On January 16, 1920, Count Albert Apponyi, head of the Hungarian delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, gave a speech in which he launched a general attack on the proposed peace terms. He recognized the right of the victors to “impose the consequences of the war on those responsible” but criticized the severity of the peace terms, especially the territorial provisions, which seriously violated the principle of nationality. He then tried to prove, using geographical, strategic, economic, and cultural arguments, that maintaining historical Hungary would be a better solution for the peoples concerned and for Europe as a whole than dismemberment.

A unified state, he explained, would have better defense capabilities and would also represent a stable barrier against the expansion of despotic empires and ideas from the East. Moreover, it would also enable exemplary economic cooperation in the areas of labor flows, transportation, commodity exchange, and money circulation. Dismemberment, however, would create small, squabbling states, some of which would have insufficient experience in governance.

Apponyi, therefore, proposed that the principle of national self-determination, proclaimed by Wilson and accepted as the basis of a peace settlement, be followed in the matter of borders and that plebiscites be held in the areas intended for annexation.

Apponyi delivered his speech in French and repeated it in English, slightly abridged in sections, for the benefit of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who did not speak French well. At the end of his roughly seventy-minute speech, Apponyi directed a few remarks to the Italian Prime Minister Francesco Nitti, expressing his hope that the Italian-Hungarian friendship that existed before the war would be restored as soon as possible.

Apponyi’s speech was recorded by both Hungarian and foreign stenographers present, so it has survived in several versions with minor differences.

Unacceptable peace terms

“[…] I feel the enormous weight of responsibility that has befallen me at this moment to be the first to speak on behalf of Hungary as regards these terms. I state without hesitation, however, that the peace terms, as you have provided them to us, appear unacceptable to us without substantial modifications. I clearly see those dangers and troubles that could arise from a refusal to sign the peace. Yet, were Hungary to be put in the position of having to choose between accepting this peace or refusing to sign, she would actually have to ask herself whether to favor suicide in order to escape death.

Fortunately, it has not come to this yet. You have called upon us to make our observations and we have taken the liberty to present some of these even before receipt of the peace terms. We are confident that you will study those of our comments already submitted and those to be submitted hereafter with the requisite seriousness and conscientiousness demanded by the gravity of the situation. We thereby hope to convince you. We hope this all the more as it is not our intention, neither today nor later, to give vent to our emotions or to represent the exclusive standpoint of those interests we are tasked to defend. We are seeking a common position that allows for mutual understanding. And, gentlemen, we have already found this position in the principles of international justice and the freedom of peoples, which the Allied Powers have proclaimed so highly, and in the great common interests of peace, stability, and European reconstruction.

It is from the perspective of these principles and interests that we will examine the peace terms offered to us. Above all, we cannot conceal our astonishment at the extreme severity of the peace terms. […]

For Hungary, this would mean losing two-thirds of her territory and almost two-thirds of her population, and what would remain of Hungary would be deprived of almost all the requisites for economic development. For this unfortunate central part of the country, cut off from its periphery, would be deprived of most of its coal, ore, and largest portion of its salt mines; its timber, oil, and natural gas sources; a good part of its work force; and the alpine pastures that fed its cattle. This unfortunate central part, as I have said, would be deprived of all the sources and means of economic development at that moment when they are expected to produce more. Considering such a difficult and extraordinary situation, the question arises as to which aspect of the above-mentioned principles and interests has occasioned this especial severity towards Hungary.

Could this be meant as a judgment passed against Hungary?

You, gentlemen, whom victory has placed in the judgment seat, have declared the guilt of your former enemies, the Central Powers, and have decided to impose the consequences of the war on those responsible. So be it! But in this case, I believe that retribution should be proportional to the measure of guilt, and since Hungary is subject to the most severe conditions, threatening her very existence, one might believe that Hungary is the most culpable of nations. Gentlemen! Without delving into the details of this question – for we shall submit documents for this purpose – I believe, first of all, that such a judgment cannot be pronounced on a nation that, at the very moment when the war broke out, did not enjoy complete independence and could only exercise partial influence over the affairs of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and which nation, as proved by documents that have recently come to light, nevertheless used such influence to oppose those steps that were to lead to war.

