Following the Ottoman victory over the Hungarian army at the battle of Mohács in 1526, a struggle ensued between two kings claiming the Hungarian throne – János Szapolyai, the voivode of Transylvania and vassal of the Turkish sultan, and Ferdinand Habsburg, the archduke of Austria. It was a struggle that would continue for over a decade. Neither was able to oust the other from power, although each used every means at his disposal. Both tried to increase their standing within the country by means of threats, promises, and donations while waging relentless diplomatic warfare against each other in the royal courts of Europe and at the Holy See. The leaders of the Hungarian estates of the realm sided first with one king and then the other, which only increased the chaos and disunity of the country. The two kings finally cut the Gordian knot with an agreement whose immense consequences were surmised by many of their contemporaries: they divided the Kingdom of Hungary between themselves by rendering permanent their respective spheres of control that existed at that time. The road that led to this forced settlement known as the Treaty of Várad was a long one and was fraught with difficulties.

Starting in 1530, the struggle between János and Ferdinand had entered a new phase. Both kings sought to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the other and drive their rival out of the Kingdom of Hungary while simultaneously proclaiming their quest for peace and reconciliation at home and abroad. The Polish king, Sigismund I the Old, was the main supporter of European recognition of János’s claim to Hungarian kingship. Starting in 1527, Sigismund’s diplomats began organizing and conducting numerous meetings and truce negotiations between the two Hungarian kings. By the end of 1530, both kings, it seems, realized that they would be unable to permanently oust their opponent from power on their own. Hungary, meanwhile, was drifting inexorably towards de facto territorial division.

A lack of trust

Negotiations between the two Hungarian kings began in the Polish city of Poznań in October 1530, thanks to the mediation of the Polish court, but broke down a month later amidst mutual distrust. Sigismund I advocated peaceful reconciliation between Christian parties instead of war, and in his letters he sought to promote the maintenance of the Respublica Christiana, that is, Christian unity and cooperation. Sigismund asked King János to cast aside hatred and enmity in order to foster tranquillity in the Christian world and to put forward acceptable terms for Ferdinand because all of Europe favored peace and concord between the two of them. Although the negotiations in Poznań ended in failure, János and Ferdinand were able to conclude a truce at Visegrád in early 1531, first for three months and then for a year.

Pope Clement VII also tried to resolve the tense situation between the two Hungarian kings, urging first one and then the other to reach an agreement. In 1530, during an exchange of ideas with Ferdinand’s envoy, Andrea Dal Borgo, the pope suggested that Ferdinand should endeavor to make peace with János. If János insisted on the royal title, then Ferdinand should renounce some of the provinces subject to the Hungarian crown, which János would then rule. In this way the costs of defending the country would be divided between the two of them.

View of Várad, 1644 (Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolffenbüttel)

During these months, King János also tried to convince the Holy See of his goodwill, sending several letters to the pope and making it known on numerous occasions, through his envoys, that he was ready to reach an agreement with Ferdinand in the interests of Christianity. In February 1532, when addressing Pope Clement VII in Rome, János’s envoy, Antal Verancsics, emphasized his lord’s faithful adherence to the Christian religion and the Holy See, adding that János had been forced to make an alliance with the sultan solely out of necessity and that he was sincere in wanting to make peace with Ferdinand.

Stalled negotiations

Truce negotiations carried on through 1532 and 1533 but did not yield any results, although King János expressed his willingness to seek peace and reconciliation when corresponding with Ferdinand. János’s chief diplomats in negotiating with Ferdinand’s Habsburgs were the learned humanist István Brodarics (c. 1471–1538) and his companion, the Franciscan monk Ferenc Frangepán (1490?–1543).

A 1532 letter by Brodarics, who had excellent Polish connections, addressed to the Polish vice-chancellor, Piotr Tomicki, sheds some light on the initial difficulties of the negotiations. Broderics lamented the failure of the peace negotiations, with he and his associates viewing the Habsburgs as unwilling to compromise even though the sultan had already given his approval. In another letter, Brodarics expressed regret that this would lead to another armed conflict that would involve the spilling of much Christian blood. He mentioned that when King Sigismund of Poland persuaded János to send envoys to Charles V, Ferdinand’s brother and the reigning Holy Roman Emperor, and was prepared to send his envoys to the farthest corners of Germany, his opponents would no longer receive them.

