During the Rákosi era (the darkest period of Hungary’s communist dictatorship), the satirical cartoon magazine Ludas Matyi – rather than serving as a source of genuine humor – became one of the regime’s most effective propaganda tools. Its front-page caricatures conveyed official political messages to a broad audience, including the reinterpreted meaning of August 20 (Hungary’s national holiday). The cartoons vividly depict the transformation of the holiday, which traditionally celebrated Saint Stephen, the founder of the Hungarian state. They reflect a process in which values rooted in centuries-old Christian traditions were gradually emptied of their original meaning and replaced with symbols aligned with communist ideology. Saint Stephen’s Day was recast as “Constitution Day,” and the new bread became a central emblem, displacing the Holy Right Hand relic (Szent Jobb). Long-established festive elements, such as the evening fireworks, also quietly disappeared from the official program.

Ludas Matyi in the service of propaganda

Despite the severe shortage of paper, the satirical magazine Ludas Matyi was launched almost immediately after the end of the war, on May 20, 1945. It soon became one of the most important propaganda tools of the Hungarian Communist Party and, later, of the Hungarian Workers’ Party (MDP). At its peak, the paper reached a weekly circulation of nearly 500 000 copies. Although its publication schedule sometimes resulted in a slight delay in responding to major political events, the political caricatures produced by its exceptionally talented cartoonists have since become indispensable sources for the study of the dictatorship.

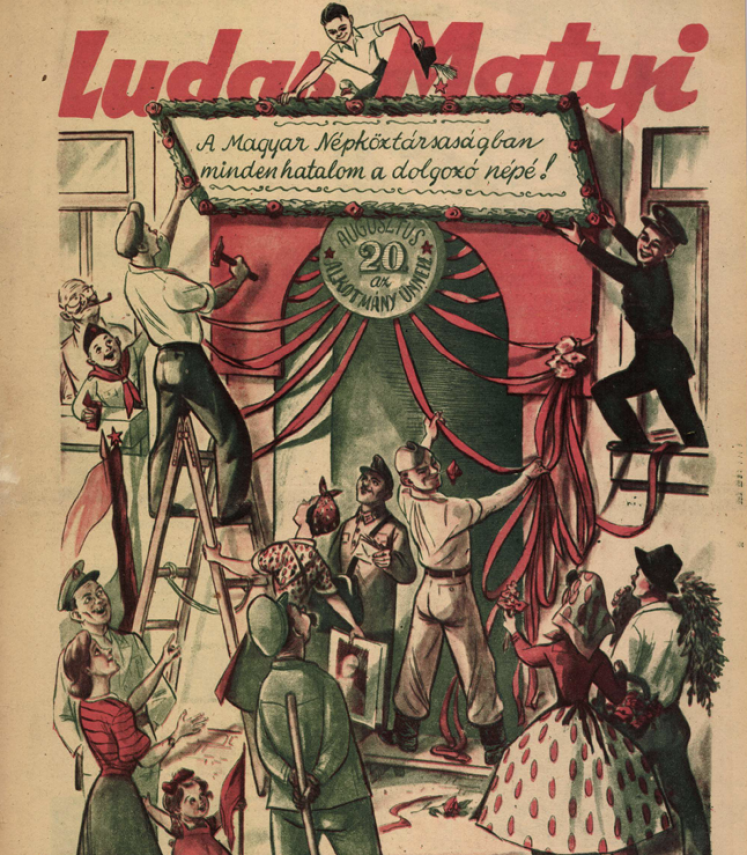

The cover page of Ludas Matyi on August 21, 1948

The eight-page cartoon magazine included around fifty cartoons per week and thus conveyed the Communist Party’s most important political messages to broad segments of society. Although Ludas Matyi featured many cartoons of historical value, the cover drawings were especially prominent, much like editorials in other types of press publications. Since visual representation is often more direct and expressive than the written word, it is worth examining what the cover drawings from the Rákosi era reveal about August 20.