I also do not believe that we are dealing with a judgment, for a judgment presupposes a procedure in which the parties are heard under equal circumstances and given an equal opportunity to present their arguments. Hungary, however, has yet to be granted a hearing; thus, it is impossible that the peace terms should have the character of a judgment.

Or perhaps it is a question of applying the principle of international justice with the intention of replacing polyglot state formations, of which Hungary is one, with new states as a means of resolving the territorial issues between different nationalities in a more equitable manner and more effectively ensuring their freedom. On reviewing the facts, however, I am forced to doubt that this is the motive behind these solutions.

First of all, 35% of the 11,000,000 souls to be torn from Hungary are Hungarian, which means three and a half million, even if we take the most unfavorable calculation for us as a basis. This number also includes around one and a quarter million Germans, which, together with the percentage of Hungarians, comprises 45% of the total. For them, this application of the nationality principle would not present an advantage but rather a train of suffering. Even if we presume – which I am far from doing – that the application of the nationality principle would create a more advantageous situation for the remaining 55% of historical Hungary, this principle cannot be said to apply to the almost half of the population to be cast off, or if it does apply, it must do so in a contrary sense.

However, I believe that when it comes to principles, they should be applied equally to all those affected by the provisions of the treaty.

But let us go further and consider the states that have arisen on the ruins of Hungary. We can conclude that from a nationality perspective, these will be just as or perhaps even more divided than the former Hungary. […]

I do not see how the principle of nationality, the principle of national homogeneity, would benefit from this dismemberment. Only one consequence would follow from this, which I dare mention without intending offense to anyone. I simply wish to point out the fact that the consequence of this would be the transfer of national hegemony to nationalities that, for the most part, are presently on a lower level of culture.”

A single day was given

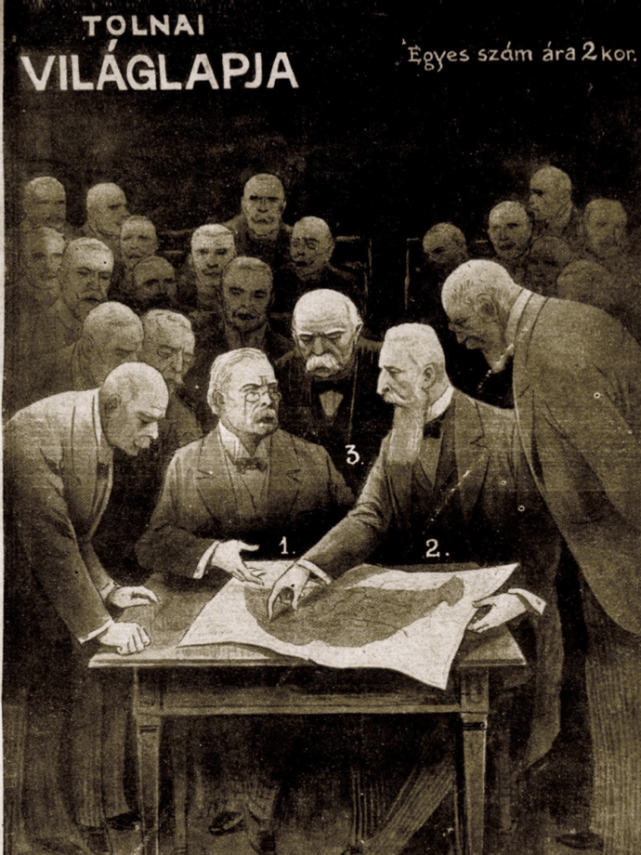

The Hungarian delegation received the preliminary peace terms at the French Foreign Ministry on January 15, 1920, and Albert Apponyi, the head of the delegation, was allowed to present his comments to the representatives of the victorious powers the following afternoon.

Apponyi, therefore, had less than a day – including the nighttime hours – to compose his speech. The members of the Hungarian delegation, therefore, divided the voluminous text of the peace terms, which exceeded a hundred pages, into subject groups so that the delegation’s experts and politicians could read through it as quickly as possible and provide expert commentary on its points. Their notes and suggestions were then passed on to Apponyi, who first began to dictate his speech for the following day based on these, but ultimately decided to simply make notes and summarize what he had to say in a free speech in accordance with “parliamentary traditions.”

