In a supplementary declaration to the Munich Agreement of September 1938, Hungarian territorial claims against Czechoslovakia based on the ethnic principle were recognized as legitimate by all four of the great powers – France, Great Britain, Italy, and Germany.

However, the differences of opinion between the two interested parties – the second Czechoslovak Republic (after Munich) and the Kingdom of Hungary – prevented a negotiated settlement during talks held in Komárno (Komárom), Slovakia, between October 9 and 13, 1938. This led to the great powers issuing a decision known as the First Vienna Award.

Britain and France, signatories to the Munich Agreement, did not participate in this new great power decision, however. Nevertheless, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, recognized the Vienna decision as legally valid and fully in accordance with the Munich Agreement, but stated so only verbally.

Following the signing and enactment of the Treaty of Trianon, the Hungarian political elite of the time had to confront, at the same time, both the limited internal and external opportunities of their now independent country. This independence came at the price of a reduction in size, economic dependence on external trade relations, and military vulnerability with respect to the great powers and the European security system. While the country’s economic self-sufficiency was gradually restored, its army – limited to 35,000 men – would have been incapable of defending the post-Trianon territory against the countries of the so-called Little Entente (Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia), whose forces were ten times – in some cases twenty times stronger – and better equipped. It was for this reason that Prime Minister István Bethlen quickly put an end to various armed plans and adventurous ideas after coming to power, although representatives of the latter continued to appear from time to time on the dark fringes of Hungarian diplomacy.

Images worthy of a painting were repeated in every village during the Hungarian entry into southern Slovakia (Upper Hungary). The hardworking inhabitants of Hungarian villages, dressed in festive attire, awaited the arrival of Hungarian troops, whom they greeted with decorated gates, flags, and flowers. Many of the soldiers would remember this moment their entire lives.

Consolidation and creating room for maneuver

Both for all the above reasons and due to tense internal social contradictions straining the country, the main goal during the first decade and a half of the Horthy era was focused on consolidating the country and embedding it within the European balance of power. This involved creating political room for maneuver and finding great power support in an effort to protect the national interests of what was the second smallest state in Central Europe.

Hungary’s four main priorities in foreign policy were summarized by Prime Minister István Bethlen in a speech made in Debrecen on February 26, 1922: “The first is to restore economic equality along the entire spectrum and to establish economic relations with the neighboring states. The second is to postpone the question of reparations. Hungary is unable to pay reparations. The third is to protect the Hungarian minorities in the territories that have been torn from us. The fourth is to end the policy of intervention by joining the political trend that has put forward the program of European disarmament.”

Thus, the economic and domestic political criteria of the Bethlen consolidation were accompanied by realistic and practicable policies with respect to foreign trade, neighboring states, minorities, reparations, and security policies, which greatly contributed to the recovery and gradual development of what many considered an unviable post-Trianon state. Naturally, the need to obtain great power support as a policy tool was understood from the very beginning, since without this support, the border changes that were hoped to be achieved through merely peaceful diplomatic means would have been illusory.

The breakup of the Little Entente was also an important prerequisite of any realistic revisionist notions. Hungarian diplomacy took this aspect into account from the very beginning and tried to develop separate negotiating positions towards each of its three Entente neighbors. The Hungarian Foreign Ministry generally considered Yugoslavia to be a potentially weak link and directed most of its initiatives towards Belgrade. On the other hand, the situation with Czechoslovakia was the most tense throughout, and once Hitler came to power, there was no question that Hungarian revisionist demands had to be put forward most forcefully against Prague.

Ten days before the Anschluss, on March 2, 1938, Hungarian Foreign Minister Kálmán Kánya paid an official visit to Vienna, where he met with Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, who was in an increasingly hopeless situation due to Hitler's threats. For Kánya, who was committed to maintaining Italian-Austrian-Hungarian cooperation, the visit to Vienna was seen as a show of support for the Austrian Chancellor, who was attempting to avoid the horror of the Anschluss by calling a plebiscite on Austrian sovereignty.

The Munich Agreement of September 29-30, 1938, demonstrated to the Hungarian government that a European great power alternative for the revision of the Versailles territorial provisions existed within the context of European interwar politics and that such an alternative could accord with Hungarian interests. At the same time, the Munich Agreement also marked out Budapest’s foreign policy space. As an initial step, however, Hungary was limited to negotiations in asserting its ethnic-based territorial claims against Czechoslovakia.

Czechoslovakia in Hungarian revisionist policy

The initial optimal and ultimate goal of Hungarian foreign policy was a complete revision regarding the lost historical territories of northern and northeastern Hungary. But it was realized very early on that such a policy was unthinkable without international great power support.

Secret Franco-Hungarian negotiations in the spring of 1920 already made clear the position of the great powers regarding new Central European foreign policy. Instead of plans for military action against Czechoslovakia, first, Prime Minister Pál Teleki, and then, especially Prime Minister István Bethlen, placed emphasis on national consolidation while gradually developing the idea of a peaceful revision based on great power consent and support.

Bethlen saw the first encouraging signs of great power support for revisionist demands in the intensified Italian-Hungarian rapprochement in the mid-1920s, but he also pursued Hungarian revisionist goals with other great powers; it was especially important to Budapest to have them acknowledged firsthand and accepted by government circles in London. Kánya Kálmán, as an experienced diplomat and foreign minister to the Gömbös, Darányi, and Imrédy governments in the second half of the 1930s, placed great emphasis on having Britain and France – despite their obligations and treaties towards their Central European allies – show understanding and benevolent neutrality towards Hungarian revisionist aspirations.

Even during the months of the Czechoslovak crisis, the Hungarian foreign ministry tried to maintain daily contact with the leaders of British diplomacy, partly through the Hungarian ambassador in London, György Barcza, and partly through the mediation of Thomas Moore, a British diplomat who had previously served in Budapest. During Kánya's tenure as foreign minister, it was considered a particularly important task to simultaneously inform London and Berlin, Paris and Rome – and in some cases even Moscow – about the Hungarian government’s revisionist considerations. Meanwhile, the Hungarian foreign ministry tried to establish a new modus vivendi with the Little Entente. This was successfully achieved in August 1938 with the conclusion of the Bled Agreement, which provoked Hitler to violent outbursts directed at the Hungarian regent, Admiral Horthy, with whom he was holding discussions in Kiel. Kálmán Kánya himself was often openly and sharply attacked by Hitler for his policy of seeking to avoid German dominance and coercion, which eventually led to Kánya’s resignation at the end of November 1938.