1948: The country still celebrated St. Stephen's Day

Although the procession of the Holy Right Hand of Saint Stephen (Szent Jobb), which had been a regular feature of the holiday since the 19th century, was no longer permitted in 1948, the August 21, 1948 issue of Ludas Matyi nonetheless opened with scenes associated with Saint Stephen’s Day celebrations: a torch relay, a musical morning wake-up call, and an ox roast. The cover cartoon presents these events as imagined by Ludas Matyi himself – the magazine’s wily eponymous character – who, accompanied by his goose, gazes admiringly at the evening fireworks. The fireworks constitute the most prominent element of the composition, forming a luminous backdrop to the entire scene. A vivid cascade of colors dominates the visual field and reappears in a smaller supplementary drawing, further underscoring their central role in the festive imagery.

Another symbol of the holiday also appears on the page: freshly baked bread referred to as “new bread,” and depicted as slices tied with decorative ribbons. The 1948 cover of Ludas Matyi thus presents the visual clash between traditions inherited from a bygone era and those of a new order in the making. While the invocation of Saint Stephen’s name and the presence of fireworks still evoke the historical past, the motif of new bread already points toward the future. One of the new meanings assigned to August 20 by the communist dictatorship therefore emerged as early as 1948. Although new bread played only an episodic role on the Ludas Matyi cover, Mátyás Rákosi’s grandiose speech announcing the collectivization of Hungarian agriculture and the expulsion of the “rich” peasants (kulaks) was delivered in Kecskemét as part of an event titled the New Bread Festival.

Among other factors, this episode has contributed to the widespread belief in public consciousness that the motif of new bread is a product of communist myth-making. In reality, however, the tradition has far more ancient origins. Communist state leaders nevertheless recognized it as a symbolic element that could be readily adapted to their ideological framework and used to reach broad segments of society. In this way, the motif also became an important tool for demonstrating the strengthening of the worker–peasant alliance. From this point onward, organized events became common in which industrial workers visited rural communities bearing tools or machines they had produced, while their hosts welcomed them with new bread.

1949: The publication of the Constitution

The year 1949 can be seen as a turning point in the emptying of the holiday’s original meaning. This was the year when the new Stalinist constitution was introduced, transforming St Stephen’s Day into the Day of the Constitution. Article 67 of Chapter X of the Constitution also defined the new coat of arms: “a hammer and an ear of wheat in a round light blue field, framed on both sides by a wreath of wheat; above it, a five-pointed red star casting rays, and below, a pleated ribbon in red, white, and green.”

The issue of Ludas Matyi dated August 19, 1949 already displayed this newly created symbol of the Hungarian state and the reinterpreted holiday prominently on its cover, filling almost half the page. This emblem later became known as the Rákosi coat of arms. As Szabad Nép, the central newspaper of the Hungarian Working People’s Party (MDP), reported, in 1949 the country was encouraged to celebrate a “double holiday”: the new bread and the Constitution.

The cover page of Ludas Matyi on August 19,1949

The cover of Ludas Matyi was well suited to conveying this message. Alongside the coat of arms held by enthusiastic young people, József Szűr-Szabó’s illustration also featured the new bread. The cartoonist also found an ingenious way to symbolize the worker–peasant alliance: the new bread and the wheat ears of the coat of arms are held by a peasant farmer, while the hammer is grasped by a worker radiating strength.

At the same time, one may wonder why the Constitution – which entered into force on August 20, together with the new coat of arms – was announced a day earlier in Ludas Matyi. The Constitution was formally adopted by parliament on August 18, but both the preparatory work and the approval process had begun much earlier. Shortly after the parliamentary elections of May 15, 1949, the Constitutional Drafting Committee was established on May 27 under the leadership of Mátyás Rákosi. The draft was first discussed by the Political Committee of the MDP on July 28, 1949, and, taking the comments made into account, the working committee (expanded to include Ernő Gerő) was given one day to finalize the text. At the same time, an ambitious campaign plan was drawn up to publicize the Constitution and introduce it to society. This plan was first discussed and approved by the Organizing Committee and subsequently by the Secretariat.

According to the clear instructions of the Organizing Committee, the introduction of the Constitution was to be used to focus on the then barely more than a year-old Hungarian Workers' Party and its leader, Mátyás Rákosi: “the popularization of the Constitution must serve to further unite the Party with the workers, to deepen their affection and gratitude for the party and Comrade Mátyás Rákosi.”