Hungarian “cultural superiority”

“I will cite a few figures to prove the truth of what I say. The number of Hungarians who can read and write is almost 80%, while among German-speaking Hungarians the figure is 82 %, for Romanian speakers 33 %, and for Serbian speakers 59 and a few decimal points, almost 60 %.

If we consider the higher social classes and take into account those who have completed high school and passed the exam called the baccalauréat in France, we can conclude that the number of Hungarians among those who have completed such studies and have achieved an equivalent to a high school diploma is 84 %, despite Hungarians constituting only 54.5 % of the population. The number of Romanians among those who have completed such studies is 4 %, even though they constitute 16 % of the total population, while the number of Serbs is 1 %, although they comprise 2.5 % of the total population.

I repeat, I do not intend to cause anyone offense with my remarks. The sole reason for this situation is that these neighboring peoples, due to unfortunate historical circumstances, entered the family of civilized nations later than we did. This fact is undeniable. I would think, thereby, that the transfer of national hegemony to a lower cultural level would not be a matter of indifference to the great cultural interests of humanity. We have evidence of this already. Our neighbors, desiring parts of our territory, have already taken them under their power for at least a year now. According to the armistice agreement, they had the right to militarily occupy these territories, yet they have usurped the entire machinery of government. The consequences of this are already visible. In separate documents we will show how many great cultural values have been destroyed in just this one year. You will see from these documents, gentlemen, how two of our universities, which stand at the highest levels of culture, the University of Kolozsvar, an old seat of Hungarian culture, and the more recent University of Pozsony, have been ruined. The teachers have been dismissed, and I would like you to inquire as to who were put in their place. I call on you to send out standing committees of scholars and scientists to ascertain the state of affairs so as to be able to make comparisons. It is impossible that these universities and these faculties, whose history stretches back into the distant past, should disappear like this and be replaced by anyone. Such great cultural edifices cannot be replaced by upstarts and parvenus.

The situation is similar for the entire administrative machinery and at all levels of the teaching staff. […]”

A plebiscite!

“We have already seen that severity imposed upon Hungary cannot result from a judgment. And we have seen that the nationality principle would gain nothing from this either. Could it be that we are faced with an intention that follows from the idea of the freedom of peoples?

It would seem the starting point of this intention would be the supposition that the non-Hungarian inhabitants of Hungary would prefer living in a state in which the constituent element would comprise their ethnic kindred rather than in a Hungary where Hungarian hegemony prevails.

However, this is merely a supposition, and if we are going to pursue the path of suppositions, dare I say this supposition could also be applied in a contrary sense to the 45% of Hungarians and Germans who will now be attached to new states and about whom it could just as rightly be supposed would prefer to remain members of the Hungarian state. This line of reasoning would mean nothing more than placing the advantages on the other side. But why should we proceed from conjectures and suppositions when we have a simple and unique tool at our disposal for ascertaining the truth, a tool whose application we loudly demand in order to clarify this issue? This tool is the plebiscite.

In demanding this, we refer to that great ideal so eloquently expressed by President Wilson, namely, that no group of people and no population may be transferred from the jurisdiction of one state to another without its consent and without consultation, as if a herd of cattle. It is in the name of this great ideal, this axiom of good sense and public morals, that we demand a plebiscite in those parts of our country that they now wish to tear away from us. I declare in advance that we will bow to the results of such a plebiscite, whatever they may be. Naturally, we also demand that such a plebiscite be held under conditions that will ensure its freedom.