The territorial goals of Hungarian revisionist policy were continuously clarified in the 1930s and its strategic and tactical elements expanded. For example, the objectives of minority protection, neighborly cooperation, and a more comprehensive yet still peaceful revision were consistently present in the Gömbös government’s program (1932–1936). Following the conclusion of the 1927 Hungarian-Italian Treaty of Friendship, Rome became Hungary’s most important great power supporter while also playing a role in the country’s rearmament. However, the terms of Central European cooperation outlined in the 1934 Rome Protocols, signed by Italy, Austria, and Hungary, did not meet with German approval. Gömbös’s trip to Berlin in June 1933, as the first foreign head of government to visit Hitler, clearly indicated that Hungarian foreign policy intended to strengthen its position in Central Europe by forging closer ties with the Third Reich. However, this quickly became the source of numerous bilateral and regional conflicts and fundamentally limited Hungary’s foreign policy space.

When the Czechoslovak Prime Minister Milan Hodža met with the ethnic Hungarian delegation led by János Esterházy during the first days of British Lord Runciman’s mission to Czechoslovakia, he clearly stated that the German question had absolute priority in the management of the crisis. Hodža openly explained that they no longer trusted their own strength and that they clearly saw that the fate of Czechoslovakia and the handling of the Czechoslovak crisis rested on the decisions of the opposing great powers: “The favorable resolution of the crisis lies in the hands of the Third Reich. The Third Reich is at a crossroads at present, and I dare hope that it will avoid any steps that could lead to a catastrophe. We are clearly aware that this is a purely German-British matter, so if the Third Reich shows any relaxation in its attitude, it will be entirely due to British influence.”

The Czechoslovak crisis was incapable of any internal resolution in September 1938. President Beneš could only hope that the British and French would realize that Hitler could not be stopped with temporary concessions. During the Czechoslovak crisis, Hungary had a fundamental interest in ensuring that the same principles be applied in resolving the situation of the Hungarian minority as in the case of the Sudeten Germans. The Darányi government kept the idea of reacquiring the whole of Slovakia on the agenda until May 1938, and in April it even queried the position of the German Foreign Ministry leadership and Hitler himself in this regard. For example, the Deputy Foreign Minister Gábor Apor gave the following unusual directive to Ambassador Sztójay in Berlin: “We would be grateful to Ribbentrop if – recalling the Reich Chancellor’s statements of that time [November 1937] – he were to be kind enough to inform him in this regard that the Hungarian government has the firm intention of granting broad autonomy to the Slovaks and Ruthenians living in Slovakia (Felvidék) in the event of its reincorporation.”

The role of Germany and Italy

The focal point of Mussolini and his foreign minister Count Ciano’s plans for Central Europe was Austria under Engelbert Dolfuss, who became chancellor in March 1932. The chancellor, who ousted the social democrats from power and then liquidated the leftwing party after civil war broke out in February 1934, worked closely with fascist Italy. Under the “bureaucratic” state model known as Austrofascism, patterned after Italian fascism and introduced by Dolfuss, all political parties were dissolved. The Rome Protocols of March 1934, however, did not put an end to German-Austrian conflicts, nor was Dolfuss able to make Austrian public opinion accept the new Italian orientation. At the same time, he openly opposed Hitler’s increasingly publicized Anschluss aspirations. All of this indicated that Italy’s ideas for Central Europe – especially after the Anschluss of March 1938 and the Blumenkrieg that saw Hitler’s arrival in Vienna and Austria’s incorporation into the Reich – were on very shaky ground. Hungarian diplomacy also accurately perceived this but continued to strive to secure Rome’s support for Hungary’s revisionist goals.

In the Europe of that time, revisionist demands similar to those of Hungary were put forward by only one great power, namely Germany. Although Germany’s Weimar Republic was interested in the gradual dismantling of the Versailles peace system from the start, issues regarding territorial reorganization in the East Central European region remained on the backburner throughout the Stresemann era. For Budapest, however, Germany was the decisive power in terms of revision from the very beginning.

From the early 1930s, Berlin began placing greater emphasis on improving the legal and political situation of German ethnic groups abroad. In the same vein, they were also dissatisfied with the situation of the German minority living in Hungary, which they communicated quite clearly to the Hungarian prime minister, Kálmán Darányi, during his visit to Berlin in November 1937. It is no coincidence that from this time on, in addition to Hungarian minority issues, the Hungarian government department of minorities, headed by Tibor Pataky, had to pay increasing attention to the issues raised by ethnic Germans in Hungary.

Hungary, in turn, accused the German minority parties and political leaders in Czechoslovakia of maintaining their distance from the Hungarian minority parties. On February 10–12, 1938, at the initiative of the Hungarian government, two leaders of the Sudeten German Party, Karl Herman Frank and Franz Künzel, met in Budapest in an attempt to coordinate their actions with the leaders of the United Hungarian Party in Czechoslovakia, János Esterházy and András Jaross, and to obtain effective support for this from the Hungarian government.

In his report to the Berlin Foreign Ministry on February 19, 1938, Künzel emphasized that during their negotiations in Budapest with two former prime ministers – István Bethlen and Kálmán Darányi – and with Foreign Minister Kálmán Kánya, they both realized how foreign the ideology of the Sudeten Germans was to Hungarian politicians and that the latter viewed Hungarian revisionist aspirations almost exclusively “from the perspective of the crown rights of Saint Stephen.” In any case, the rising importance of the Sudeten German issue along with the increasing strength of Slovak autonomist aspirations alerted Hungarian diplomacy to the fact that Berlin was considering the ethnic solution as an increasingly important tool in resolving the Czechoslovak question.