In line with the campaign plan, the party’s central newspaper, Szabad Nép, as well as Népszava and Magyar Nemzet, published the full text of the Constitution (at that point still only a draft) on their front pages on August 7. By August 9, however, all press outlets were required to prepare a detailed plan for popularizing the Constitution. Visual imagery became a key element of the propaganda effort, as the instructions specifically called for the creation of posters featuring the new coat of arms. Ludas Matyi was particularly effective in fulfilling this demand: its cover illustration not only presented the two symbols that would shape the meaning of the holiday for years to come – the coat of arms and the new bread – but also left no doubt about the ideological commitment of the young people holding them, their joyful enthusiasm clearly on display.

Naturally, the nationwide meetings and celebrations held on August 20 – organized mainly by local party bodies – were expected to focus on the presentation of the Constitution, stressing that it marked “another great victory for our Party and for our people’s democracy.” At the same time, in line with the instructions of the Organizing Committee, King Stephen was to be commemorated as the founder of the state, but only in a manner that emphasized that “today the state is the state of the working people.”

1950: The national holiday is enacted by law

Officially, August 20 was declared a constitutional holiday only the following year, by Legislative Decree No. I of 1950 (January 25, 1950), which stated: “August 20 is a national holiday: the holiday of the Constitution of the Hungarian People’s Republic.” Although the new meaning of Saint Stephen’s Day was thus formally enacted by law, Ludas Matyi did not commemorate the first anniversary of the Constitution on its front page.

The explanation lies in international events. After North Korean troops launched an attack on South Korea on June 25, 1950, this conflict quickly came to dominate public discourse, overshadowing even the holiday, despite the appeals of the UN Security Council. The outbreak of the Korean War shifted political messaging toward the fight against the West – labeled “imperialist”– and against the domestic enemy, portrayed as its ally. As a result, both the cover and the majority of the issue were devoted to the Korean War and the struggle against the West.

Despite its official importance, the holiday was pushed firmly into the background. August 20 received no cover illustration, and its visual presence was reduced to a single cartoon occupying less than half a page. This appeared only on page 7, the penultimate page of the paper, under the title “On Constitution Day.”

1951: Still marked by national colors

The cover of the issue published on August 16, 1951, was drawn by Gizi Szegő, who signed her works as gis. It greeted August 20 with a cartoon rendered in full national colors, depicting preparations for the celebration – most likely the decoration of a grandstand. The central element of the drawing is the large sign at the top of the page, also held by Ludas Matyi, which quotes a fundamental principle of the Constitution: “In the Hungarian People’s Republic, all power belongs to the working people.”

It is worth noting that while József Szűr-Szabó’s task on the 1949 cover had been relatively straightforward – reviving familiar motifs centered on the coat of arms – Gizi Szegő faced a far greater challenge by attempting to “draw” the Constitution itself. In keeping with the message of the sign placed by the two workers, the figures celebrating the system – the “working people” – appear primarily as industrial workers, accompanied by a peasant couple in the right-hand corner of the image. As the festivities are still in the preparatory phase, the young man and his wife are not yet bringing the new bread, but rather red floral decorations.

While the caricature’s overall color scheme features the red–white–green national colors, most prominently in the figures’ clothing, the space being constructed is dominated almost entirely by red. Reflecting the content of the new holiday, another key element of the drawing is the circular sign bearing the inscription “August 20, the holiday of the Constitution,” adorned with two red stars.

Only a sharp-eyed reader may notice that Mátyás Rákosi also appears in the image. Following his reported anger at an earlier caricature, depictions of the party leader were no longer permitted in Ludas Matyi. Szegő, however, found an ingenious solution: the blurred portrait on the tableau held by the female figure on the ladder almost certainly conceals Rákosi, while the sheet of paper behind it most likely depicts Joseph Stalin.

