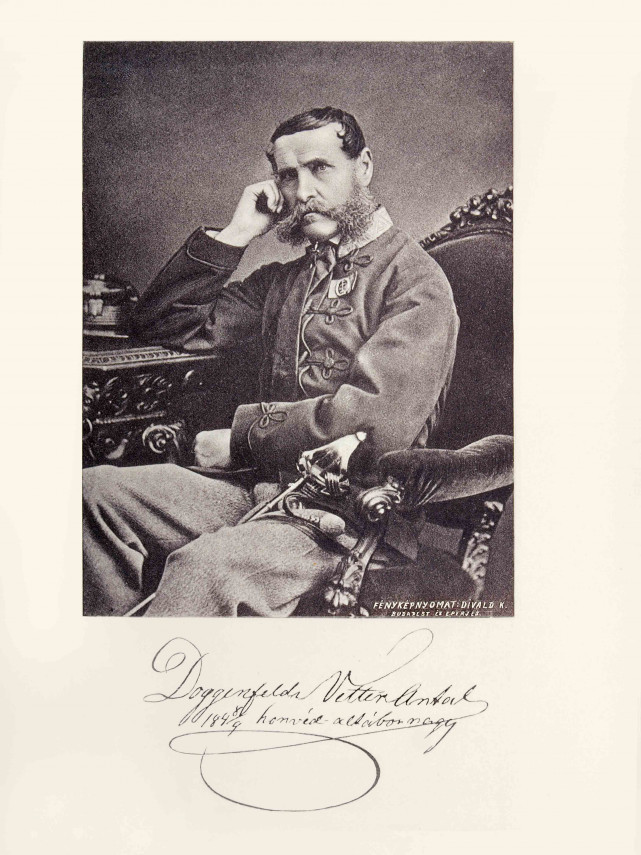

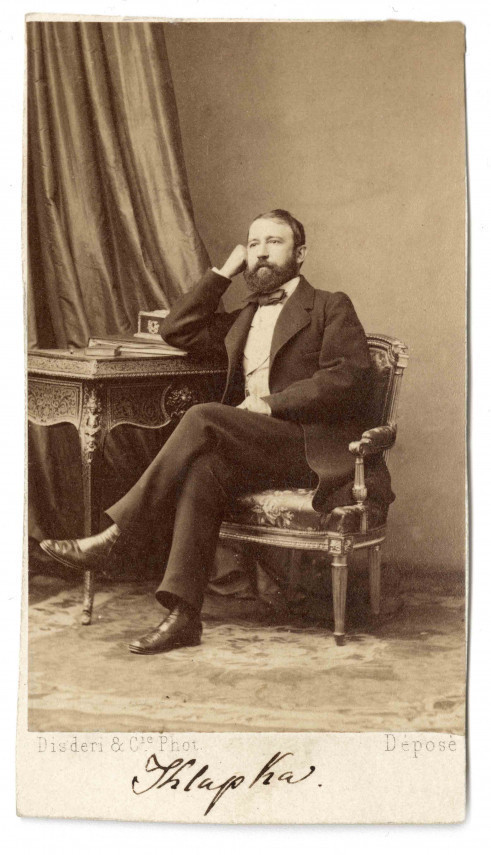

A good number of Hungarian officers chose emigration after the surrender at Komárom, including Major General György Klapka, the commander of the fortress. The fact that they, along with many political figures, were able to secretly escape to the west speaks volumes about the efficiency of the imperial military and police authorities. In late October 1849, the former prime minister, Bertalan Szemere, and parliamentarian Pál Hajnik joined the émigrés in Paris, who managed to obtain blank travel documents while still in Vidin. There is no precise information on the initial number of émigrés who headed west, but it could hardly have exceeded 4-5,000 people.

Kossuth and his entourage leaving Kütahya, September 1, 1851. The departure of the former Hungarian governor-president and other émigrés was made possible by the United States sending a ship to bring them to America for a visit. Lithograph by an unknown master

The western émigrés were mostly concentrated in Paris and London. In 1850, Teleki, Andrássy, and others held talks with Romanian émigrés from Wallachia about the possibilities of future collaboration, but they did not achieve much, because whereas the Hungarians insisted on a unitary Hungarian state, the Romanians were inclined towards some sort of federal solution and considered the status of Transylvania an open question.