Starting in 1937, the Hungarian government tried to clarify the obligations incumbent upon Hungary with respect to German military plans against Czechoslovakia. By the spring of 1938, the Hungarian general staff was already faced with the risks of constantly changing German plans. In May 1938, Major Fruck, the agent for Admiral Canaris, Germany’s counterintelligence chief, met with Rudolf Andorka, the head of the 2nd department of the Hungarian general staff, which also dealt with counterintelligence, in order to clarify how Hungary would enforce its own demands in the event of either a peaceful solution to the Sudeten German question or German military intervention. It is clear from Andorka’s report on the visit that the Hungarian military leadership was fundamentally interested in a peaceful solution due to the unpreparedness of the army and the threat of a possible attack on the part of the Little Entente.

The notion of a fundamental revision

Preparations for a fundamental revision of the postwar borders were present throughout the 1930s at both the bilateral and regional levels of Hungarian government policy. In the case of Czechoslovakia, this would have meant the voluntary “return” of what had been formerly Northern and Northeastern Hungary, i.e., the entirety of then-Slovakia and Ruthenia. In Budapest, it was hoped that the Slovak and Ruthenian elites had had their fill of Prague’s centralizing policies of the 1920s and its rejection of the autonomy aspirations expressed by the two “indigenous” peoples. It was believed that a promise of broad powers of self-government within Hungary would entice these two peoples to readily join a Hungarian state framework rejuvenated in the spirit of Saint Stephen.

Hence, the reason why Hungarian government policy did not embrace the notion of Hungarian autonomy within Czechoslovakia until 1938 was because the Hungarian political elite long considered it unthinkable that the Slovaks and Ruthenians would not opt for a return to Hungary as the most attractive solution for gaining their own autonomy. This was essentially the purpose of the so-called “indigenous” concept of Budapest government policy. For a while, it seemed reasonable that Hungarian-Slovak-Ruthenian-German cooperation could be established in Slovakia and Ruthenia against the “invading” and “conquering” Czechs, Czechoslovak governments, and Czechoslovak parties. However, successive Czechoslovak governments in the 1920s managed to stabilize the country’s internal and external policies, and in 1928, the first Czech-Slovak-German coalition government was formed, which rendered ineffective the Hungarian government’s indigenous-based policy.

Naturally, Budapest was fully aware of the opposition of both the Little Entente countries and British and French policy regarding a thoroughgoing revision of the postwar borders while also taking into account other diplomatic and military obstacles. That is why, starting in the 1930s, the leaders coordinating Hungary’s revisionist foreign policy in the Foreign Ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office came to increasingly rely on the possibility of an ethnic revision aimed at the return of Hungarian-majority areas.

In the early 1930s, Andrej Hlinka, the leader of the increasingly autonomous Slovak People’s Party (HSL’S), and the younger generation of HSL’S members who had grown up alongside him, such as Jozef Tiso, Karol Sidor, and Ferdinand Ďurčanský, progressively envisioned the ideal scenario of Slovak autonomy within Czechoslovakia. Following Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the intensification of the Sudeten German issue in Czechoslovakia after 1935, Hlinka and his colleagues temporarily returned to the idea of forming a German-Slovak-Hungarian autonomous bloc within Czechoslovakia. With Reich support of the Sudeten Germans rethought on the basis of Hitler’s ethnic group principle becoming increasingly strong in the second half of the 1930s, the Hungarian government and the leaders of the Hungarian minority party in Czechoslovakia began to ponder the risks of cooperating with the Germans.

Following Hlinka’s death in August 1938, the autonomy aspirations of the HSL’S, now led by Jozef Tiso, also contributed to an escalation of the Czechoslovak crisis. Hitler’s increasingly intemperate actions against Czechoslovakia in the months leading up to the Munich Agreement threated to ignite a European war. In August 1938, in Kiel, the Hungarian regent, Admiral Horthy, managed to sidestep Hitler’s suggestion that Hungary should attack Czechoslovakia first in order to achieve its comprehensive revisionist goals.

During the diplomatically tense period of the Czechoslovak crisis, in September 1938, when Lord Runciman was engaged in negotiations in Prague, the chances of Slovak-Hungarian cooperation had practically disappeared. This was partly due to the efforts of Milan Hodža, appointed Czechoslovakia’s first ethnic Slovak prime minister in 1935, to win over Slovak autonomists. The decisive reason, however, was the handling of the 1938 Czechoslovak crisis and its repeated oscillations according to Hitler’s script.

Hitler’s original plan, the military action set forth in Case Green (Fall Grün) and its unpredictable consequences, which threatened a world war, was temporarily shelved by the four-power Munich Agreement. The agreement, signed in the early hours of September 30, 1938, by Hitler, Mussolini, Daladier, and Chamberlain, and known in Czech and Slovak historiography as the Munich Diktat, gave Germany possession of those territories of Czechoslovakia which had a German-majority population according to the last Austrian census in 1910, as well as the Slovak town of Devín (Theben), a borough of Bratislava, and the village of Petržalka (Engerau), located opposite Bratislava on the right bank of the Danube. Germany thus acquired a total area of 41,098 km² with 4,879,000 inhabitants, 15% of whom – roughly 800,000 people – were of Czech nationality.

With the annexation of the Sudeten German territories, Prague lost not only the Czechs living there but also the military fortifications it had built up along the Czechoslovak-German border, thus leaving the country almost entirely at the mercy of Berlin. Prime Minister Hodža and President Edvard Beneš resigned and went into exile. In early October 1938, a radical internal restructuring of the Czechoslovak state was undertaken, which saw the bestowing of autonomy on Slovakia and Transcarpathia in an attempt to resolve the crisis which threatened to bring about the country’s collapse.

Nevertheless, the Second Czechoslovak Republic’s external diplomatic situation remained critical. Poland swiftly exerted its own claims to 869 km² of primarily Polish-inhabited Czech-Silesian territory in the Těšín district in the form of a ten-day ultimatum. The situation that had developed by October 1938 from the Hungarian perspective meant that the idea of the whole of Slovakia returning to Hungary had been conclusively shelved.