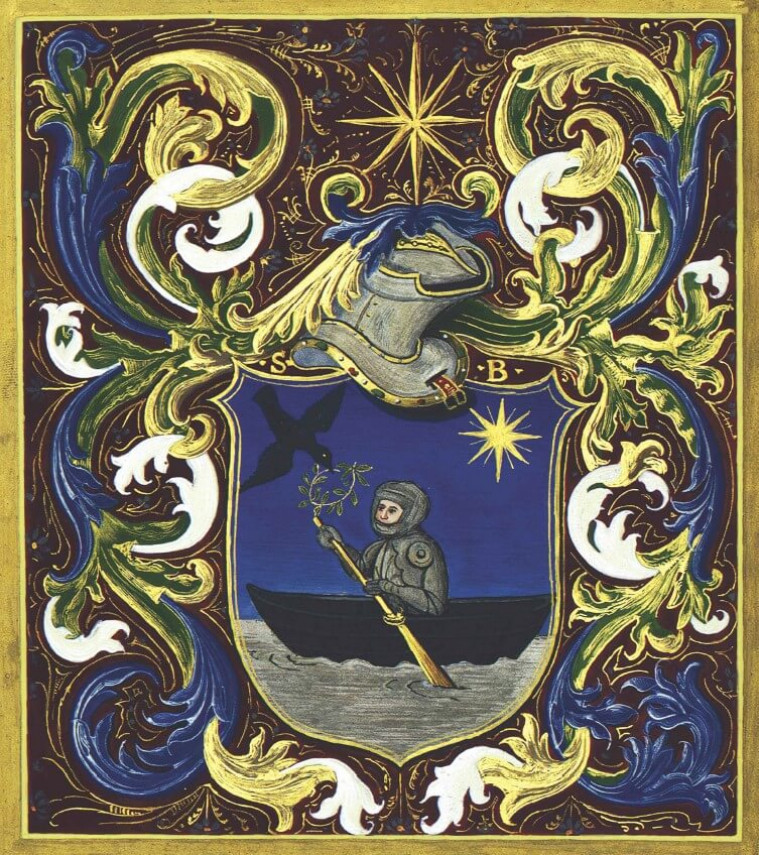

Reconstruction of István Brodarics’s coat of arms, 1517

In 1533, Brodarics asked Tamás Nádasdy, an influential Hungarian nobleman, to assist him in bringing about peace. However, he also noted that the peace would have to be one that the sultan would accept; otherwise, both they and their opponents would be destroyed. It would seem that by 1533, the leading political figures already seemed to have sensed, although they were loath to admit it, that the kingdom would have to be permanently divided between the two kings. This danger was also apparent to Ferdinand’s Hungarian advisors, and they, like the leading political figures of the day on both sides – even the Habsburg court envoy to Prussia, Cornelius Schepper – believed that if Hungary was divided, it would be destroyed. The Hungarian advisors wrote in their memorandum to Ferdinand: “Hungary has no future without a sole king.”

When a delegation led by Brodarics left for Vienna in September 1534, Ferenc Frangepán, archbishop of Kalocsa, and István Werbőczy, a Hungarian legal theorist and statesman, went with them. Their stated aim was to secure a peace with Ferdinand regardless of the cost. King János’s chief envoy then contacted the most influential man in Ferdinand’s circle, Elek Thurzó (1490–1543), chief justice of the Kingdom of Hungary, but refused to negotiate anything with Thurzó until Ferdinand handed over the entire country to János. Since this did not happen, they did not get any further than some preliminary talks. In October 1534, Ferdinand wrote about the negotiations in a letter to his elder brother, Charles V, expressing that although the Hungarians were not at all in favor of their country being dismembered, Janos’s supporters would still be willing to effect a compromise with him if he promised to help the country against the Ottomans.

In his history of the conflict between János and Ferdinand, the Slavonian nobleman and later secretary to Elek Thurzó, János Zermegh, noted that during these negotiations, which continued with varying breaks into the following spring and summer, the envoys made profuse speeches before Ferdinand about the need for an agreement.

