Mundus se expediet – the world will find a way out! In the winter of 1944/45, Hungary – along with the rest of the world – faced an apocalyptic situation and was actively seeking a means of escape, despite enormous difficulties. Hiding and waiting things out were no longer an option: a stand had to be taken. There were those who wanted to fight to the bitter end and others who wanted to strike out on a new path. The latter were behind the establishment of the Provisional National Assembly and the Provisional National Government in Debrecen.

There is already a rather extensive literature on the creation and operation of the Provisional National Assembly and the Provisional National Government. Thus, this article does not intend to examine the circumstances regarding the formation of the parliament and the government nor to analyze either governmental decrees and debates or parliamentary legislation and sessions. There is almost full agreement that this government originated in Moscow. Then-Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov even admitted as much when he stated: “I created this government.” But this was at a time when the interests of the main Western allies were still being taken into account – at least to some extent. Since preparations for the new government had begun in October 1944, the primary concern was detaching Hungary from its military alliance with the Greater German Reich and thus facilitating the Soviet advance into the Carpathian Basin.

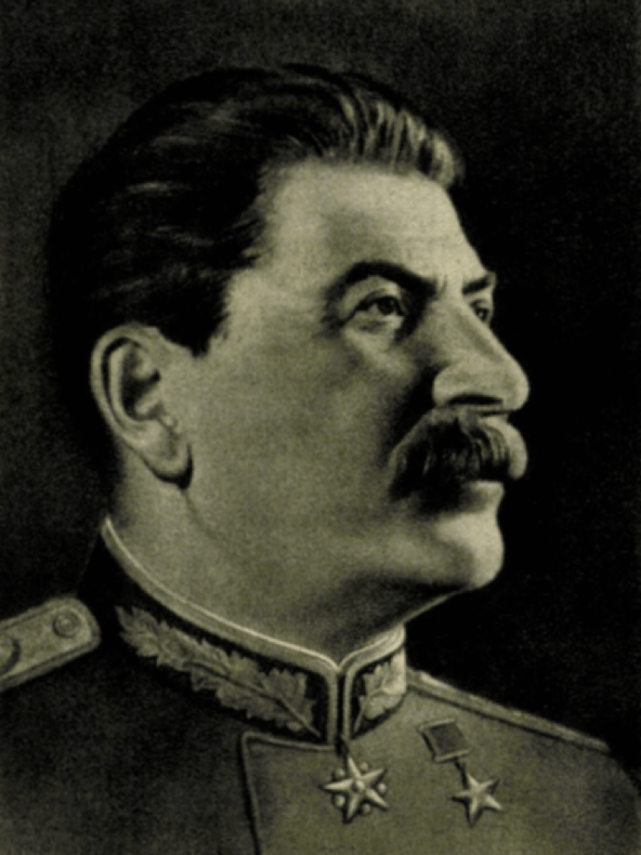

Stalin is given a free hand

It should be noted that Regent Miklós Horthy had already sent his own armistice delegation to Moscow at this time, having arrived there despite serious adversities, in order to break away from the Third Reich (announced on October 15, 1944). As known, this attempt was unsuccessful. This was also when the infamous Churchill-Stalin meeting took place in Moscow, between October 9 and 18, 1944, during which Great Britain – with the agreement of the US – “rewarded” the Soviets for switching sides, that is, for joining the Allied side, by surrendering Central Europe and offering it to Stalin and the Soviet Union on a platter. (Thus, despite conflicting accounts, this did not happen at Yalta.) Hitler refused such a generous offer in November 1940 when Molotov submitted his new demands during the German-Soviet Axis talks. The Churchill-Stalin agreement meant that the occupying Soviet forces were essentially given a free hand in Eastern Europe, including in Hungary, with only a few “disputed” areas left unresolved, such as Greece, Austria, and Germany itself. The fate of these areas would be determined by civil war (Greece), compromise (Austria, but only ten years after the end of the war), or “peaceful” partition (i.e., the division of Germany into two).