Despite everything, the leading Slovak politicians of the time were still committed to a solution within what remained of Czechoslovakia. In early October 1938, the Slovak politician Pavel Farkaš, at the request of Jozef Tiso, head of the HSĽS, made a secret trip to Warsaw and Budapest in order to inform the Polish and Hungarian governments about the circumstances surrounding the establishment of Slovak autonomy within the Second Czechoslovak Republic. During Farkaš’s meeting with the Hungarian foreign minister, Kálmán Kánya, attended also by the former prime minister and current minister of religion and education, Pál Teleki, the head of the prime minister’s Department of Minority Affairs, Tibor Pataky, and the executive chairman of the United Hungarian Party in Czechoslovakia, János Esterházy, the Hungarian politicians suggested in vain that the whole of Slovakia should join Hungary in the event Czechoslovakia were to break up. Two days later, on October 6, 1938, in Žilina (Zsolna), the HSĽS decided to proclaim Slovak autonomy within the Second Czechoslovak Republic. The Slovak and Transcarpathian autonomous entities established after the signing of the Munich Agreement initially looked to Prague for the most favourable solution regarding their status, but from January 1939 onwards, they turned increasingly toward Berlin.

The additional protocols to the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement set Hungary’s revisionist policy in a new direction. Instead of his “big solution” of eliminating Czechoslovakia in a single step through war, Hitler regarded the annexation of the Sudeten German territories and the resolution of the Slovak and Ruthenian question in the form of autonomy within Czechoslovakia, in other words, the diplomatic imposition of ethnic-based changes to be a preferred temporary expedient. During the critical October days between the Munich and Vienna decisions, the Hungarian ambassador in Berlin, Döme Sztójay, drew his minister’s attention to the fact that the changes that had occurred in German-Czech-Slovak-Ruthenian relations were such that they could make it difficult to represent Hungarian interests effectively.

Sztójay, who basically approached things from a Berlin perspective and according to German interests, opined that instead of resolving the issue, Munich had made things more complicated: “However we consider the situation, from our perspective the ‘big solution’ would perhaps have been preferable, even at the cost of war, to the ‘small solution’ with all its complexities and unresolved questions.” Sztójay’s single-minded focus, unable to see Hungary’s vulnerability in relying solely on an aggressive major power within the unfolding history of Central Europe, unfortunately proved contagious among the Hungarian elite.

The Munich Agreement included a supplementary declaration in which the representatives of the four great powers provided the following regarding the Hungarian and Polish question in Czechoslovakia: “The heads of the governments of the four powers declare that the problems of the Polish and Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia, if not settled within three months by agreement between the respective governments, shall form the subject of another meeting of the heads of the governments of the four powers here present.” This was undoubtedly an important result of the Hungarian government’s efforts in September 1938, during which the regent, the government, and especially Foreign Minister Kánya and the Hungarian diplomatic corps mobilized all their envoys in the capitals of the Western powers to ensure that the issue of the Hungarian minority in Czechoslovakia was clearly expressed in the wording of the four-power treaty.

Ethnic revision gains prominence

Hungarian diplomacy initially attached less importance to an ethnic-based revision – border changes based on nationality – regarding it as a temporary expedient. Nevertheless, at the bilateral Hungarian-Czechoslovak talks that took place in Bruck, in Austria, and Mariánské Lázné (Marienbad) and Brno (Brünn), in Czechoslovakia, in 1921 and almost every year thereafter, notions and proposals were raised concerning border changes along the Ipoly (Ipel’) River and the Csallóköz region of southern Slovakia. These were seen as laying the possible groundwork for ameliorating the openly hostile relations between the two countries. Thus, every time Czechoslovak President Masaryk raised the prospect of ceding the Csallóköz or other Hungarian-majority areas, it elicited a lively response in Hungary.

Despite the primacy given to a complete revision of the postwar border system, demands for ethnic-based border changes were a constant feature of Hungarian government policy with respect to the Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Hungary tried to exploit the possibilities offered by the minority protection system, although Budapest made it repeatedly clear to the Hungarian minority leaders that it considered a territorial revision to be the optimal solution. The realities of the Central European nation-states between the two world wars, however, increasingly hindered the realization of the revisionist ideal as based on three criteria – historical, ethnic, and territorial.

Reintegration into the pre-1918 Hungarian state proved to be as unrealistic an idea as that of a Habsburg restoration. Likewise, there was no substantive basis for the creation of a common Hungarian-Slovak state, let alone the establishment of Slovak autonomy within Hungary. Nevertheless, this remained a prevailing notion in the revisionist plans for what was considered “Upper Hungary,” with some leading Hungarian politicians adhering to it until 1938. For a long time, Hungarian diplomacy placed great emphasis on the Hungarian minorities having the right to territorial self-determination alongside that of other “oppressed” peoples of the region, including the Slovaks and Ruthenes most of all. It was hoped that the majority of these two national communities, obtaining their own say about their future, would envision their self-determination unfolding within the context of the Hungarian state.

Although all the leading foreign policy figures of the day were forced to confront the foreign, geopolitical, and military considerations arising from the realization of revisionist goals, Hungarian decision-makers could not and did not want to miss out on the opportunity of border revision presented by Germany in the wake of the Anschluss and the 1938 Czechoslovak crisis. However, although the Hungarian government managed to avoid the thankless role of initiator of a military conflict, it was unable to rewrite the rules of Hitler’s scenario.

Hopes and dilemmas

The autonomous Slovak government formed as a result of the Munich Agreement tried to reach an understanding with the Hungarian delegation led by Kálmán Kánya and Pál Teleki during the Komarno talks in October 1938. The Czechoslovak delegation, led by the now-prime minister of the Slovak autonomous region, Jozef Tiso, tried to evade the Hungarian suggestion of ethnic-based border changes, raising instead the issue of securing autonomy for the Hungarian minorities in Slovakia and Transcarpathia, the solution of a reciprocal minority policy between the two countries, and even the idea of a population exchange. The Slovak government’s interests, however, were better served by exploiting the Munich decision, and presenting it to the Slovak public as a diktat.