In February 1535, Brodarics wrote to Piotr Tomicki that the peace negotiations in which he was taking part had been suspended. “If our kings,” wrote Brodarics, “because both of them lay claim to the country, were wise, they would come to an agreement; if not, God alone knows what will happen to us and ultimately to all the countries around us.”

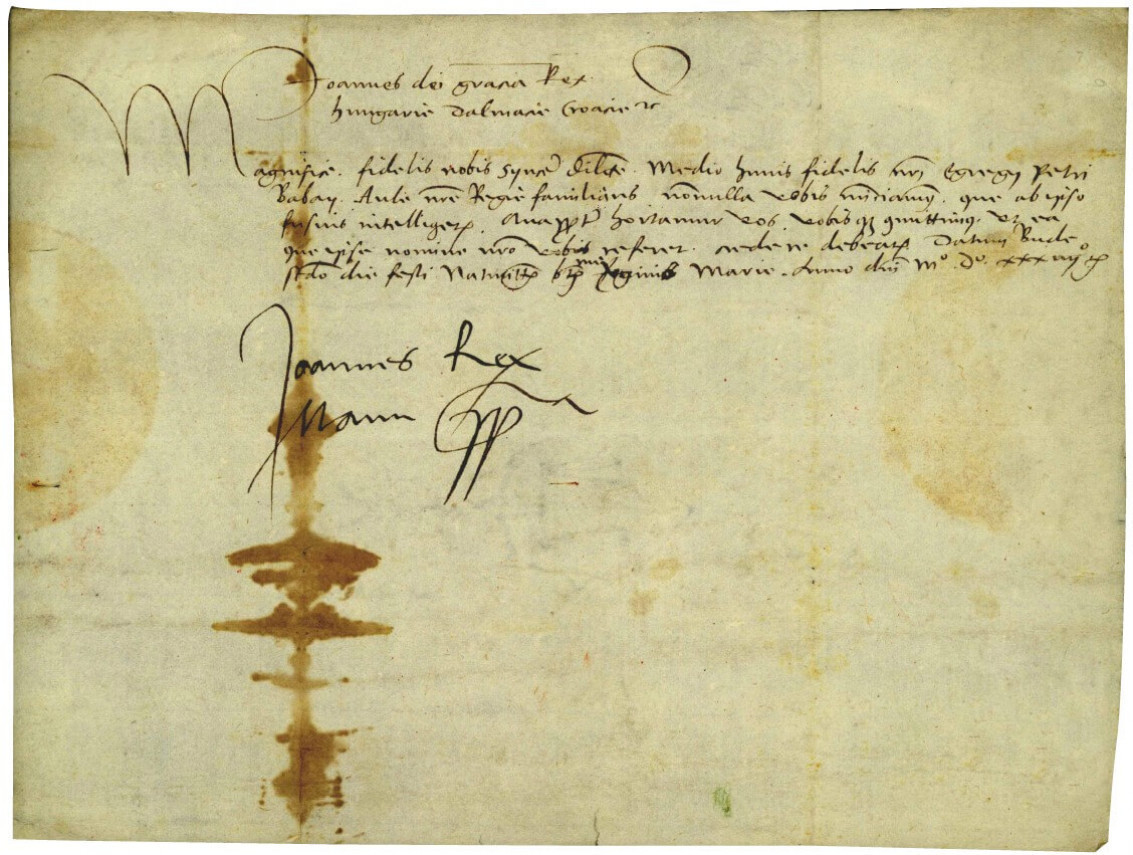

King János’s handwritten signature on a letter to Tamás Nádasdy, 1534

A truce is declared

On August 21, 1535, negotiations in Vienna resulted in a truce that suspended the fighting until March of the following year. A copy of a speech made by Brodarics on March 17, 1535, during the negotiations, has fortunately remained intact to this day. More than anything, Brodarics argued for the need to make peace, and, recounting the reasons for his arrival, he spoke eloquently about how much loss and destruction had been inflicted on Hungary, Austria, Slavonia, and Transylvania, and the towns and cities, including Buda, due to the renewed warfare, and about how many of his Christian brothers and sisters had been killed or taken into captivity by the enemy.