In order to ensure coordinated action among the Hungarian émigrés, a central association was established in Paris in January 1851, with László Teleki as chairman and Bertalan Szemere as vice-chairman. When, at a conference in Dresden on December 24, 1850, Austrian representatives tried to promote the idea of Austrian membership in the German Confederation – along with all its provinces (e.g., Hungary and Galicia) – the members of the émigré association sent a lengthy memorandum to the French government, explaining the historical and legal baselessness of such an idea. It is unknown whether the memorandum had any effect on the decision-makers; in any case, the Austrian proposal fell through.

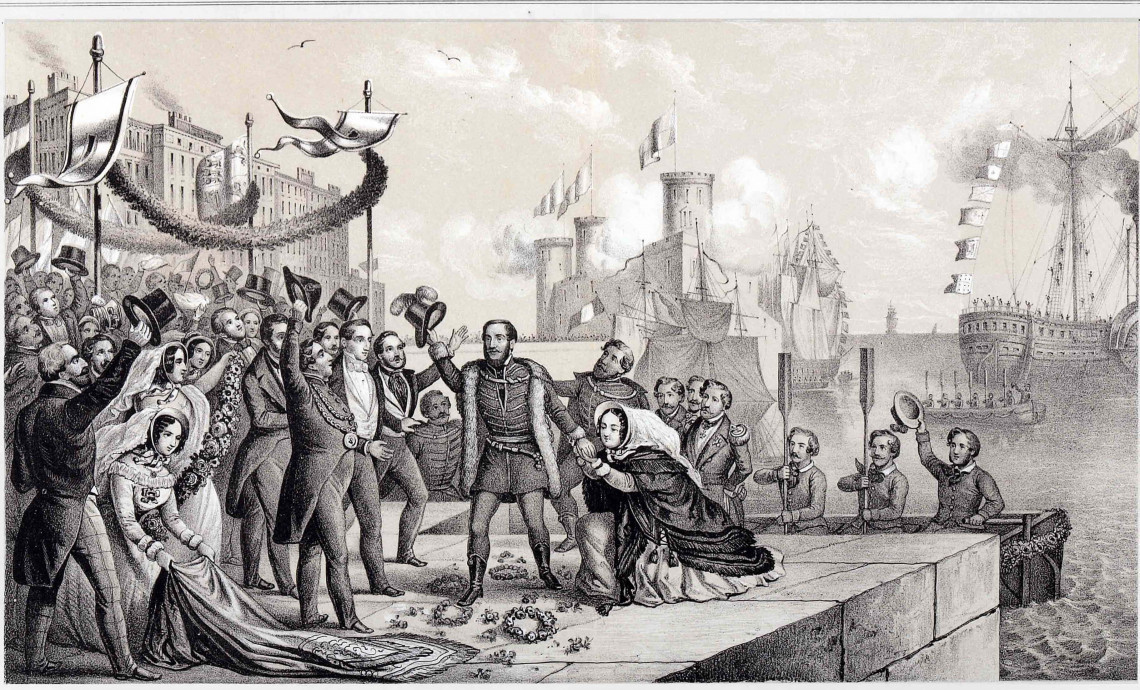

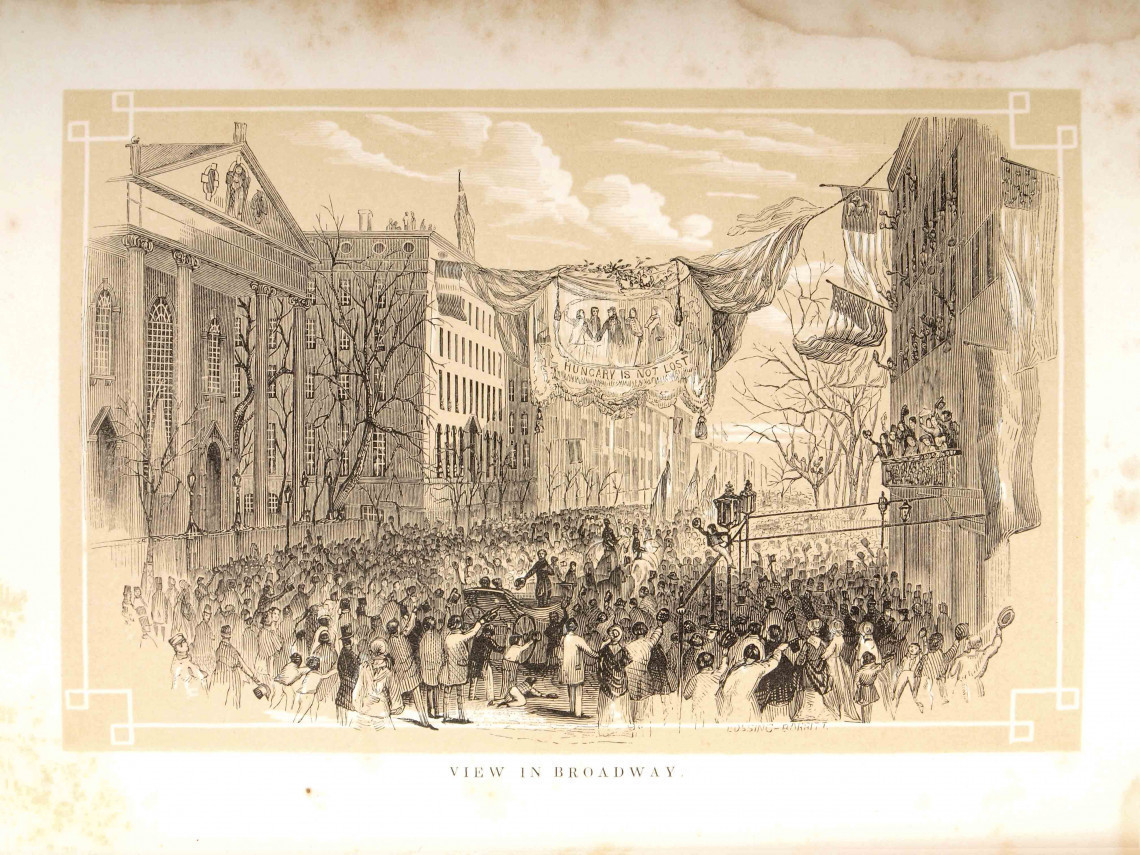

Kossuth arrived in England on October 23, 1851, where he enjoyed almost incredible popularity, speaking at rallies attended by tens of thousands of people. When he arrived in the United States in December, he experienced similar crowds on his speaking tours there. While in America, he was received by President Millard Fillmore, and in January 1852, he attended a ceremonial reception in his honor hosted by both houses of Congress. In both England and America, Kossuth promoted the idea of “intervention for non-intervention,” meaning that if the Hungarian War of Independence were to resume, the United Kingdom and United States should act to prevent Russia from providing Austria armed assistance.

This was a thoroughly naïve idea, as British policy perceived the Austrian Empire as a guarantor of the European balance of power, while in America it had to contend with a strong tradition of isolationism since the time of Washington. Moreover, Kossuth’s position was seen through the increasingly acute prism of the North-South conflict within the United States, with the South viewing the serf-emancipator Kossuth as a secret abolitionist while the North was disappointed to note Kossuth’s unwillingness to condemn slavery. Thus, although the English and American visits benefited the popularity of both the Hungarian cause and that of Kossuth personally, they had a negligible effect on the fate of the defeated Hungary.