Hungarian government officials also hoped in the days following the Munich Agreement that the declaration of Slovak autonomy could bind the whole of Slovakia to Hungary. With respect to Transcarpathia, the recovery of the entire territory, based on ethnic and historical principles, was never kept secret as a goal of Hungarian revision, whether conceived in terms of a complete and immediate merger or as a sequence of gradual resolutions. In the case of Transcarpathia, which had a 55% Rusyn majority in 1910, not only was there the stated strategic, and even more emotional, goal of having a common Polish-Hungarian border, Hungarian governments also hoped that the plan for Transcarpathian autonomy would present an attractive alternative to an agreement with historical nationalities. In 1938, however, ethnic revision had become the main configuration of Hungarian demands, i.e., the acquisition of those Slovak and Transcarpathian territories with a Hungarian-majority population according the 1910 census. However, this Hungarian course of action, which found a legal basis in the Munich Agreement, was deemed unacceptable to both the Czechoslovak and autonomous Slovak governments.

The 1910 census disclosed a very strong assimilation gain in favor of the Hungarians, a gain nevertheless exaggerated by all contemporary and subsequent analyses. In addition to the pronounced growth in, and relative majority of, the Hungarian population in towns such as Pozsony (Bratislava), Nyitra (Nitra), Besztercebánya (Banská Bystrica), and Zólyom (Zvolen), the 1910 survey also recorded a significant degree of Magyarization in the bilingual, dual-identity ethnic contact zones. No Czechoslovak government, however, could have agreed to hand over Nitra, Košice (Kassa), and especially Bratislava – let alone all three together. These ethnic disagreements made the bilateral talks, which had begun in Komárno (Komárom) on October 9, 1938, hopeless from the start.

An additional consideration was that both national governments, as well as the autonomous Slovak government, hoped that by demonstrating the failure of the bilateral talks, they could establish a more advantageous negotiating position before an arbitration panel composed of the great powers than if the other side had made maximum expected concessions. Moreover, the Hungarian formulation of revisionist doctrine considered the participation of the great powers – Britain, France, Italy, and Germany – in securing a decision as more important than achieving an alternative bilateral compromise with the Czechoslovak government.

At the same time, it is known that Germany was intervening behind the scenes before the Komárno talks and then openly afterward. In doing so, it intruded into the conflict between the two countries by supporting Tiso’s formulation of the Slovak position on most of the controversial issues (including Bratislava, Nitra, and Košice). In the end, it was the Italian government, however, in the persons of Mussolini and Count Ciano, whose intervention in the issues of most importance from the Hungarian perspective altered the course of events, which neither Prague nor Bratislava realized for some time. Within Hungary itself, meanwhile, the conflict between the options of the restoration of lost territory and an ethnic-based revision was experienced by all the leading politicians of the day. Even Pál Teleki, who was considered the most committed supporter of a complete restoration, was forced to acknowledge European nation-state realities, including those of Central Europe, and accept the alternative of ethnic-based border changes.

Hitler’s temporary retreat

Throughout the spring and summer of 1938 it appeared as if Hitler might opt for Case Green (Fall Grün) and the military invasion of Czechoslovakia, but a number of factors, including Berlin’s concerns over British-French negotiations, the strength of the Czechoslovak army and defensive positions, the risk of Soviet military intervention, and Hungary’s spurning the intended role of initiator of the intended war, led to temporary German satisfaction with the annexation of Sudeten-German majority territory. The failure of the Runciman Mission, which was tasked with investigating the German question in Czechoslovakia and the issue of a minority settlement as well as performing the role of a mediator of sorts, demonstrated that Prague’s Western allies – on the pretext of “preserving the peace” – would not be coming to Czechoslovakia’s defense.

At the same time, it had already become clear by August 1938, during the high-level German-Hungarian discussions held in Kiel, that the Germans had begun to view the war-adverse Hungary as a less and less suitable partner for a military confrontation with Czechoslovakia. In fact, the German foreign ministry had already warned the Führer even before the Kiel talks that a precipitate attack by Hungary against Czechoslovakia could provoke action on the part of the other Little Entente partners, Romania and Yugoslavia. “Hungarian assistance would be of no benefit to us if it simply gains us new adversaries,” read a memorandum from August 22, 1938.

Berlin also had to face the fact that Hungary was not only militarily unprepared for an armed attack upon Czechoslovakia – either preceding a German attack or launched simultaneously with the latter – but also that its idea of a complete restoration of lost historical territory was unrealistic. Taking into account resistance on the part of the Slovaks themselves, lacking any prior agreement with the other Little Entente states, and considering Poland’s increasingly pro-Slovak sentiments, the Imrédy government simply could not entertain the notion of restoring the former Upper Hungarian territories in their entirety. Taking Trianon-Hungary’s international position into account, an ethnically-based revision – Transcarpathia excepted – became the primary objective in formulating Hungary’s territorial claims against its neighbors.

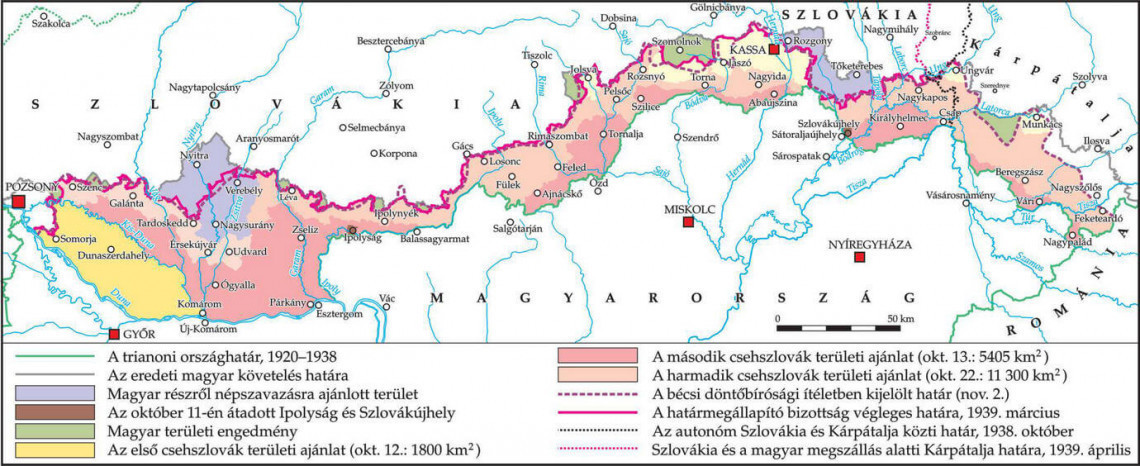

On November 2, 1938, Italian Foreign Minister Count Ciano and his German counterpart Ribbentrop signed the first Vienna Award, which amended Hungary’s border with Czechoslovakia, at the Belvedere Palace in Vienna. The award, an ethnic-based revision, returned 11,927 km² of territory and 896 thousand inhabitants to Hungary, of whom 86% – roughly 750 thousand people – were of Hungarian nationality.

