It was a common occurrence for members of nineteenth-century Hungarian parliaments to share family ties with other historical political figures. Family ties formed an important unifying element among the country’s representatives, alongside party or religious affiliations and shared university experiences. These often deliberately pursued family connections ensured not only the preservation of elite power but also the possibility of passing on political knowledge and wisdom. The Tiszas were one such family. In addition to Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza (r. 1875–90) – or the general, as his supporters called him – whose own father was a political figure, there were his two sons (István and Kálmán Jr.), two brothers (Lajos and László), and his brother-in-law (Béla Radvánszky), all of whom served as political representatives for various periods of time.

Although contemporary critics and even older historical literature viewed such family ties as feudal, old-boy networks characteristic of the corporate nature of elite circles, more recent analysis suggests they marked the emergence of a professional group of politicians from within the ruling class of the nineteenth century.

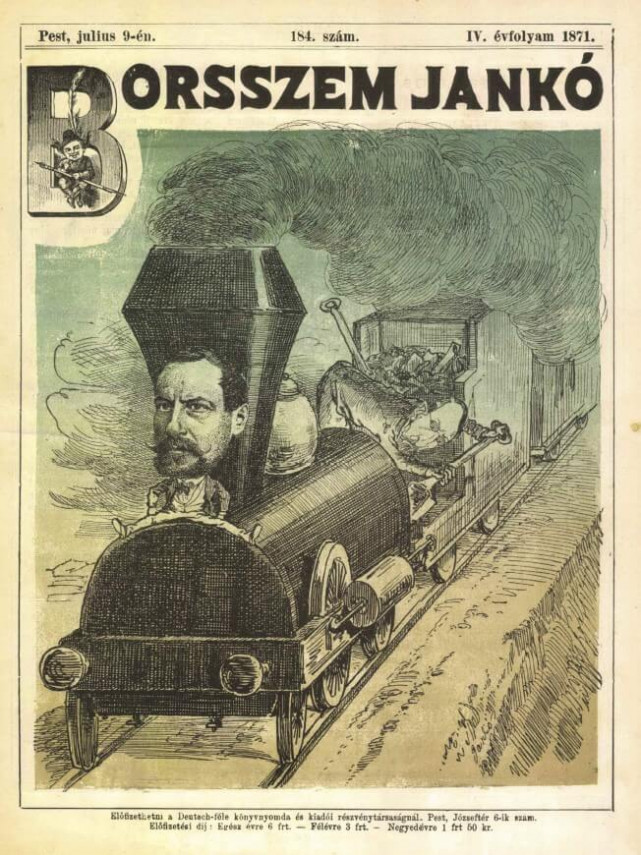

A caricature published on the front page of Borsszem Jankó (Johnny Peppercorn), a Hungarian satirical weekly, upon the appointment of Lajos Tisza as government minister: The younger brother, Lajos, the newly appointed minister of transport, is portrayed as a steam locomotive propelled by his brother Kálmán in the background, July 9, 1871

A political family

Traditional approaches to the exercise of power existed alongside new practices related to political modernization. One study, analyzing the period from 1790 to 1848, was able to identify 25 successive dynasties, spanning three generations and often related to each other, whereas our own research shows that there were at least 19 families – and presumably more – that provided at least six politicians to the parliament in the decades between 1848 and 1892. Even if we narrow the topic down to father-son relationships, we know of at least 210 cases where both father and son(s) assumed roles in the House of Representatives.

A letter written by a young István Tisza to one of his teachers reveals the power of family connections and the conscious choice of a political career as a representative in the Hungarian parliament.

“I have not devoted myself to the study of politics because I believe a political career to be the most rewarding, either here or elsewhere, but out of a sense of duty. Noblesse oblige dictates that those fortunate to be born free from the struggle for existence should thereby devote some care for other concerns.”

Although the Hungarian parliament was often the scene of heated debates at the turn of the century, more touching moments also occured. Sándor Teleki the Younger, for example, noted the following about two members of the Tisza family, the country’s former and future prime ministers, during the last period of the Hungarian parliament, when it held its sessions in the building located on Bródy Sándor Street.

“In a few months the corridor will be demolished, and the new house will not harbor the memories of Kálmán Tisza. […] He loved István very much, and many were the times I saw István kissing his father’s hand in the corridor and his father stroking his head.”

Much is known about the personal relationship between Kálmán Tisza and his son István and their public activities, but their personalities obscure the role of other political members of the family, so we will focus on Kálmán’s two brothers – Lajos and László.

The prodigal son?

The Hungarian novelist and journalist Kálmán Mikszáth (1847–1910), who was well-versed in the political life of the times and possessed a vitriolic pen, described Kálmán Tisza and his two brothers, who were still alive in the post-Compromise era, as follows:

“There are three brothers. Kálmán is too thin, László is too fat, Kálmán is stingy, László is wasteful, Kálmán is a smart, László is not. Kálmán is a large landowner, László is a small landowner. They are opposites in everything. The third brother, Lajos, is unlike either of them – he is the golden mean. […] Kálmán inherited all the great properties owned by the Telekys [Teleki, an old Hungarian noble family], László inherited all the poor ones, and what is good in Lajos came from the Tiszas: diligence, tenacity, and honesty. He received nothing of the Teleky estates.”