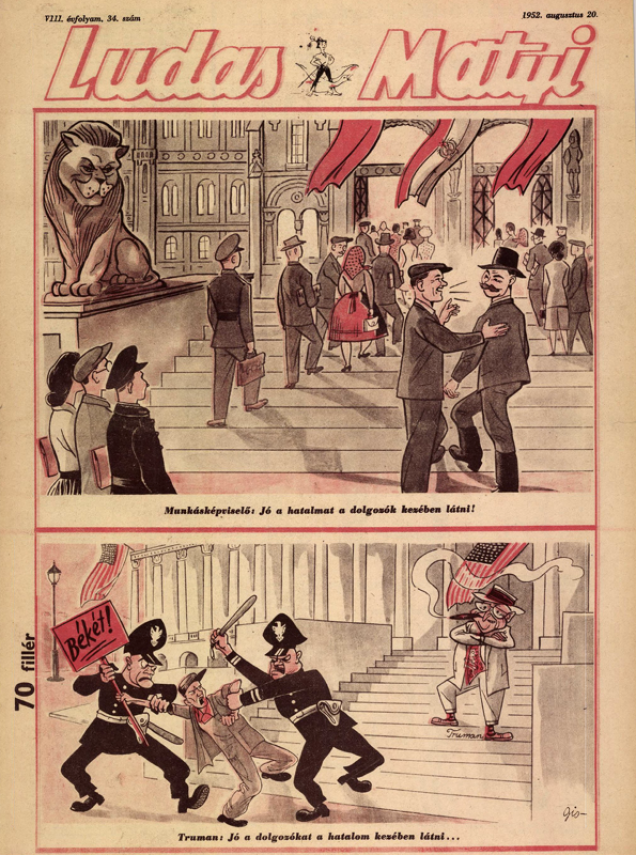

1952: The personality cult at its peak

The August 20 issue appeared on the day of the holiday itself, with Gizi Szegő once again entrusted with creating the festive cover, this time composed of two caricatures. The upper drawing depicts members of parliament, presumably on their way to the festive session. One of them, identified as being of working-class origin, addresses a fellow peasant with the remark: “It is good to see power in the hands of the workers!” The scene can thus be read as a rephrasing of the key sentence from the Constitution that had been visually staged the previous year.

What, then, has changed since that earlier moment, and how? To answer this question, it is worth examining the lower drawing more closely.

The image transports the reader to the United States, where President Truman looks on in silence as a worker demanding peace is beaten by the police. Playing on a pun derived from the quoted sentence of the Constitution, Truman remarks: “It is good to see power in the hands of the working people,” a statement that is immediately undermined by the scene itself.

Against the background of the ongoing Korean War, the American president had become the principal symbol of the Western world, which the newspaper branded as imperialist, making Truman a recurring figure in Ludas Matyi at the time. In this cartoon, however, he appears not only as a warmonger but also as the embodiment of a capitalist system that claims to place power in the hands of workers while, in reality, oppressing and exploiting them. In this way, the image creates a sharp contrast with the socialist order, which presented itself as pro-peace, people-centered, and committed to building socialism. While the upper image projects an idyllic vision of the worker–peasant alliance, the broader context tells a different story. Under the continuing war situation – or, more precisely, through constant reference to it – the five-year plan launched in 1951 brought forced industrialization and large-scale military development, while agriculture was pushed into the background and farmers were steadily stripped of their autonomy. By 1952, the dictatorship, constantly in search of enemies, had reached its darkest year.

Although a Hungarian flag bearing the Rákosi coat of arms appears between the two red flags decorating the Parliament, its green band is replaced by gray, a detail that decisively shapes the image’s overall color scheme. Instead of the balanced effect of national colors that characterized the previous year’s cover, the 1952 image is dominated by red, with gray and black as its accompanying tones.

The year 1952 marked the peak of the personality cult, culminating in Mátyás Rákosi’s 60th birthday on March 9, and can also be seen as the moment when the dictatorship reached completion. From this perspective, the meaning of red itself appears to shift. Beyond its earlier associations with revolution and the building of socialism, the color red, viewed retrospectively, also evokes veres, derived from vér (blood), and can thus be read as the color of violence, aggression, and suffering.

It should be noted that many front-page drawings and other caricatures from this period were published in a similar color scheme, making it impossible to determine with certainty whether this choice was influenced by printing techniques. Even so, there is little doubt that the dictatorship itself is aptly captured by these colors – red.