It is a commonplace of diplomatic history that, faced with Hitler’s aggressive territorial designs, Britain and France were of the temporary opinion that the pursuit of appeasement could restrain and placate a saber-rattling Germany. However, the actual guiding principle of the two Western powers’ Central European policy remained countering the conflict-increasing effects of the Rome-Berlin axis and mitigating the flashpoints of war while opposing any further border changes.

At the same time, in the context of Czechoslovakia’s foreign policy isolation, developments in the country’s internal politics and minority policies were closely linked to Germany’s increasingly aggressive actions. The escalation and intensification of the Sudeten-German, Slovak, Polish, Rusyn, and Hungarian issues were a consequence of Hitler’s openly interventionist foreign policy, which became more aggressive in the wake of the Anschluss. However, even in the absence of Hitler’s interventionist policy, the unsettled constitutional status of the almost fifty percent non-Czech inhabitants of the country would have awaited resolution.

Prime Minister Milan Hodža’s efforts in connection with the minorities statute proved insufficient in providing a clear pathway for resolving the increasingly threatening constitutional crisis occasioned by the Slovak, Sudeten-German, Rusyn, Hungarian, and Polish issues. All these external and internal developments also prompted the involvement of Czechoslovakia’s two other concerned neighbors – Poland and Hungary – and in the weeks following the Munich Agreement it became clear that neither of the bilateral agreements specified in the supplementary declaration were attainable.

On the eve of the Munich Four-Power Conference, it was especially important for Hungary to obtain the benevolent attention of the host, Germany, and allied Italy while also maintaining the goodwill of both Britain and France to ensure that a decision be taken in respect to the Hungarian issue at the same time as the Sudeten-German question. The Hungarian Foreign Ministry continuously instructed its ambassadors in Berlin, Rome, and London to bring to the attention of official circles that “should there be any discrimination at Hungary’s expense in the resolution of the Czechoslovak business, then the Hungarian government is prepared to do anything.”

Germany and the Hungarian-Czechoslovak territorial dispute

As noted, the supplementary declaration to Munich Agreement required the issue of the Polish and Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia to be resolved. This elevated Hungary’s revisionist demands from vague diplomatic talks to a bilateral solution with the Czechoslovak government within a period of three months – in the absence of which a binding four-power decision would be imposed. Nevertheless, using the Munich arrangement as a model and principle for the return of Hungarian-majority settlements based on the last census data prior to 1918 presented a host of difficulties. First and foremost, the bilateral talks had to take into consideration ethnic relations that had undergone numerous radical changes between 1918 and 1938.

One particular difficulty with the 1910 Hungarian census was the often ambiguous data specifically concerning the towns and counties of Upper Hungary which could only be explained by recourse to statistical arguments, such as the relative Hungarian majority in Besztercebánya (Banská Bystrica) and Zólyom (Zvolen), the 30% Hungarian share in Trencsén (Trenčín), and the nearly 80% Hungarian share in Kassa (Košice). Moreover, there were the added complexities of the widespread dissimilation processes among the Jewish population and the frequent instances of dual and triple identity among the urban population.

The steady decline in the alternative of a complete and thoroughgoing revision occurred in tandem with Germany’s strengthening position in Central Europe primarily because the German leadership regarded support for the maximum revisionist goals of a militarily and economically weak Hungary as out of the question. Theoretically, there might have been some chance for this in the case of Slovakia and Transcarpathia, but in 1938, even the Hungarian political and military leadership considered this feasible only in connection with Transcarpathia.

Ethnic revision applied exclusively to Slovakia after the Hungarian government declined the role of instigator or expendable pawn offered by Hitler in a military attack on Czechoslovakia. The Hungarian government had several reasons for this, the most important being the threat of attack from the other two Little Entente states and the lack of preparedness on the part of the Hungarian army. Moreover, in pursuing ethnically-based territorial changes, the Hungarian government could count on the support of all the major European powers and even the limited support of Czechoslovakia from August 1938 onwards.

This was undoubtedly a particularly important aspect of the Hungarian revisionist doctrine developed by Bethlen and Teleki – akin to an avoidance of war – since Hungarian diplomacy always regarded the durability of border changes as dependent upon some sort of European consensus and the joint support of the great powers. However, this became increasingly unlikely as Hitler’s Germany became increasingly dominant in Central Europe.

The Komárno talks

Negotiations between the Hungarian delegation led by Foreign Minister Kánya Kálmán and the Czechoslovak government delegation led by Slovak Prime Minister Jozef Tiso began on October 9, 1938, at 7 pm in the county hall in the Slovak half of Komárno (Komárom). Based on the supplementary declaration to the Munich Agreement, the parties were given three months to resolve the border issues between the two countries. The parties adopted French as the official language but agreed to negotiate in Hungarian.

At the end of the first round of talks, Kálmán Kánya presented a document in French which proposed a referendum for all nationalities, including the Slovaks and Ruthenians, in the former Hungarian territories. Naturally, however, the Hungarian side was “primarily interested in the fate of those areas inhabited by a Hungarian majority.” Applying the principle decided upon in the Munich Agreement, which saw the transfer of the Sudeten-German territories, he demanded the immediate return of those Slovak and Transcarpathian territories that had a Hungarian majority according to the 1910 census. The initial Hungarian claims included towns and villages located on the periphery of the Hungarian-speaking area, including Devín (Dévény), Bratislava (Pozsony), Nitra (Nyitra), Jelšava (Jolsva), Košice (Kassa), Mukačevo (Munkács), and Užhorod (Ungvár).