Brodarics reminded Ferdinand of the Latin proverb that when two parties are in a dispute, a third always rejoices. He pointed out that peace was being hindered by those who were saying nothing should be left to King János because whatever would be left to him would fall into the hands of the Turks. Countering this, Brodarics argued that not a single castle, town, or part of the country had been lost to his lord, apart from the territory remaining in the hands of the Turks following the Battle of Mohács (Brodarics was referring here to the Syrmia region of southern Hungary). Nevertheless, his king was endeavoring to reclaim everything he could from the Turks.

Brodarics then went on to list the beneficial consequences that could accrue from an agreement with János: Ferdinand’s authority and prestige would increase, the glory, splendor, and power of his name would be enhanced without measure, and everyone would praise him so highly that the greatness of his name would endure for posterity. And the populace, exhausted and impoverished by so much destruction, would finally breathe a sigh of relief, and thus many would be disposed in his favor. “And we, wretched and unhappy Hungarians,” he wrote, “especially those exposed to great daily dangers lurking about our borders and who are awaiting suffering, will be freed from those many misfortunes and will be summoned back from death to life.”

The great seal of Ferdinand Habsburg, 1542

Brodarics raised the possibility of an extensive anti-Turkish alliance before Ferdinand: Austria, Germany, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Lusatia, Poland, and – naturally – Hungary especially, together with Slavonia, Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia, could merge into one body, submitting themselves to a single ruler. Here he was implicitly referring to Ferdinand as the only possible ruler this could be. With God’s help, Brodarics explained, this opportunity must be seized and peace made on fair terms, as it would benefit all nations, and for this reason the prince he represented (King János) was ready to do all in good faith.

Paul III (r. 1534–1549), who assumed the papacy in October 1534, took a keen interest in the events in Hungary and sent envoys to both kings. However, the Viennese court took offense that the new pope had sent the prestigious envoy Girolamo Rorario (Hieronymus Rorarius) to János because they believed that in doing so, the Holy See had thereby rendered the voivode arrogant and conceited – as mentioned by the papal nuncio to Ferdinand I, Pietro Paolo Vergerio, in one of his letters.

Efforts by the estates of the realm

In the first half of the 1530s, Hungary’s leading political figures also sought a solution to the conflict between their two kings. The first so-called kingless diet – a gathering of the estates of the realm – was provoked by the Visegrád truce agreement concluded in January 1531 (mentioned above), about which the estates had not been informed beforehand and which caused great alarm and outrage throughout the country once it became known. This agreement was the first that foresaw the alarming prospect of the country being divided, and it is perhaps not an exaggeration to say that such a division, albeit provisionally, had already taken place, for the agreement stipulated that both kings would rule, command, and collect taxes in the territory they held.

Pál Várday, the archbishop of Esztergom, was the first to propose that the nobles supporting János should hold joint meetings with Ferdinand’s followers, which was followed by a similar proposal by Péter Perényi, Ferdinand’s voivode of Transylvania, in 1530. In March 1531, representatives of the Hungarian, Slavonian, and Croatian estates met for the first time in Bélavár, Somogy, in southern Hungary. At a gathering numbering about a hundred people, Péter Perényi argued that they should side with King János and recognize him, and through him the sultan as their “merciful lord,” because the Turkish ruler would then spare the country from further destruction. No decision was made at that time, but the nobility continued their discussions in Veszprém in May that same year, but since both kings forbade their supporters from participating, the attempt was rendered stillborn.

A diet of the estates eventually took place in Zákány in 1531, at which those present agreed to reconvene in Kenese, near Lake Balaton, in early 1532. Organization of the latter gathering was entrusted to Bálint Török on behalf of Ferdinand’s supporters and to Tamás Nádasdy on behalf of János’s. The leading figures from both parties nevertheless believed that the country should be united under the scepter of a single ruler in order to avoid its destruction, namely, that ruler capable of defending the country from the Ottomans quickly and effectively. Nádasdy made a lively case in favor of János, arguing that Ferdinand lacked the material power to recapture the lost frontier castles but that King János could achieve this peacefully and that after the king’s death no Turkish dignitary would ascend to the throne, but only a Christian.