Such were the complicated conditions in which the Provisional National Assembly and Provisional National Government prepared for their existence in Moscow. Three groups seemed potential partners to Molotov: the Hungarian armistice delegation, those military officers who defected on October 15, and the large number of Communist émigrés then living in Moscow. Of decisive importance was the fact that in Hungary’s case – unlike that of Poland, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia – there could be no talk of a Western émigré government or even significant numbers of émigrés in the West. Hungary’s fruitless effort to switch sides meant that elements of the past would be unable to survive, unlike the monarchy in Romania.

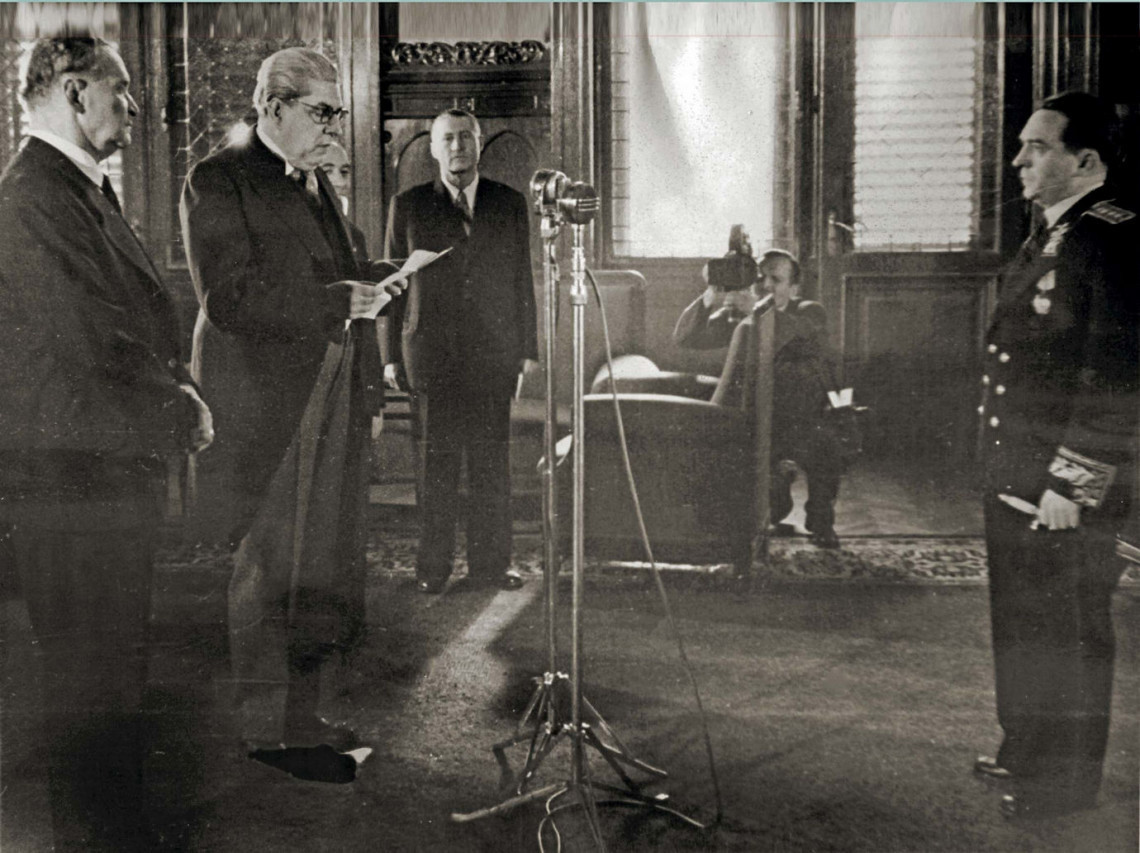

Following the failed armistice, the most important group among the Hungarians became the military officers’ group due to the Arrow Cross government’s policy of resistance. This explains why Colonel-General Béla Miklós was positioned at the head of the provisional government, with two other generals also participating in the government. The Soviet goal was to break Hungarian military and political resistance and facilitate a rapid Soviet advance so that the Red Army could reach the territory of the Third Reich still in 1944. Thus, by the winter of 1944/45, the main goal for the USSR was not the rapid Sovietization of Hungary and its integration into the Soviet empire but to break the country’s military resistance.