The Czechoslovak side consistently rejected these Hungarian demands throughout the five days of talks, which lasted until October 13. Instead, they first proposed autonomy for the Hungarian territories, then to hand over the Csallóköz region, and finally, in their third proposal, they aimed at the creation of two equal blocs of minorities on both sides of a renegotiated border while maintaining Slovak control over the railway lines. This was rejected by Pál Teleki and Kálmán Kánya, who threatened to break off negotiations. Meanwhile, the Slovakian side completely ruled out surrendering Bratislava, which the Hungarian delegation tacitly acknowledged. The Slovaks steadfastly refused to surrender other cities in Hungarian-speaking territory as well, such as Košice, Užhorod, and Mukačevo. One of the main reasons for the failure of the talks concerned the latter three cities, which proved to be an intractable issue during the bilateral negotiations.

During the five days of plenary sessions and expert discussions, Pál Teleki, the Imrédy government’s minister of religion and public education and an outstanding expert on minority issues and geography, rejected Slovak objections to the Hungarian census data along with Tiso’s proposal that the issue of minorities within the two countries be resolved through population transfers.

When the Czechoslovak delegation declined to make a proposal more in line with Hungarian demands based on Munich principles, Kánya Kálmán informed the meeting that began at 7 pm on October 13 that “the gap between the positions of the two delegations regarding the principle of reorganization is so great that it cannot be hoped to be overcome at these talks.” With this statement, the Hungarian side considered the Komárno talks as concluded. At midnight on the same day, Prime Minister Imrédy convened an extraordinary meeting of the Council of Ministers where a decision was taken on the military draft of the 1908-1911 age group. The meeting also saw the dispatch of Kálmán Darányi and István Csáky to Germany and Italy, respectively, to inform Hitler and Mussolini of the developing situation.

The return of Sátoralja-(Szlovák)újhely and Ipolyság

As a precondition for the Komárno talks, the Hungarian government requested amnesty for Hungarian political prisoners in Czechoslovakia, the discharge of Hungarian soldiers serving in the Czechoslovak army, and the establishment of Hungarian police units in the Hungarian territories concerned, in addition to the Czechoslovak government handing over two border settlements. During the talks on the evening of October 9, the military experts of the two sides, Hungarian Colonel-General Rudolf Andorka and his Czechoslovak counterpart General Rudolf Viest, agreed that Czechoslovakia would hand over the village of Slovenské Nové Mesto (Szlovákújhely), a former suburb of the Hungarian town of Sátoraljaújhely, within 24 hours, and the town of Šahy (Ipolyság) within 36 hours. On October 11, 1938, the 1st Budapest Honvéd Infantry Regiment marched into Ipolyság and were the first to introduce the Hungarian pengő, which was worth seven Czechoslovak koruna. Hungarian radio provided a live broadcast of the euphoric celebrations as the first Hungarian town returned home.

Berlin distances itself from Budapest

Hitler’s famous utterance, expressed in Kiel, that whoever “wishes to dine with the Germans must also help cook,” essentially defined Hungary’s political and military role. Although the Imrédy government tried its best to comply with this, it still managed to steer clear of military intervention during the most intense phase of the Czechoslovak crisis.

The reports submitted by the Hungarian ambassador in Berlin, Döme Sztójay, in September clearly reflected growing German pressure. On September 10, German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop warned Hungary against any hasty ultimatum directed against Prague. Six days later, Field Marshal Göring subjected Sztójay to a mild rebuke, noting that “he hasn’t seen anything in either the world press or the Hungarian press or in the statements of the Hungarian party or Hungarians in Slovakia that would draw the world’s attention to the idea that the Hungarians in Slovakia should be reunited with the motherland by ‘right of blood.’”

The next day, Göring sent word through Sztójay about what should be done. He suggested that Hungary “officially demand the right of self-determination for the Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia in the most forceful and vigorous manner.” Moreover, he proposed that “the Hungarian minorities proceed in the same fashion as Henlein’s [leader of the Sudeten Germans] appeal to the Czechoslovak government and all relevant governments” and that “they should provoke armed clashes, strikes, and disobey call-up orders, because only forceful measures will draw the attention of the Western powers to Hungarian demands.” Göring also wanted to persuade the Warsaw and Budapest governments to influence the Slovaks “in adopting a similar attitude and to demand self-determination.” Lastly, he warmly advised that the Hungarian ambassadors in London and Paris “should knock on the doors of government there as much as possible, just as the Czechoslovak ambassadors do, several times a day,” and that the Hungarian government should do everything possible to ensure that the foreign press devote more coverage to the Hungarian issue. Göring tried to instil the fear that Hungarian passivity and inaction would lead the Western powers to only want to settle the issue of the Sudeten Germans and forget about the Hungarians.

Munich and Berlin as the scene of discussions

In the days following the Munich Agreement there was a brief moment when the Hungarian side believed there was possibility that the Czechoslovak government crisis and subsequent proclamation of Slovak autonomy in Žilina (Zsolna) on October 6 could bring the whole of Slovakia to Hungary. This is why the decisive action undertaken by the Tiso-led Slovak autonomous government in firmly rejecting a common-state solution was acknowledged with visible resignation on the part of the Hungarian government at the negotiations session of October 7, 1938, intended to discuss the consequences of Slovak autonomy.

Following the failure of the Komárno talks, the German and Italian governments tried to act as mediators in resolving the disputed issues. First, Ribbentrop and Hitler received the Czechoslovak delegation led by Jozef Tiso, and then on October 14, they held talks with the Czechoslovak Foreign Minister František Chvalkovský and the former Hungarian Prime Minister Kálmán Darányi. Of particular concern was the increasing pressure from the German government, which both sides experienced after the failed talks in Komárno.

Zsigmond Fülöp, bank director and city judge of Komárom, formerly Slovak Komárno, greeting Regent Miklós Horthy and his wife, Prime Minister Béla Imrédy, Minister of Religion and Education Pál Teleki – in scout uniform, State Secretary Ferenc Zsindely, and the mayor of Újkomárom Gáspár Alapy, at the main square in formerly Slovak Komárno, November 6, 1938.