Mikszáth evidently did not hold a particularly high opinion of the eldest brother, László Tisza (Geszt, June 27, 1829 – Gmunden, August 28, 1902), even though he also rendered important services in the affairs of state, although not in such a spectacular fashion as Kálmán and Lajos. When the 1848 Revolution broke out, he first joined the Pest Infantry National Guard, which was being organized at the time, and then joined the Hungarian Army (Honvédsereg). In late 1848, however, he was seriously wounded in the Battle of Mór, in western Hungary, and was taken prisoner by the Austrians. Following Hungary’s defeat in the Independence War, he fled abroad, where he attended university alongside his brother Lajos. He subsequently moved to Mezőcsán with his wife, whom he met while still a student, and developed his Transylvanian estate into a model farm. He later became the vice-president of the Transylvanian Economic Association and then, in 1877, its president. He also became involved in parliamentary politics, supporting of his brother Kálmán, and was a member of the Hungarian parliament between 1861 and 1896.

Despite his lowly officer’s rank, László was elected president of the National Veterans’ Aid Society (Országos Honvédsegélyező Egylet) in the spring of 1883.

There are grounds for assuming that Kálmán, who was then prime minister, had tasked his brother to recruit the veterans of 1848 to support the pro-dualist government, as the veterans’ unions, which encompassed numerous rural associations, traditionally operated in accordance with the pro-independent opposition and had a strong influence in shaping public opinion. Close government relations would lead to a significant increase in the society’s budget the year after Tisza’s election as president.

László Tisza, Franz Theodor Würbel lithograph. As a member of parliament, László supported his brother Kálmán’s policies for three decades

László, however, was only partially successful. In 1885, he managed to resolve the renewed controversy surrounding the alleged betrayal of the former Supreme Commander of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army, Artúr Görgei, in 1849. In 1893, on the other hand, he was unable to ensure that the inauguration of the Honvéd Monument, a publicly funded memorial dedicated to the Hungarian independence fighters who liberated Buda from Austrian occupation in 1849, would be held on May 21 and not June 8. While the former date would have commemorated the Hungarian defeat of the Austrian army at Buda in 1849, the latter date coincided with the anniversary of Emperor Franz Joseph’s coronation. László was unable to resolve the conflict over memory politics that accompanied the five decades of Austro-Hungarian dualism, but it was his losing the trust of the National Assembly of Hungarian Soldiers (Országos Honvédgyűlés) that ultimately led to his resignation from office.

Simultaneous with his activities as a member of the veterans associations, László also had to deal with his own financial affairs, although much less is known about the latter, as most of the activities took place out of the public eye. It seems László may have gotten into trouble when the Smallholders’ Land Credit Institute (Kisbirtokosok Földhitelintézete), of which László and a number of other politicians were directors, went bankrupt.

A young Lajos Tisza (1832–1898) with a slightly piercing gaze. Photo J. Borsos

The delegated investigatory committee discovered serious accounting irregularities in addition to finding no trace of numerous monetary disbursements. The case sparked a series of protracted political scandals. László may have suffered a significant loss of wealth and likely sold some of his estates at this time. His creditors garnished his parliamentary salary on several occasions during the 1880s, and his electoral mandate was placed in jeopardy due to his outstanding debts. It can only be presumed that his family hastened to his assistance.

László Tisza had four daughters who reached maturity. They included Ilona, who married her cousin, István Tisza (Kálmán’s son), and another daughter, Anna, who married the lord lieutenant of Kis-Küküllő County and later minister of the interior, János Sándor.

Lajos the rebuilder

László’s younger brother, Lajos Tisza (Nagyvárad, September 12, 1832 – Budapest, January 26, 1898), was cut from different cloth. A somewhat austere political figure who never sought popularity, Lajos possessed a dogged determination which proved more adept in solving practical problems. In addition to his legal studies undertaken in Debrecen and Berlin, Lajos was also acquainted with the turner's trade – either in obedience to his father’s educational precepts or perhaps simply out of personal interest. In 1867, the year of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, Lajos was already a lord lieutenant (főispán) of Bihar County, equivalent to the governor. In 1870, he was appointed vice-chairman of the Budapest Public Works Council, which was formed to develop the infrastructure of the Hungarian capital. This was followed by his appointment as the director of the Ministry of Public Works and Transport from late 1871 to 1873.

Count Lajos Tisza. Painting by Gyula Stetka, commissioned by the National Forestry Association, 1888

Curiously, Lajos bolstered the ranks of the ruling Deák Party, while his two brothers were counted among the ranks of the then opposition Left Centre Party, with Kálmán himself as the latter’s leader. According to malicious gossip, the government tried to diffuse attacks coming from the largest opposition grouping by pushing Lajos to the forefront. In any case, the caricature on the front page of the pro-government Borsszem Jankó suggested it was Kálmán who was propelling Lajos Tisza’s ministerial career from behind the scenes.