Hungarian refugees had already made their way to the United States before Kossuth’s visit, with several hundred settling in the country. Around 100 of them fought for longer or shorter periods in the Civil War, mostly on the Northern side, between 1861 and 1865. Seven of them eventually reached the rank of general: Sándor Asbóth as a brigadier general, Gyula Stáhel-Számwald as a major general, and Frigyes Knefler, Jenő Kozlay, Károly Mándy, György Pomucz, and Albin Schoepf as brevet brigadier generals.

Unrealized hopes

Dissolution among the western émigrés began as early as 1850, with many returning home after the first domestic amnesties were announced. The increasingly escalating Russian-Turkish conflict held out the hope of restarting the War of Independence. Starting in the spring of 1853, the Hungarian émigrés hoped that Austria would join the Russo-Turkish War on Russia’s side, thus allowing the conflict to spread to the Austrian Empire.

The war broke out in October 1853 when the Turks attacked; General György Klapka left for Istanbul that same month. Despite hopes of obtaining the position of commander-in-chief of the European troops in the Turkish Army, he was forced to leave the Ottoman capital in August 1854 without success. Although the Turks were pleased to have Hungarian émigrés with military experience serve on their side, they had no intention of elevating any of them to a position that could provoke Austria, which had maintained a neutral position for the time being. Dozens of Hungarian émigrés took part in the war, with Richard Guyon, György Kmety, József Kohlmann, and Miksa Stein serving in the Ottoman Army with the rank of general; despite this, the war failed to bring any benefit to the Hungarian cause.