During the negotiations in Berlin and Munich, Darányi was confronted with the fact that the Hungarian border proposal had either been misinterpreted by Reich Foreign Minister Ribbentrop or been deliberately modified to offer the Slovaks a favourable negotiating position. The resultant Ribbentrop Line, construed by leaving out Košice, Mukačevo, and Uzhhorod, was presented to the Czechoslovak Foreign Minister Chvalkovský and the Slovak-Ruthenian delegation of Tiso and Edmund Bachinsky as a German solution already agreed upon with the Hungarians. Darányi protested against this in a letter on October 23, insisting that Košice and the two Transcarpathian cities come under Hungarian rule. As for the other communities disputed by the Slovaks – Nitra, Jelšava, and Smolník and its surroundings – he still considered a referendum the best solution. In his reply, Ribbentrop acknowledged the Hungarian claim to Košice but supported the Czechoslovak position with respect to Uzhhorod and Mukačevo. This position would change during the negotiations between Ciano and Ribbentrop, and between Hitler and Mussolini.

According to a German memo of the meeting between Darányi and Hitler, Hitler – recognizing Germany’s inherent interests in an autonomous Slovak – rejected the Hungarian referendum efforts, stating that the Slovaks and Ruthenes no longer wished to automatically return to the Hungarian state. “A referendum cannot be forced upon the Slovaks. They naturally want to be independent and definitely do not want to unite with Hungary.”

The Führer identified the weakness of Hungary’s negotiating position in its military indecision and, criticizing Darányi for having missed the most opportune moments from the Hungarian perspective, noted: “If war had happened, Hungary could have had all of Slovakia, but now it has to adapt to what is possible.” In reference to this, Darányi was also asked during the talks held in Munich whether he would be interested in occupying part of Slovakia while subjecting the rest to a referendum. The former prime minister considered only the occupation of the Hungarian-populated territories as feasible, referring to the expected hostile attitude of Romania and Yugoslavia. Hitler summed up this part of the conversation as follows: “In any case, the decisive factor is not who is right, but who has power.” Hitler concluded by proposing, almost in the form of an ultimatum, that the Hungarian government withdraw from the League of Nations, join the Anti-Comintern Pact, and dismiss Foreign Minister Kánya.

The day before Darányi’s visit, Jozef Tiso, the prime minister of the Slovak autonomous government, also met with Hitler on behalf of the Czechoslovak government. In the course of this meeting, Tiso was apparently able to convince the German leader that Bratislava, Košice, and Uzhhorod were also of fundamental importance for the second Czechoslovak Republic. The resultant German promises were reflected in the third Czechoslovak territorial proposal which forced the Hungarian government to file a protest in Berlin. This German commitment caused a complication in the latter half of October, one which was eventually resolved with the help of the Italians and ended with Košice, Uzhhorod, and Mukačevo being transferred to Hungary.

On January 16, 1939, Hitler reviewed the Hungarian-German situation that had developed following the Vienna decision with the new Hungarian Foreign Minister István Csáky, who had replaced Kánya. Hitler indignantly rejected former Prime Minister Bethlen’s criticism who in the 1939 New Year’s issue of Pesti Hirlap [Pest News] blamed Germany for the revision of the Upper Hungarian border having been limited to Hungarian-ethnic areas. Instead, Hitler – otherwise in line with the facts – blamed Hungary’s dithering, its positioning on ethnic grounds, and both Kánya’s Bled Agreement and Darányi’s Munich negotiations, as well as the Hungarians expectation that Germany should pull Hungary’s chestnuts out of the fire for them. He described as “idiotic” those statements criticizing the Germans’ negative attitude toward a Polish-Hungarian border. He could contrast the situation with the Greater German Reich compared to that of the Kingdom of St. Stephen: in failing to attack Czechoslovakia, Hungary had missed the opportunity for a complete restoration of its lands, opting for an ethnic revision instead, and there was no possibility of going back.

Contemporary assessments of the Vienna decision

Five days after the first Vienna decision, on November 7, 1938, the Hungarian Historical Society organized a celebratory gathering in Budapest. As the main speaker of the event, the society’s president, Bálint Hóman, sought, among other things, to explain why the German and Italian foreign ministers, who played the role of arbitrators, established the new Hungarian-Czechoslovak border on the principle of nationality, in the “spirit of popular thought,” rather than on the basis of “absolute historical justice.” All contemporaries were aware that Germany played a decisive role in the great power deliberations regarding the border adjustment. However, only a handful of the Hungarian governing elite could know how and why German diplomacy modified the Case Green plan, which set the goal of liquidating Czechoslovakia by October 1, 1938, and what roles and tasks it assigned to Hungary and what territories were promised it.

Naturally, Hóman also emphasized to what extent this first success of Hungarian revisionist policy was attributable to Hitler, and thus, the society’s celebratory gathering sent a telegram of thanks to the Führer. A report about the event by the German ambassador in Budapest highlighted that Hóman considered the German national idea to be an important guiding principle and stated that the realization of the cultural and political unity of the German people spoke of Hitler’s undoubted relevance to Hungary. He stressed that Berlin “stood by Hungary’s side with German loyalty” and together with the Reich foreign minister facilitated the return of one million Upper Hungarian brothers to the motherland. According to the report compiled by the German ambassador in Budapest, Otto Erdmannsdorf, on November 9, at the end of his speech, Bálint Hóman nevertheless expressed the conviction that “the national principle must be merged with the historical principle, that is, the Carpathian border must be claimed in Hungary’s favor.”

Most of the Hungarian political press and public opinion of the day reacted in a similar way to the events at the Belvedere Palace. The only discernible differences were that among the leading Hungarian politicians, some regarded Italy, that is, Mussolini and Foreign Minister Ciano, as more consistently pro-Hungarian than the Germans. They included István Bethlen, Pál Teleki, and János Esterházy, who departed for Rome the day before the decision to provide Hungarian background information requested by Ciano prior to the Vienna decision.

During the march into Komárom, formerly Slovak Komárno, the regent was greeted with a bouquet of flowers by three girls – Éva Kállay, Sári Kecskés, and Gizike Gögh – dressed in traditional Hungarian dress. Hungarian soldiers were greeted with similar enthusiasm and gratitude in every town and village.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)