The situation may have seemed clear-cut, but it was not, mainly due to the German occupation. The country became a battlefield, resulting in civilians and soldiers alike enduring immense suffering from the fall of 1944 to the spring of 1945. All of this also had an impact on the Soviet occupiers as their brutality and mercilessness reached unimaginable levels. It also changed the attitude of the Kremlin’s leaders. As for the Provisional National Assembly and the Provisional National Government, they had failed in their most important task – to shorten the war and the attendant suffering. They also failed to resolve Hungary’s dangerous political and international isolation. And finally, they failed to create the conditions for lasting democratic development.

What caused this? It was partly due to the Soviet occupation and partly due to the fact that the victorious Western allies were forced to recognize Stalin’s Soviet Union as a “democratic state.” This lie proved fatal for the countries of Central Europe, regardless of whether they emerged on the winning or the losing side. As in World War I, a “positive goal” loomed before the advancing Western allies – a democratic system – but they could only win with the help of the Soviet Union (or at least achieve victory with far fewer casualties). Thus it followed logically that this positive goal – a democratic system – also became a virtue of the Soviet Union. There was no escape from this trap, either for Hungary, Czechoslovakia, or Poland, where there were historical traditions and demands for a genuine, European-style democracy.

It was Soviet Marshal Kliment Voroshilov who informed Béla Miklós what constituted democracy. As chief plenipotentiary of the Allied Control Commission (ACC) he expressly chose to separate military and civilian oversight. He put it this way: “Since Soviet occupation troops are currently in Hungary, [the Soviet High Command – K. Sz.] will continue to announce its demands regarding supply. The ACC will not interfere with this.” These “demands” could be used to squeeze the Hungarian government to the limit. Moreover, most of the competencies of the Provisional National Government were curtailed during the frontline fighting, when essentially all decisions (seizure of factories, roads, and railways, deportations, and plundering of the countryside) fell within the purview of the front commanders, city commanders, and the like. The logic of the situation meant that no real assistance could come from the “West” as more important matters still needed to be concluded, none of which were effectively resolved either (Germany, Persia, China, Japan, etc.).

Democracy without democracy

The Provisional National Assembly did not reflect the true political will of the Hungarian nation, with the so-called left-wing parties overrepresented in the chamber. No real elections took place either, most just adhering to appearances. The legitimacy of the Provisional National Assembly was extremely tenuous in this respect, and the body as a whole lacked authority. At its inception on December 21, 1944, almost 58% of its members were either members of the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) or the Social Democratic Party (SZDP). Regardless, the National Assembly had symbolic importance at most, meeting for only two days in December 1944 and unable to convene again until September 1945 in order to approve the government’s most important measures. This amounted to a grand total of 28 hours of deliberations, with debate taking place over only one bill – the suffrage law.

The Allied (Soviet) Control Commission prevented more frequent meetings. Instead, the Political Committee of the Provisional National Assembly took charge of matters. The “democratic” parties of the Hungarian National Independence Front participated both publicly in the national assembly and behind the scenes in the government’s backrooms. This raises another salient question: Were these parties truly democratic? The answer is no. The two parties in question, the MKP and the SZDP, had already closed ranks as early as October 1944, agreeing on the joint goal of establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat, eliminating parliamentary democracy, establishing socialism, and uniting the two parties into one. The leadership of the National Peasant Party (NPP) also joined this grouping, forming the Left Bloc. The activities of this alliance led to the end of the Hungarian experiment in democracy. Thus, the goals of these parties were far from democratic.