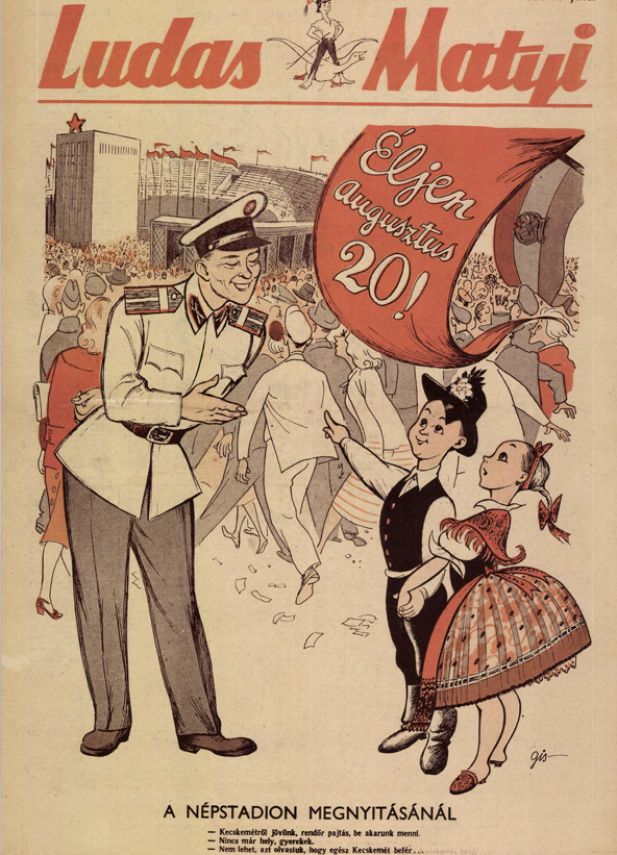

1953: The inauguration of the People’s Stadium (Népstadion)

By August 1953, barely more than a month had passed since Imre Nagy became prime minister, raising the legitimate question of whether the change in the political elite and the relegation of Mátyás Rákosi to the background had led to any shift in the system of symbols conveyed by the paper. This question cannot be answered fully – not only because of the short time that had elapsed, but also because that year witnessed a major event that virtually demanded front-page attention: the inauguration of the People’s Stadium, one of the largest investments of the first five-year plan.

To mark the occasion, Gizi Szegő’s cartoon once again appeared on the cover of the August 20, 1953 issue. The illustration introduced a completely new and distinctive theme, though its colors still recalled that of the previous year. While depicting the opening of the stadium, the cartoonist also emphasized the importance of the holiday itself. The most prominent element of the image is a red flag in the upper right corner bearing the inscription “Long live August 20!”, which visually overshadows the Hungarian flag with the Rákosi coat of arms.

In this sense, a common denominator remains: the very name “People’s Stadium” echoes the ideological principle underlying the Constitution – that everything belongs to the people. It is therefore hardly surprising that the cartoonist did not dress the nation’s stadium in red, white, and green. Instead, the decoration is dominated by red flags and the five-pointed star.