Such a plebiscite is all the more necessary as the National Assembly, to which belongs the ultimate responsibility for deciding on the proposed peace terms, will be truncated. The inhabitants of the occupied territories will not be represented here. And no government or national assembly has the legal or moral authority to decide the fate of those who are not represented therein. […]

I have no wish, on this occasion, to plead the case intended to be filed against Hungary for the alleged oppression of non-Hungarian races. I can only tell you that we would be well pleased if our Hungarian brethren in the territories torn away from us were to enjoy the same rights and advantages that the non-Hungarian citizens of Hungary enjoyed. […]"

In praise of historic Hungary

"We will present, gentlemen, an entire series of documents, especially concerning events that have taken place in Transylvania. We have rigorously examined all the reports that have been received in this regard, and although their veracity is confirmed by the leading men of the three Christian churches in Transylvania – the Roman Catholic, the Calvinist, and the Unitarian – we do not expect – we cannot expect – that credence be given to our mere assertions, as declarations can be countered by other declarations. We ask of you, however, to investigate what has happened there on the ground and to send a committee of experts to the scene before making a final decision so that they can verify what is happening in the aforesaid territory.

We alone, gentlemen, demand that the obscurity surrounding the situation be dispelled; we alone seek decisions that stem from full knowledge regarding the issue. We also ask that, in the event that territorial changes are ultimately forced upon us, the rights of national minorities be afforded more effective and more detailed protection than those envisaged in the peace proposal submitted to us. We firmly believe that the assurances provided for are completely inadequate. We require more powerful assurances, which we are fully prepared to apply in respect to the non-Hungarian population remaining in Hungary. […]

Gentlemen! The Hungarian problem is not such an insignificant part of the general problem as the raw numbers of statistics would suggest.