In the years following the Crimean War, Hungarian émigré life exhibited a certain ebb and flow. Failure did not calm but instead exacerbated the antagonisms between Kossuth and the others. Kossuth himself made his living from the mid-1850s onwards mostly by writing newspaper articles and giving lectures.

The late 1850s, however, saw a new opportunity present itself. The French emperor, Napoleon III, had allied himself with the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in order to gain two Italian territories – Savoy and Nice – from the Austrian Empire in what would become the Second Italian War of Independence. Kossuth was also involved in the anti-Austrian negotiations. Moreover, Kossuth, László Teleki, and György Klapka also formed an “émigré government” – the Hungarian National Directorate. They hoped that Napoleon III would restore Hungary’s independence following Austria’s defeat.

Kossuth made it clear to the French emperor that he would only summon the Hungarian people to arms if French armies were to appear on Hungarian soil, if the emperor were to declare the restoration of an independent Hungary as a war aim, and if the cooperation of the Romanians, Serbs, and Croats were guaranteed. The caution was warranted since, despite the allied Franco-Piedmontese army defeating the Imperial Austrian Army at the Battle of Solferino, Napoleon soon concluded first an armistice and then peace with Austria. The war itself saw the formation of a 3,200-strong Hungarian legion on the Italian side, mostly composed of former prisoners-of-war, but with the swift conclusion of peace, it was no longer deployed.

Hungarians were present when Garibaldi launched his expedition in May 1860 aimed at liberating the Dual Kingdom of Naples and Sicily. First Lieutenant Lajos Tüköry was mortally wounded during the capture of Palermo, while Colonel István Türr played an integral role in one of the most decisive battles of the campaign, at Volturno. Garibaldi honored Hungarian participation in the expedition by establishing the Hungarian Legion in Palermo in July 1860, with a staff of 91. Unlike other foreign volunteer units, the Hungarian Legion became part of the army of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, with 2,337 men having served in its ranks for various terms until 1867. Kossuth and his associates had hoped the legion could form the nucleus of a new Hungarian army; however, since another Italo-Austrian war did not occur until 1866, the unit was deployed in southern Italy against armed royalist units, the so-called brigantaggio.

Kossuth’s triumphal procession on New York’s Broadway, on December 6, 1851. The former Hungarian leader left Southampton for America on November 20, 1851, to thank the American people for the help in obtaining his freedom. The Americans received Kossuth with respect almost befitting a sitting head of state. The banner in the picture reads “Hungary is not lost” and is a paraphrase of the opening line of the Polish national anthem Mazurek Dąbrowskiego, which states “Poland is not lost.” Lithograph by an unknown artist

Kossuth and his colleagues hoped that the Austrian Empire would eventually invade northern Italy in order to regain its lost Lombardy territories, an act that would enhance the standing of the Hungarian émigrés. To this end, they tried to establish closer ties with the Italian government of Camillo Cavour, which was quite generous in supporting the aspirations of the Hungarians. Nevertheless, a renewed war did not break out in Italy in 1860, while in Hungary itself the Austrian king had undertaken steps to consolidate his rule.

With the Kingdom of Italy preoccupied with incorporating its newly acquired territories in central and southern Italy, the Italian governments that assumed office after Cavour’s death became more reticent in their support for the Hungarian émigrés. Then came another blow – László Teleki, who was in Dresden on a private matter, was arrested by the Saxon authorities and extradited to Austria. Granted a pardon by Emperor Franz Joseph, he nevertheless resumed political activities as head of the Resolution Party (Határozati Párt) in the Hungarian National Assembly in 1861. Realizing that the majority of his party colleagues did not support the 1849 program, he shot himself in the head on May 9. The monarch, for whom even the position of 1848 represented by Ferenc Deák, head of the Address Party (Felirati Párt), was also unacceptable, soon dissolved parliament.

Kossuth’s plans

A fundamental precondition for launching a new war of independence would have been reaching a consensus with Hungary’s national minorities and its neighboring states. Kossuth and Klapka pursued several steps in this direction, and Klapka and his envoys undertook repeated discussions with Alexander Cuza, the Romanian prince of Moldavia and Wallachia, about the Hungarians being able to use the two principalities as a staging area for an attack on Transylvania.

In 1862, Kossuth and Klapka conceived the plan of an alliance of peoples living along the Danube – the Danube Confederation. The confederation, which affirmed Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia, Romania, and Serbia as equal partners, would have ensured the complete internal independence of the participating states while protecting each against external attacks as a single strong power. However, the draft intended as a basis for negotiations was published in the Milanese-based L’Alleanza, and the idea was met with serious criticism both in Hungary and the other states concerned.