The diet in Kenese took place in January 1532. The leading figures among Ferdinand’s supporters were Tamás Szalaházy, the bishop of Eger, and Elek Thurzó, as well as members of the king’s council – Sigismund von Herberstein, the Bohemian royal courtier Adalbert von Pernstein, and Jan Kunowitz, president of the Moravian chamber, whose task it was to convince those present to support Ferdinand’s candidacy through promises of positions, donations, and other benefits.

Ferdinand thence ordered his supporters to Pozsony (Bratislava). Few high-ranking nobles made an appearance; nevertheless, the Pozsony gathering was still large, with many common nobles represented. Although King János forbade his followers from participating, several were present nonetheless. The tension regarding the situation is well-illustrated by a secret report that informed Ferdinand that the Hungarians, if unable to choose between their kings, planned to establish a republic and establish relations either with the German imperial authorities or the Turks.

Charles V’s envoy, Count Wolfgang Montfort-Rothenfels, and the papal envoy, Archbishop Vincenzo Pimpinella of Rossano, in their letters to the Hungarian estates, announced the certain and expected assistance of the Christian nations but did not mention any specifics; nevertheless, they asked them not to abandon the two claimants and not to make any hasty decisions. Hieronymus Łaski – a supporter of King János, however, urged the nobles to do just the opposite in his own letter. He informed them that Ferdinand had no supporters in the Holy Roman Empire and that his imperial brother would not help him either, as he was preoccupied with a renewed war with the French; thus, they could not count on imperial help but should all pledge loyalty to King János.

The great seal of János Szapolyai, 1532

In the end, despite the heated debates, the question of an alliance with the Turks or the Germans remained unresolved, and discussion of the country’s affairs was postponed to a subsequent diet, this time in Berhida, near Lake Balaton. Ferdinand did everything in his power to prevent the diet, which had been announced for March 12, 1532, from taking place. In his letter to the nobles, he asserted that he was entitled to the Kingdom of Hungary both by divine right and by human law, and the only reason for his absence from the country was that he was trying to obtain help from the imperial princes. János’s supporters rejected this, and no resolution was found here either. Tamás Szalaházy and Elek Thurzó, appointed governors by Ferdinand in 1531, were uniformly opposed to these kingless diets, since Szalaházy believed that they were the contrivance of the sultan’s grand vizier, Ibrahim Pasha, who wanted to help a third person – perhaps Peter Perényi – to the royal throne by deposing the two claimants.

Portrait of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, 1531

The kingless diets, in which nobles from the competing parties sought an agreement among themselves in choosing a ruler with the unquestioned ability of driving the Turks out of the country, were doomed to failure. On the one hand, the opposing claimants used these diets to wage political campaigns against each other and recruit new converts. On the other hand, the high-ranking nobles and ecclesiastics were unable to reach a unified position on how to save the country, although separate agreements were regularly made between various groups of nobles and the kings. Meanwhile, there were yet others, by no means a small number, who, angling among the competing parties and siding with first one king and then the other, found excellent opportunities for increasing their wealth. Although it may have been an acceptable justification for asserting self-interest that the landowners who were defending their private estates were also defending the country as a whole, there is no basis for asserting that such personal political intrigues indicated a conscious or perhaps coordinated class politics.

Charles V gets involved

During discussions in Vienna in October 1535, János’s envoys put forward a new position – their king no longer wished to negotiate with Ferdinand but with his brother and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In the basic document drawn up for discussions with the emperor, certain elements of the later Várad agreement can already be recognized: János offered to renounce the entire country, including Transylvania, but would continue using the title of king for the rest of his life; moreover, he would cede Buda and Temesvár (Timișoara) to the emperor, which would only accede to Ferdinand after his (János’s) death or following the recapture of Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade).