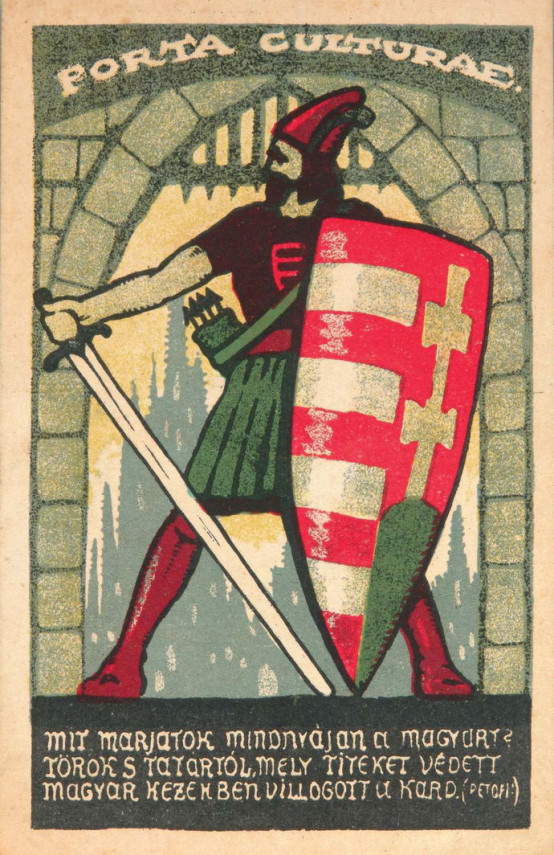

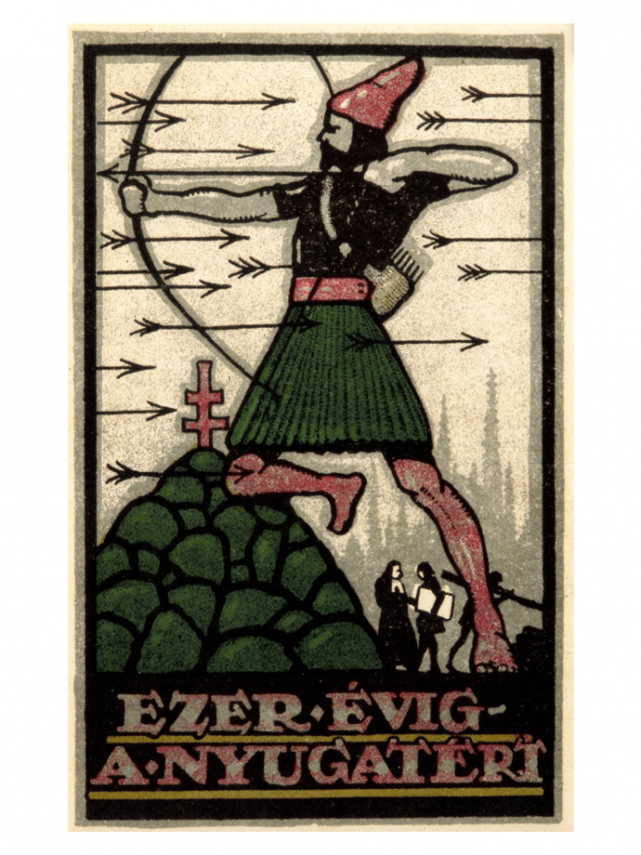

This territory, which makes up Hungary and which is legally still Hungary even today, has for centuries played an extremely important role in maintaining peace and security in Europe, especially in Central Europe. For centuries before the Hungarian conquest and the Hungarian conversion to Christianity, unrest and insecurity reigned in this part of the world. Central Europe was a battleground for all manner of barbarian peoples. Security was ensured only after the Hungarians established a defensive barrier. For the sake of peace and stability, it is of the utmost importance that the main hotbed of unrest in Eastern Europe not gain ground and spread to the heart of Europe. Historical development was impeded in the Balkans due to the Turkish occupation, and such balance is yet to be restored. Heaven grant that this happen before too long. But it is of signal importance today that those disturbances that have so often upset the peace of Europe and so often brought us to the brink of war not be allowed to spread further.

Historical Hungary fulfilled this task of maintaining a state of balance and stability, thus ensuring Europe’s peace against the immediate dangers threatening from the East. And she performed this vocation for ten centuries, her organic unity alone qualifying her for this task. I quote here the words of the great French geographer, Élisée Reclus, who declared that this country possessed such a perfect geographical unity as to have no rival in Europe: ‘Her system of rivers and valleys, which, starting from the borders and striving for the center, forms a unity that can be governed only by a single power. The economic interdependence of her parts is also perfect, since the center forms a vast agricultural enterprise while the periphery contains everything necessary for the development of agriculture.’

Historical Hungary, thus, has a natural geographic and economic unity that is unique in Europe. No natural boundaries can be drawn within its territories, and no part can be torn away without causing suffering to the rest. This is why history has preserved this unity across a span of ten centuries. You may reject the words of history in fashioning a legal construct, but historical evidence compiled over a thousand years cannot be ignored. This is not accidental; it is simply the nature of things. Hungary possesses all the conditions for organic unity, except one – racial unity. And yet, as I have already stated, those states to be built on Hungary’s ruins under the peace treaty would also lack racial unity – the only unity Hungary lacks – while being bereft of all the others. The new states to be formed would cut across natural geographical boundaries and impede beneficial internal migration, impelling workers towards more favorable employment opportunities; they would break the threads of tradition binding those who have lived together for centuries in a common mentality, those who have experienced the same events, the same glory, the same progress, and the same sufferings. Is our fear, then, not justified that instead of this well-tried and true pillar of stability, new sources of unrest will come to the fore? For we must not delude ourselves – these new state formations will be undermined by irredentism of a much more dangerous form than some have perceived in Hungary. Although such a movement, if it did indeed exist among some portion of the more educated classes in Hungary, nevertheless never penetrated into the great masses of the people.

These new states, however, would be undermined by the irredentism of peoples feeling not only the rule of an alien power but also the hegemony of those possessing a culture inferior to their own. And here we must put forward an organic impossibility: whereas we can conceive the possibility of a national minority of a higher cultural level exercising hegemony over a majority at a lower level, to posit a minority possessed of a lower cultural development or a very small majority of the same exercising hegemony over a national community of a higher cultural level yet expecting voluntary subordination and moral assimilation is, gentlemen, an organic impossibility."

The survival of historical Hungary in the European interest

"We are often accused of seeking to forcibly subvert any settlement of the issues that runs counter to our liking. Such foolish plans are far from us, gentlemen. We place our hopes in justice instead and in the moral strength of those principles on which we rely, and what we cannot achieve today we expect to be achieved through the peaceful action of the League of Nations, one of whose tasks will be to remedy those international situations that could threaten the preservation of peace.