The practice of “democratic centralism” had instilled a sense of military discipline towards the leadership within the Communist Party, but neither the Social Democratic Party nor the National Peasant Party operated on democratic principles either. The leadership of the various parties stifled internal party life, expelled those who disagreed, and then tried to “criminalize” the latter through false accusations and show trials. The cases involving Károly Peyer of the SZDP, Imre Kovács of the NPP, and others later provide relevant examples. The rival Smallholders’ Party (FKgP), meanwhile, although democratic in terms of its goals, had also ceased to be so regarding its internal life, as those who disagreed with the positions of the party leadership were expelled or denounced (Dezső Sulyok, Zoltán Pfeiffer, István B. Szabó, etc.).

All of this is important if only to establish that there was no real national democratic party support behind the government, much less a democratic international background. Hungary was occupied by a power that was intent on establishing a dictatorship, one based on imperial logic. Hungary was a defeated, subjugated state where the central authority of the occupying forces (ACC) enjoyed full power, as did its local bodies, the city commandants – who appointed the respective mayors – and the factory commanders. Under such circumstances, it would have been unrealistic to expect the government to establish a successful democratic framework – and yet the intention had been there originally among the majority of the government.

A few names should be mentioned at this point. The first is one of the most outstanding figures of Hungarian national democracy, István Vásáry, who originally served in the Béla Miklós government as minister of finance. Vásáry also served as chairman of the Preparatory Committee of the Provisional National Assembly and was the first to address the National Assembly on December 21, 1944. Among other things, he said: “The Hungarian people never wanted this war! They were forced into this war without asking.” The House concurred. The government also included Géza Teleki, son of the former prime minister Pál Teleki, who served as minister of culture, and Ágoston Valentiny, a true social democrat of European standing, as minister of justice. It is interesting to note that István Vásáry, Béla Miklós, and Béla Zsedényi, who was elected speaker of the National Assembly, were all nominated for their positions at the request of the Russians.

When the Provisional National Government was reorganized on July 21, 1945, Vásáry and Valentiny were left off the list, along with the former minister of public works, Gábor Faragho, and the former industry minister and SZDP member, Ferenc Takács. This marked a decisive turning point as national and democratic interests were now substantially reduced in importance. Alongside the communists, there were political figures – members of the social democratic and peasant parties – who were widely known to be “political realists” and even “cryptocommunists” (Sándor Rónai, István Ries, Antal Bán, and Imre Oltványi) and would collaborate with Rákosi’s party to the very end. This development clearly showed that the tasks of the Provisional National Government had now changed; now that the war was over, the original goals were no longer relevant. The main thing now was to establish party positions.

Government by decree

The Provisional National Government ruled by decree, using this method to implement land reform. Few doubted the need for land reform, but was this the way to do it? – With holdings reduced to unviable sizes and the brutal liquidation of the entire aristocracy? This decision served primarily political purposes – not economic interests. It was also intended to lay the groundwork for collectivization. At the same time, this decision was also intended to hasten the defection and desertion of Hungarian soldiers still fighting on the opposing side.

A framework for accountability had also been established. Almost everyone agreed on this. But was this the way to do it? – By means of party courts (People’s Tribunals)?

The government also decreed a new suffrage law, which the National Assembly approved. This was also necessary. But again, was this the way to do it? – With only the governing parties essentially able to run? – With no significant opposition? – With Christian democratic, conservative, and other parties unable to compete?

The provisions of public administration were changed. But was this also the way to do it? They restructured the organization but did not allow local elections. Instead, rural municipal authorities were established on a “parity” basis, with all parties obtaining equal representation, thus ensuring the Left Bloc a majority everywhere until the introduction of the council system in the 1950s.

The provisional government declared war on Germany in December 1944 but did not request prior approval from the National Assembly. And when the National Assembly subsequently approved this decision in September 1945, neither Hitler nor Germany existed. That same fall, the political trial of the former Hungarian prime minister, László Bárdossy, began, one of the main charges against him being that he did not ask prior approval from the National Assembly for the war against the Soviet Union and only did so long after the state of war had been declared.