In exchange for all this, János first requested the return of the Szapolyai estates, along with other valuable estates, that had been occupied by the Habsburgs, which, in addition to assuming the title of prince of Szepes (Spiš), could provide him and his successors with the appropriate rank and financial circumstances. He also requested that 17 counties of the country remain in his possession, in addition to the towns of Szepes region and some mining towns, monetary compensation, and a Habsburg wife. János’s envoys brought these proposals to the emperor in Naples in January 1536 via Rome, where they had been prevented from appearing before the pope by the emperor’s diplomat, Archbishop Johannes von Weeze of Lund.

Portrait of Ferdinand I as king of Hungary, 1531

Although Charles V did not object to the points presented to him, Weeze was very hostile to the proposals and tried to minimize the monetary compensation imposed on Ferdinand in the planned agreement while maximizing the amount of Hungarian territory he would receive in the proposed settlement. The Naples mission was ultimately unsuccessful, with the main reason being that the negotiating parties could not agree on ownership of the larger manor holdings and the Szapolyai family estates. Negotiations continued over the following months, but there was still no prospect of an agreement, as neither claimant wished to surrender any of the territories they ruled. King János mainly insisted on retaining Transylvania and Kassa (Košice), while Ferdinand had no wish to recognize János’s kingship, preferring him to be content with the title of viceroy or palatine, or its Hungarian equivalent – nádor. Brodarics, meanwhile, journeyed tirelessly, but with increasing hopelessness, between Buda and Vienna.

By 1536, the issue of an agreement between the two kings was increasingly on the agenda of the diet of the Hungarian estates. The internal war had been going on for almost ten years now, and quelling it had become the main goal of the political elite, as both sides felt that a third party would emerge triumphant in the contest between János and Ferdinand. The threat of Ottoman raids and campaigns year after year kept the population in constant fear. At the diet held in Várad in 1536 and presided over by János, the estates were pleased to hear that János had initiated peace talks; nevertheless, they believed peace could only be achieved if the supporters of the two kings were to reach a consensus.

Brodarics, who played an influential role on the Szapolyai side, informs us that János, while constantly expressing his desire for peace, was as reluctant to agree to terms as Ferdinand. At times, he became offended and stopped attending meetings for a number of reasons. Perhaps the most blatant of these, going beyond simple self-interest, was that the Habsburg party – not recognizing János’s legitimate claim to kingship – usually referred to him as voivode. János, however, was no more correct in his conduct, for while negotiations continued, he seized Kassa in December 1536 and, armed to the teeth, was ready to seize further territories in Upper Hungary. Details surrounding the negotiations can also be found in the letters of the archbishop of Lund, who was already in Várad in the summer of 1536, representing Ferdinand and Charles V. His records reveal that János dragged out the negotiations for several reasons, most notably waiting for the outcome of Charles V’s war with the French while secretly trying to lure as many pro-Ferdinand nobles as possible to his side.

The role of Friar György

In 1536, King János’s chief advisor, Brother György Martinuzzi, headed the negotiating delegation, while Johannes von Weeze served the same role on the Habsburg side. Brother György’s presence was justified by the fact that the Habsburg brothers regarded the acquisition of the Kingdom of Hungary to be their common cause, even if Charles had failed his younger brother on more than one occasion in the latter’s contest with János.

The negotiations continued despite great difficulties. However, pressure on the part of the Hungarian estates to conclude a peace agreement must have been quite strong. This is shown by the fact that Weeze once wrote to Charles V in the summer of 1536 that if peace were not achieved, even the life of Friar György could be in danger. In Weeze’s opinion, Friar György seemed erratic and inscrutable, was secretive, and was always coming up with new proposals, thus hampering negotiations. The other leaders of János’s party – Chancellor István Werbőczy and Archbishop Ferenc Frangepán of Kalocsa – also believed there would be no peace if Friar György were opposed to the terms and that he was obstructing the negotiations at every turn.

Imprint of Friar György’s ring seal: The lower part of the shield depicts a unicorn prancing to the right – this element of the coat of arms was likely taken from the Szapolyai family coat of arms – while the upper part shows a raven taken from the coat of arms of the Pauline Order, which is holding a crust of bread in its beak, perhaps preparing to feed the unicorn.