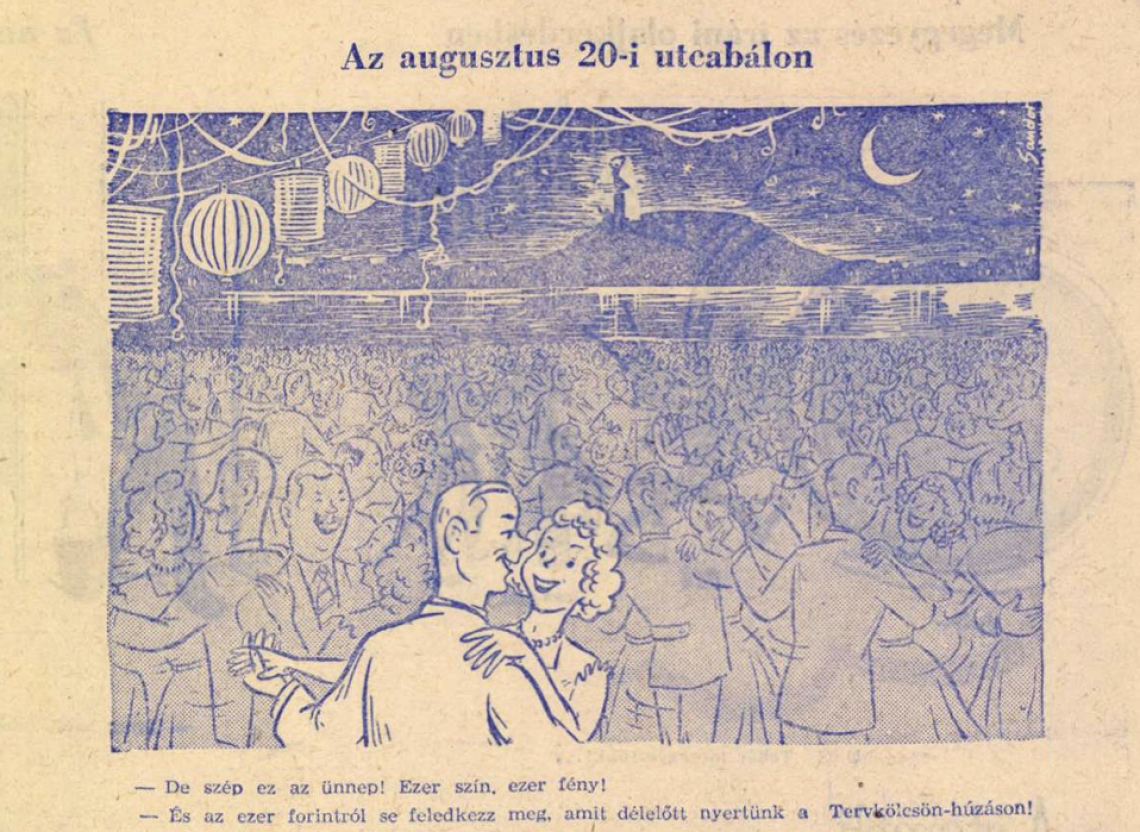

Page 3 of Ludas Matyi on August 19, 1954

1954–1956: interlude and finale

The question of elite change – and, more specifically, the impact of Imre Nagy’s premiership –is particularly relevant in connection with the 1954 holiday issue. Although the newspaper was published on August 19 that year, the idea of the holiday itself is entirely absent from Sándor Gerő’s cartoon on the cover. While the railway cars loaded with coal suggest a continued glorification of industrial development, the issue as a whole is strikingly devoid of praise for the People’s Republic or the Constitution.

In fact, the only cartoon that evokes the holiday appears on page 3 and is only slightly smaller in size. Titled ““At the Street Dance on August 20” ("Az augusztus 20-i utcabálon”), it comes close to a bourgeois visual world. At the center of the image is a dancing couple; the female figure joyfully exclaims: “What a beautiful holiday! A thousand colors, a thousand lights!” The man’s response, however, pulls the viewer back into the social reality of the period, as he replies: “And don’t forget the thousand forints we won in the Plan Loan drawing this morning!”

Paradoxically, despite the monotonous indigo-blue tones of the image and the continued promotion of the Plan Loan, the phrase “a thousand colors, a thousand lights” carries a striking emotional weight. Coming after the heavy-handed propaganda imagery of the preceding years, this moment of fleeting brightness has a surprisingly strong effect, even as it remains embedded within the economic and ideological constraints of the era.

During 1954, the messages conveyed by Ludas Matyi’s cartoons changed markedly, highlighting the differences between propaganda under the premiership of Imre Nagy and during the rule of Mátyás Rákosi. One clear sign of this shift is the near disappearance of caricatures targeting one of the regime’s principal enemy groups – the peasants labeled as kulaks –which had previously appeared on a weekly basis. In their place, more benign figures such as Uncle János and Aunt Juliska emerged, alongside animal characters that recalled Ludas Matyi’s original function as a humor magazine.

After Rákosi’s political position was strengthened once again in March 1955, the full-page cover of Ludas Matyi published on August 18 returned to the Constitution-glorifying themes typical of the early 1950s. By contrast, the cover of the 1956 issue contained only a small caricature referring to August 20, and even this did not focus on the Constitution itself but rather on a lesser-known passage concerning labor competitions.

Although Ludas Matyi covers from the Kádár era continued to celebrate the Constitution, they did so in a markedly different form and with substantially altered content.

(translated by Anna Juhász)