The Provisional National Government concluded an armistice, but did it have to be like this? – With the country incapable of even assembling an army? The ACC also determined how large the Hungarian army could be on paper, although Béla Miklós considered this to be illegal. This number was 25,000 men.

The government also banned “far-right” organizations, but did it have to outlaw the entire former ruling party, for example?

They were also occupied with the issue of Hungary’s head of state, but the question of the form of government was left for later. Horthy had been deported by the Germans in October, and his name was removed from relevance. A collective body called the High National Council was instituted until the adoption of a republican form of government on February 1, 1946. The Provisional National Government had almost no contact with the West, having more engagement with the Soviet occupiers. The country endured the presence of both the Soviet Army and the Allied Control Commission. The Provisional National Government recognized their right to reparation shipments and the dismantling of factories and other enterprises, as well as border changes effected in accordance with the armistice. This did not presage well for Hungary in the peace negotiations.

The Provisional National Government concluded the Soviet-Hungarian economic agreement (not the same as the reparations agreement) on August 27, 1945, thus clearly tying the Hungarian economy to the Soviet Union. The agreement was signed in Moscow by Ernő Gerő, a Communist member of the High National Council, without authorization. It provoked a storm of controversy. Prime Minister Béla Miklós submitted a written objection against it, as the agreement essentially handed over the entirety of the Hungarian economy to the Soviet Union through joint ventures, etc. The majority of the government was also against it, but “realpolitik” triumphed again: “Let’s not irritate the Soviet Union.” Hungarian factories and companies were placed under the “guardianship” of the Red Army until July 1945; the railways were returned only in October; and the industrial sector was released from direct obligation to supply the Red Army only in November. The economic agreement should have been ratified by the new parliament elected on November 4, 1945, but this was circumvented; instead, it was done by the High National Council under the aegis of the Communists and collaborationist Smallholders. None of this, however, earned any “goodwill” from the Soviet Union; instead, it left the Hungarian economy enthralled to the great eastern empire for forty years.

Opportunities and possibilities

The Provisional National Government assumed power over the country at a time when it was obvious that the Soviet Empire was extending its reach into Central Europe, including Hungary. This limited its options from the outset. The fact that the West was militarily and politically absent or represented only to a minimal extent in the region further restricted the government’s room for maneuver. Thus, lacking sovereignty, the goal could only be the fulfillment of expectations. But what were the expectations? And here the question is worth asking: was everything indeed decided in Tehran when it became clear that the Western invasion would not take place in the Balkans but in France? In Moscow, when Churchill cynically proposed splitting up Central Europe – Budapest, Prague, and Warsaw – with Stalin by percentages? Was everything in fact decided the moment the Soviet Army invaded Hungary? And is that when the Communist reign of terror began? The answer is no, not entirely.

No, because Moscow retained Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Finland as large bargaining chips. In these countries – and only in these – partially free elections were held and civic, Christian, democratic forces were able to form majorities in parliament – as occurred in Hungary. Of course, this also meant that as early as late 1944 and the very start of 1945 the Soviet occupiers were already seeking to establish those positions which they saw as guarantors for the later enforcement of their interests and the impeding of hostile interests: hence, the appropriation of the political police, the plundering of the economy and then its subordination to imperial interests, the placing of conditions on the administration of justice, the establishment of a party system, and so on.

The issue of the political police, which had been completely appropriated by the Communist Party with the assistance of the invading Soviet forces, proved decisive. Gábor Péter, head of the political police in Budapest, even explained to his rival – and fellow communist – András Tömpe, who had been “authorized” by the Provisional National Government in Debrecen to establish a political police department, that no one in Budapest recognized the Provisional Government. The Soviet political police (NKVD–People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) and the Soviet military court (Military Tribunal of the Soviet Central Army Group) were active throughout Hungary. Tens of thousands, or rather, hundreds of thousands, of people were deported to the Soviet Union for slave labor. Twelve members of the Provisional National Assembly were even taken into custody, among others. Under such circumstances there could be no talk of legality. It was for this reason that the justice minister, Ágoston Valentiny, who wanted no part of this, was dismissed.