I declare this lest my words be seen as childish and futile threats. But I also declare, gentlemen, that with such artificial provisions as are contained in the peace treaty, it will not be possible to create a peaceful political situation in this much-suffering part of Europe, so important from the perspective of a general peace. Only the stability of the historical Hungarian territory can safeguard Central Europe from the dangers issuing from the East.

Europe is in need of economic reconstruction, but such development will certainly be hindered by the new state formations. This will certainly be the case in what remains of Hungary, but the situation will be similar in those parts torn away. The same will happen in the separated territories for the simple reason that they will be subject to a lower standard of administration corresponding to a lower level of culture. Moreover, they will be separated from the other parts of an organic unity with which they could flourish once more, but without which they are doomed to stagnation or possible decline.

Europe is in need of social peace, but you yourself know better than I what dangers threaten this peace. You yourself know better than I how the consequences of the war have disrupted and thrown off balance the culture and conditions of economic life. We know from past sad experience that the successes of subversive elements are entirely the result of factors that undermine the moral strength of society, that is, everything that weakens national sentiment, but above all, the suffering caused by unemployment. If in this part of Europe, which is in close proximity to the still-burning embers of Bolshevism, the conditions of labor are made more difficult and the ability to resume productive work impeded, the dangers to social peace will thereby be aggravated. All barriers are useless in the face of epidemics, especially moral epidemics.

Against all these theories, you may bring up as a decisive factor the rights of victory and of the victors. We recognize these, gentlemen; we are realistic enough in political matters to take this factor into due account. We know our debt in the face of victory and are ready to pay the price for our defeat. But can this be the only principle of reorganization? Is coercion the sole basis for construction? Can material force be the sole sustaining element of an edifice that faces ruin even before its construction is complete? In this case, the future of Europe would be sad indeed. We do not believe, gentlemen, that this could be the mentality of the victorious powers; we do not find these principles in those declarations that you set forth as the ideals of the victory for which you fought and in which you defined the aims of the war.

I repeat: We do not believe that this could be the mentality of the great victorious powers. Do not misunderstand me, if behind the now victorious France, England, and Italy – to mention only the European nations – I evoke the vision of that other France – always the vanguard of noble aspirations and the mouthpiece of great ideas; that other England – the birthplace of political freedoms; and that other Italy – the cradle of the Renaissance, the arts, and intellectual progress. And if I acknowledge, without demur, the right of the victor, I feel quite differently about that other France, England, and Italy; I bow before them in gratitude and gladly accept them as our masters and educators. Allow me, gentlemen, to advise you not to endanger this best part of your inheritance, this great moral influence to which you have a right, by using the weapon of force – a weapon that is in your hands today but may be in another’s tomorrow; preserve unharmed this finest part of your inheritance. […]"

Concluding remarks

"I would just like to say a few more words, gentlemen, on some matters of detail. […] First of all, there is a humanitarian issue – that of prisoners of war.

According to the provisions of the peace treaty, the repatriation of prisoners of war can only occur after the ratification of the peace. I ask you, gentlemen, to refrain from a formality that will cause so many innocent families to suffer.

In the case of those unfortunate prisoners of war detained in Siberia, we have addressed a separate petition to the Supreme Council. In settling this matter, I appeal to your better goodness and humanity – to those feelings that, even in times of war, must rise above politics.

I would like to make one more comment regarding the financial clauses. In my view, the peace treaty does not afford sufficient provision for the special situation Hungary finds herself in. Hungary has had to endure two revolutions, a four-month Bolshevik rampage, and several months of Romanian occupation. Under these circumstances, it is impossible for us to implement the financial and economic clauses envisaged by the peace treaty. […]

Before concluding my remarks, I would like to thank you, gentlemen, for granting me the opportunity to express my views in person and for the courteous and patient attention you have accorded me.

I would also like to say a few words in Italian to show our deep respect for the Italian nation. Hungarian blood and Italian blood were not always shed in opposing camps; they were often shed on battlefields where the two nations fought together against old injustices and in the name of freedom.

I place myself under the protection of these memories so that Italy may provide such support to our legitimate concerns – should such concerns be found to be legitimate – in such a way as is deemed desirable in the principles of justice and the interests of Europe.”

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)