When Weeze questioned King János – or, as he called him, the voivode – about peace, János replied that he wanted peace with the same determination as before, but he saw that the Emperor Charles V was busy with his war with the French and could not help Hungary. His reluctance was also occasioned by the fact that he had known since the early 1530s that he would have to – or should have to – obtain the sultan’s approval for his negotiations and thus had to consult with the Porte from time to time. Nevertheless, negotiations took place in secret in 1536–1537, without the sultan’s knowledge.

Szapolyai’s supporters also stalled for time in order to squeeze as many concessions from Ferdinand as possible, so much so that Weeze, losing hope for an agreement, wanted to head home. From the archbishop of Lund’s letters, we know that during the final stages of the negotiations, discussions were already taking place at two levels: secret meetings were attended by Weeze and Friar György, whom he called all-knowing, and Ferenc Frangepán, while public discussions were held in the presence of János Statileo and other advisors.

Weeze’s diary-like notes recount a private conversation he had with Friar György on November 30, 1537. The negotiating parties met in Rozgony (Rozhanovce), near Kassa, where Péter Perényi and General Leonhard von Vels were also present. Brother György assured the archbishop that he would do everything in his power to effect an agreement. Then, assuming a more confidential tone, he continued:

“I would ask that after the conclusion of the peace that I be honoured by his imperial and Roman majesties, for although I am a monk, I am still a man. I cannot request a bishopric, money, or goods from their majesties but would be content with whatever their graces grant me if they deem me worthy of it. For there is no one else in this whole country who knows the nature of the Turks, the Serbs, the Vlachs, the Moldavians, and the Hungarians as I do and how to deal with them. There are people in this country who claim they know everything, but they don’t know how things actually are. Their actions are driven by greed, the desire to be rich and to live in luxury.”

In the furtherance of peace, Friar György asked Weeze to support him before the two Habsburg monarchs, and Weeze agreed to do so. The friar then added that if any uncertainties were to remain after peace was concluded, they should be addressed to him alone, for he would help them find a solution.

Peace is not an alliance

Negotiations between the two kings were hampered by mutual distrust. As a result, peace could not and did not lead to an alliance, much less a coalition to defend the Respublica Christiana against the common enemy, despite the efforts of papal diplomacy to restore the interests of Christianity to the memory of both kings. Moreover, there could be no talk of an anti-Turkish alliance on János’s part, as he had been a pro forma ally of the sultan since 1528, although in reality his subject.

The complexity of the situation was made manifest in a letter written by the Viennese nuncio, Bishop Giovanni Morone of Modena, in September 1537. His Holiness should not presume – the bishop wrote, conveying Ferdinand’s position to the papal secretary – that an agreement with János would signify an alliance against the Turks. If the “voivode” had wanted to ally with Ferdinand against the non-believers, peace would already have been achieved, since this was Ferdinand’s fundamental condition for an agreement, and if they had agreed on this point, they would have found it easier to reach agreement on all the others. However, in the absence of an anti-Turkish alliance, making peace would be very dangerous for all of Christendom. Ferdinand believed that if the voivode were to remain a friend of the Turks, Hungary would be exposed to continuous incursions by Turkish armies. Although there were elements of truth in this argument, Ferdinand was obfuscating the issue and placing all the obstacles to a settlement before the Holy See on János. In reality, Ferdinand’s primary goal was nothing less than acquiring the entirety of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The Treaty of Várad, which theoretically ended the hostilities between the two kings, was concluded on February 24, 1538. János and Ferdinand mutually recognized each other as kings of Hungary and divided the country’s territory between them according to the status quo. Importantly, János also agreed that after his death Ferdinand would inherit his part of the kingdom, even if János were to have a son.

Regarding the right of succession to the throne, the treaty stipulated the right of succession belonged to the House of Habsburg in the event of János’s death and further stipulated that after Ferdinand’s death, his lineal descendants should inherit the Hungarian throne without election, and if his line were to die out, the descendants of Emperor Charles V would follow. Only if both branches of the Habsburgs were to die out could the kingdom pass to János’s descendants, and only after both dynasties had died out could a free election of a king take place (point XL).

János Szapolyai’s coat of arms (reconstruction)

However, the treaty provisions also stated that after Ferdinand’s death, his firstborn son – the future Maximilian II – must be elected the country’s king “by common consent” (point VII). This latter provision naturally contradicted the former, which suggested automatic inheritance for Ferdinand’s descendants, a point already established by the historian and former canon of Nagyvárad, Vilmos Fraknói.