And yet, there was a window of opportunity. This was prior to when the West and the Soviet Union had become mortal enemies, which happened in the winter of 1946 – or spring of 1947 at the latest. There were countries that were able to take advantage of this opportunity: Finland and Austria. There were others, such as Greece, where the West intervened militarily. However, the Cold War had still not fully arisen during the mandate of the Provisional National Assembly and the National Government, and cooperation among the three great powers still seemed intact at this point.

How would this opportunity have arisen? – Only if Europe had acted in concert against Soviet ambitions. If a United States of Europe had already been realized at that time, then Prague and Budapest would have been at least as important for it as Paris and London. It did not happen, but it was not solely Hungary’s fault. The United States could have countered Soviet expansion, but American power and ambition were limited to saving Western Europe, the Far East, and Greece. There could have been another possibility – the unity, alliance, and mutual resistance of the peoples of Central Europe. But this was an illusion after the incredibly foolish decisions that ended the First World War, and the course of the Second World War did not help matters either. Following the Second World War, there were abortive attempts at a Hungarian-Romanian customs union, Czechoslovak-Hungarian cooperation was discussed, and Tito’s various conceptions of a Central European federation were also on the agenda. There was even talk of Bavarian-Austrian-Hungarian neutral zone, but nothing came of this either. Instead, there was hostility, displacement, population exchanges, assimilations, “non-aligned” communism, and so on.

In September 1945, the Provisional National Assembly ratified the government’s decrees, and national assembly elections were held in November on the basis of Act VIII of 1945. The existing provisional government thereupon resigned on November 15, 1945. Béla Miklós noted that the new government’s “only remaining task with respect to the democratic order is to further develop the established democratic discipline and apparatus and to defend it from attacks from all sides.” As is known, this effort failed – and not because of the fascist threat that the communist and other left-wing newspapers warned of on a daily basis, but precisely because of the communists’ own aspirations.

In 1947, Béla Miklós became one of the leaders of the Hungarian Independence Party led by Zoltán Pfeiffer, as did Béla Zsedényi, the speaker of the Provisional National Assembly. Neither of them was willing to abandon their homeland. The former prime minister died of a heart attack in 1948 while the former speaker was arrested in 1950 and died in prison five years later due to a lack of medical care. The former minister of justice, Ágoston Valentiny, was also imprisoned from 1950 to 1955, as was the former minister of defense, János Vörös, from 1950 to 1956.

Returning to the original question – was there a possibility for a democratic Hungary in 1945? My answer remains yes – otherwise we would be exonerating those collaborators who betrayed and attacked this democracy and those purveyors of realpolitik who were incapable of fighting for it in a competent and courageous manner. To say no would mean erasing the last efforts of thousands of people and the well-articulated will of millions of Hungarians with the decrepit notion that everything had to happen the way it did “out of necessity.” To say no would mean forgetting the great struggle of those politicians, artists, public figures, priests and pastors, and farmers and workers who fought for democracy between 1945 and 1948. And it would also mean conflating the responsibility of those quislings of the dictatorship with the actions of those who fought for freedom. To prevent this from happening, let us remember in good conscience those who under difficult circumstances tried to steer Hungary’s destiny along a better path. Among these stood Béla Miklós, Béla Zsedényi, Dezső Sulyok, Zoltán Pfeiffer, István Vásáry, Ágoston Valentiny, and others. Although unsuccessful, the lessons learned then resonated in 1989-1990 and are of inestimable value even today. They risked their lives for Hungarian democracy; they fought for it and received prison, deportation, or exile as their reward, while others just shook their heads, saying: “You see the specter of communism even where there is none.” They were to be bitterly surprised.

Yes, the 80-20% split in favor of Soviet influence worked out in Moscow may have been unfavorable for Hungarian democratic interests, but were these grounds to give up? I don’t think so, not when the nation’s fate lay in the balance and not even if such slim chances that did exist were themselves – excessively optimistic.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)