Meanwhile, Kossuth’s own influence within Hungary was on the decline, and his relations with the domestic opposition were practically non-existent. From the autumn of 1861, the former parliamentarian György Komáromy, who had previously been regarded as Kossuth’s confidant, and Count Tivadar Csáky, who belonged to the newer generation of politicians, preferred to maintain contact with Klapka. Even Teleki’s former party – the Resolution Party – ceased to be a reliable source of information for Kossuth. Kossuth himself had grown aware of this, and thus in May 1863, he began creating another secret domestic resistance organization – the National Independence Committee. The participants, however, were eventually betrayed to the Austrian secret police by the former army colonel Lajos Asbóth – a police informant since 1862. When the Austrian secret police launched a crackdown in mid-March 1864, they were able to round up not only the actual participants of the underground organizations but also a number of politicians who were only loosely connected to them.

New hopes would emerge in late 1865, however. The Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck believed the time had come to end the Austro-Prussian rivalry for leadership of a unified German state, and he decided to settle the conflict by force of arms. To this end, he obtained the support of Italy, which had its own conflict with Austria over Veneto. The Prussian-Italian alliance’s war against Austria seemed to be a good opportunity for realizing Hungarian independence plans.

The end of daydreams

The plans woven by the Hungarian emigrants were grand and novel but did not enjoy the support or inclinations of any of the great powers, as was the case in 1859. The Italian government was willing to provide only one-tenth of the money promised by the king for military campaigning in the east. It soon became clear that the Italians could not be relied on in any case, as the Italian Army had suffered a catastrophic defeat in the first week of the war, on June 24. Moreover, hopes of the Italian fleet making a landing in Dalmatia were dashed by its defeat at Lisa on July 20.

Although the Prussian Army succeeded in destroying the Austrians at Königgrätz on July 3, Bismarck had no intention of dismantling the Habsburg Empire; he only wanted to remove it as a factor in a unified Germany. In mid-July, Klapka embarked upon organizing a Hungarian Legion in Prussia comprised mostly of former Hungarian prisoners of war. On August 3, the roughly 1,200-strong force entered Hungarian territory through the Jablonka Pass in the Western Beskids. Although the campaign had been covertly supported by the Prussian government, it subsequently forbade it, leaving Klapka with little else to do but to return to the Saxon territories under Prussian occupation, leaving his work unfinished.

The resulting peace treaties ending the war saw the Italians receive the province of Venice, thus ceasing all common ground between the Hungarian émigrés and the Kingdom of Italy vis-à-vis Austria. Thus, events became a repeat of 1859. The great power only contacted Kossuth and the émigrés to use them as a lever to force Austria to make peace as soon as possible.

The year 1866 marked the last opportunity for the Hungarian émigrés to restart the Hungarian War of Independence with the assistance of some external power. Going forward, the Italians lacked the strength and the Prussians the will. By this time, most of the émigrés had become fatigued by the constant dashing of their hopes year after year, and so they returned home after the 1867 Compromise and integrated themselves into the new order. It is symbolic of the changing times that 1867 also saw Franz Joseph I appoint Count Gyula Andrássy as the first prime minister of the now dual kingdom, considering Andrássy had been sentenced to death in absentia in 1851, and during his symbolic hanging had had his name nailed to gallows alongside Kossuth’s.

One of the few exceptions to this conciliatory trend was Kossuth himself, who regarded the Compromise as fatal for Hungary and wrote articles in the newspaper Negyvenkilencz, in Italy, trying to dissuade the Hungarian public from supporting the deal. However, those making the decisions were no longer listening to him.

***

Was the path taken by the Hungarian émigrés one of failure? If viewed from the perspective of their ultimate intentions, it undoubtedly was. Although they tried to exploit every major international conflict over the course of 19 years as a means of restoring Hungarian independence, none of the European powers had a long-term interest in seeing the Habsburg Empire dismantled. Nevertheless, the mere existence of the émigrés and their propaganda activities in the years 1849 to 1867 kept the Hungarian cause alive in international discourse and helped establish a lasting positive image of Hungarians and Hungary in Western public opinion. At the same time, the mere existence of the émigrés posed a constant threat to the Habsburg Empire and was thus one of the factors compelling Franz Joseph and the imperial government to effect a compromise with the Hungarians.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)