To proclaim the provisions of the peace treaty, a diet was to be convened, to be attended by the estates under the rulership of both kings, and at which a single palatine was to be elected in order to symbolize the unity of the country. At the same time, however, it was decreed that other state officials (chancellors, magistrates, chamberlains, treasurers, judges, and others) should be appointed by the respective kings in their own courts according to their dictates. The provisions also stipulated that decisions regarding the situation in the country and the restoration of peace should be made at the next general diet (point XLII).

The treaty also included provisions regarding the issue of an anti-Turkish alliance, with King János renouncing his alliance with the Turks and promising not to maintain it in the future, although he could inform the French king, as his ally, about the peace terms that had just been concluded (point III). Both kings were aware that if the peace terms became public, a counterattack could be expected from the Ottoman side. This is why the text of the agreement included a provision that if an enemy were to attack the country, it would be met with a united force and that Ferdinand would declare a diet and a military uprising.

Consequences of the treaty

Once the agreement had been reached, János withdrew to the eastern territories, and although the peace treaty was to be kept secret from the Sublime Porte, it was expected that the truth would eventually come out – and so it did. In 1539, the traitor Hieronymus Łaski, who had sided with the Habsburgs, informed the sultan’s court about the agreement. This did not have any immediate or serious repercussions, although political figures in János’s camp feared the sultan’s next campaign would be directed against Hungary.

The first occasion on which Ferdinand could have spoken about the Várad peace terms, which had been kept secret from the nobility living in the western parts of the country, would have been at a gathering convened in Pozsony on June 29, 1538, where, unfortunately, only a handful of nobles and representatives of only five counties appeared.

The terms of the treaty were not discussed here, and their ratification took place neither here nor at the subsequent diet of Bratislava in September 1539, at which Ferdinand finally informed his supporters about the treaty.

The only portrait of János Szapolyai considered authentic – a woodcut by Erhard Schön, late 1530s

The Hungarian estates rightly complained at this diet that they had not been allowed to participate in the peace negotiations, nor did they approve of the agreement, for they believed it would lead to the country’s division. In fact, the Hungarian estates gathered in Pozsony were so opposed to the agreement sanctioning the country’s division that they decided to hold a meeting with the pro-János nobility in order to defend the country together.

Ferdinand, responding to the Hungarian nobles, strongly opposed and even forbade their holding a joint diet with the pro-János nobility and explained that he had concluded the Treaty of Várad in order to restore national unity and reassured his advisors and followers who were present that he would be pleased to involve them in further negotiations later at an appropriate time. Ferdinand signed the Treaty of Várad on June 10, 1538, in Wrocław, with Charles V following suit later in Toledo.

The Várad agreement did not bring any real peace to the everyday life of the country. János’s supporters, including Menyhért Balassa, Ferenc Bebek, and Rafael Podmaniczky, invaded the territories under Habsburg rule and seized parts of them. According to the Habsburg faithful, these actions may have been motivated by Friar György, who was hoping to expand his king’s sphere of influence and gradually oust Ferdinand from the country. The former lord lieutenant of Hont County, Ferenc Nyáry of Bedeg, kept a record of a meeting in February 1539 attended by King János and Friar György. According to this source, Friar György argued that the Treaty of Várad could only be considered an agreement with full legal force if it were accepted by the entirety of the Hungarian estates, regardless of their affiliation, at a general assembly of the estates.

King János did not break the treaty he made with Ferdinand by marrying and having a son, but he did break it by willing on his deathbed in Szászsebes (Sebeș), in June 1540, that his chief advisors protect his son’s interests and preserve the kingdom for him no matter the cost. It is not by chance that the historian Farkas Bethlen noted that with the death of János, “the unconfirmed and unpublished Treaty of Várad also lost its validity.” The struggle for Hungarian kingship began anew under new circumstances and partly with new actors, while the Treaty of Várad served as the basis for a tug-of-war between the Transylvanian princes and the Hungarian kings for the next century and a half.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)