Lajos’s government activities can be considered a success, as the unification of Budapest – from the constituent cities of Buda, Pest, and Óbuda – took place during his ministerial tenure, as did the construction of the boulevards in Pest and the overall expansion of the railway network. As an enthusiastic hunter, Lajos also played a role in the creation of the country’s first hunting law in 1872. In 1879, as president of the National Forestry Association (Erdészeti Egyesület), Lajos also contributed to the passing of the Forestry Act, which established sustainable management of the country’s forests. By this time, he was no longer a member of the government, as Hungarian domestic politics had undergone a change. In 1875, the Deák Party merged with the opposition Left Center Party to form a new governing group called the Liberal Party, with Kálmán Tisza soon appointed prime minister. Lajos also joined the new party but did not hold a ministerial portfolio during his brother’s 15-year tenure as prime minister.

The greatest public challenge Lajos ever faced was the devastating Szeged flood of 1879. The Szeged flood claimed 165 lives in the country’s second-largest city, destroyed more than five thousand buildings, and injured more than 14 thousand people. The city requested state assistance, with the parliamentary opposition immediately accusing the government of negligence. Responding to the situation, the king – at the suggestion of the prime minister – appointed Lajos as royal commissioner for the reconstruction of the city. Lajos had a sufficient amount of administrative experience in managing public works and his authority was ensured by his close relationship with the prime minister. Despite initial criticism from several directions – including Lajos Kossuth, who suggested nepotism – the naysayers were eventually silenced after witnessing his great work ethic and constructive initiative.

The Szeged flood, March 1879. Emperor Franz Joseph (in the middle boat) was informed of the tragedy within days. The depiction here is somewhat exaggerated. Only damage control was underway at the time of the emperor’s visit. Theodor Breitwieser lithograph.

During his nearly four-year tenure as royal commissioner, Lajos and his office successfully resolved a very complex set of tasks. In line with government provisions, the legal structures for the reconstruction were established and the financial prerequisites secured. In cooperation with city authorities, Lajos and his commission assessed the damage, managed the threat of epidemics, maintained public safety, and established temporary shelters for homeless citizens. A system of embankments was built to provide lasting protection for the city, and following a contentious series of expropriations, an architectural plan for a modern metropolis was formulated, including boulevards, quays, bridges, and residential buildings. By the end of 1883, investments from state, city, and private sources worth a total of nearly 33 million forints had been made in Szeged, the results of which are clearly visible even today. Lajos usually personally supervised the work. Franz Joseph, who visited the city, praised the results and bestowed Lajos Tisza with the title of count. Lajos would go on to represent one of the former opposition city’s parliamentary mandates from 1884 until his death.

Following this success, it was not surprising that in 1884 the prime minister entrusted the construction of the new Hungarian parliament to his younger brother, who had previous experience in assessing architectural tenders. His main task was to ensure coordination between the activities of architects, sculptors, and contractors and to liaise with government officials. However, neither the architect – Imre Steindl – nor Tisza himself would live to see the completion of the neo-Gothic “Constitutional Church” in 1902.

Lajos Tisza (left) and the painter Mihály Munkácsy during a visit to Szeged. Vasárnapi Újság, 1891

Nevertheless, with Lajos’s assistance, not only was the new Hungarian parliament building built, but a wonderful painting was also created, which can still be seen in the Parliament building to this day. Through the intercession of the novelist Mór Jókai, Lajos asked the painter Mihály Munkácsy, who was living in Paris, to paint a monumental painting for the new building. This became the artwork titled Honfoglás (Conquest of the Homeland), which was finally completed in 1893. Lajos even accompanied the painter on his trip to the Great Hungarian Plain, where he sought suitable objects and faces for his intended painting. Lajos himself sent a bridle from Debrecen for Munkácsy to use in envisioning his scene.

During the last period of his life, between November 1892 and June 1894, and with his brother Kálmán no longer prime minister, Lajos assumed the position of minister beside the king, acting as direct royal representative in Vienna. He assumed this office at a moment when delicate mediation tasks had to be performed to deal with a conflict that had arisen between the king and the Hungarian government and parliament. In matters related to church policy (civil marriage and divorce, freedom of religion, and equal rights for Jews), a disjunct had arisen between the king and domestic liberal forces in Hungary. Ultimately, despite numerous conflicts, Lajos was able to assist the passage of this important package of expanded civil rights and ensure its enactment.

Lajos took part in the leadership activities of numerous social organizations, of which his church activities were among the most important: in 1885 he was appointed chief guardian of the Reformed Church district of Dunamellék, one of four autonomous districts of the Hungarian Reformed Church. Lajos died surrounded by his loved ones on January 28, 1898, following an illness. He was only 66 years old. Lajos had no children of his own, but at his request the king transferred his title of count to his nephew István (Stephen) Tisza and his offspring. His likeness is preserved in Szeged in a statue by János Fadrusz erected in 1904. The artist captured the moment of Lajos overseeing the reconstruction work on the Szeged waterfront.