István Tisza’s second term as Hungarian prime minister is most closely associated with the outbreak of the First World War and, subsequently, with the measures he adopted to ensure Hungary’s wartime endurance. As prime minister, Tisza was directly involved in the decision-making process that led to the outbreak of the Great War, and in the decades that followed, criticism directed at his person increasingly centred on questions of war responsibility. Tisza himself was fully aware of the weight and significance of this issue. In the final days of the war, on 22 October 1918, he addressed the House of Representatives in the following terms: “I beg your pardon, we are placing ourselves in contradiction with the facts, and anyone who seeks to present the matter as though this nation’s warlike passions or aggressive aims had caused either the outbreak of the war or its continuation deprives the Hungarian nation of a great moral asset […]."

In the first half of the 20th century, the Balkans had served as a buffer zone between the Austro-Hungarian and the Russian Empires. The region’s small states confronted the steadily weakening Ottoman Empire, fought each other, and sought support from the great powers to use against each other. As a result of the two Balkan wars in 1912-1913, which altered the status quo, Serbia, which was supported by the Russian government, was significantly strengthened. Bulgaria, which sympathized with the Monarchy, was weakened both militarily and territorially, while Romania, which maintained an alliance with the Central Powers, began to orient itself towards Russia. The Monarchy's weakening position in the Eastern Balkans appeared extremely advantageous for the Russian Empire in the long term.

Tisza's concerns

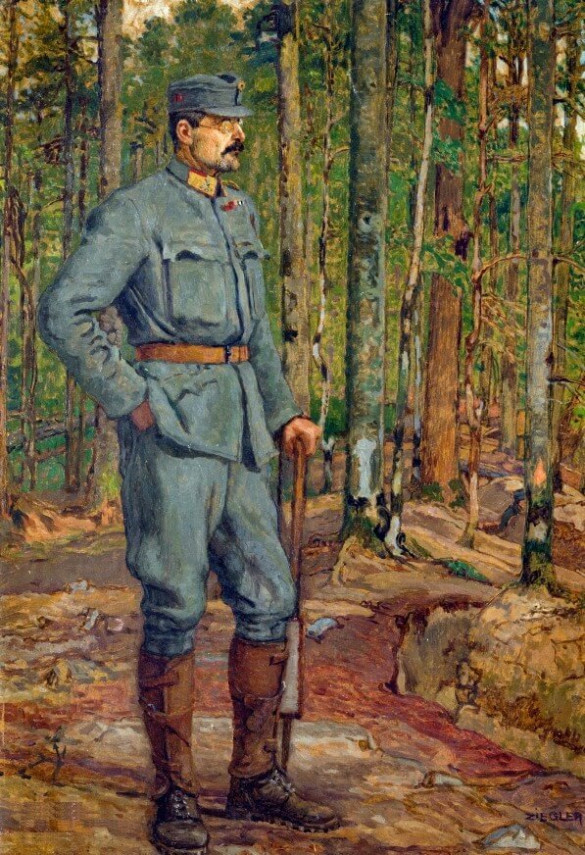

The Hungarian sentry. István Tisza defending his homeland. Lithograph by Dezső Bér, 1914.

Not only were the eastern borders of the Monarchy in danger, but the southern borders were vulnerable as well; the prospect of a looming war evoked an atmosphere of real and imminent threat. Though the leaders of the Monarchy agreed that something would need to be done to counterpoise the changes, they differed on the method to be taken. Military leadership had been urging for war against Serbia since the fall of 1913 with the intent of restoring the Monarchy's prestige as a great power; strengthening Romania's trust and commitment; and, reinforcing Bulgaria's position in the region. Indeed, no one wanted a world war, particularly one in which they considered their army unprepared. Rather, they anticipated a quick, short, regional war to create a favorable position for potential future challenges.

Even István Tisza supported the option of war in the fall of 1913, but only after having exhausted all political means. Through diplomacy, he believed that Serbia could be isolated, Bulgaria could be strengthened as an ally, and the German Empire could exert sufficient pressure on Romania. He also thought an agreement with the Transylvanian Romanians would be conceivable, thus potentially bringing Budapest and Bucharest closer together again.

Tisza’s approach prevailed at the time: there was no preventive war. The policy he advocated required more time than was available; the Sarajevo assassination of 28 June 1914 was seen by Emperor Franz Joseph, Chief of Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf, and Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold as the culmination of Serbian provocation. Given Franz Ferdinand’s well-known hostility toward Hungary, the dualist system, and István Tisza personally, the assassination represented for the Hungarian prime minister, above all, the collapse of Balkan policy, bringing the question of war back onto the agenda.

For Tisza, it was clear that the tactics he had employed in the fall of 1913 would, under the new circumstances, be ineffectual and by the summer of 1914, he saw the military situation become increasingly unfavorable. He was by no means a pacifist; he considered the outbreak of a major war to be inevitable and ill-timed. Convinced that military intervention could not be kept within local boundaries, he expected Romania to become hostile and was quite certain that Russia would intervene on Serbia's side – precisely the course of events the Monarchy wanted to avoid.

He had no doubt that a war on the Serbian−Romanian−Russian front would inevitably take place on Hungary's borders, and that a possible defeat would have unforeseeable consequences for the integrity of these territories. His position, however, was significantly influenced by the German Empire’s pro-war stance; in the event of an escalation of war against Serbia, the Monarchy could count on German weapons to be used against Russia. Bearing this in mind, Tisza continued to express his concerns and took steps to delay the process in order to minimize the possibility of an armed conflict that he hoped would remain local.

At a joint cabinet meeting on July 7, 1914, he advised that Serbia be given a feasible ultimatum and that war be considered as only a last resort. Everything was to be done so as to localize the armed conflict and, in the case of victory, Serbia should not be annexed. Parts of its territory, however, could be given to Greece, Albania, and Bulgaria. Tisza was convinced that a declaration would potentially reduce the likelihood of Russian intervention. He expressed this view in a memorandum written to the emperor the following day. At the following cabinet meeting on July 14, the Hungarian prime minister was able to push his agenda through: the ultimatum’s phrasing was not rejected, Tisza received the necessary guarantees from the Germans regarding Romania; he received a promise to strengthen the defense of Transylvania, his proposal for an alliance with Bulgaria was accepted, and, it was voted that Serbian territories would not be annexed.

There’s no other way

With Vienna and Berlin having clearly taken sides in the war against Serbia and apparently prepared, if necessary, to risk a world war in a conflict that mainly threatened the southern and eastern borders of the Monarchy, Tisza found himself in a precarious political situation. If, as Hungarian prime minister, he maintained his opposition to war in the face of the monarch, he would have to resign from office leaving Hungary to contend with a government crisis at a very critical time. For Tisza, a man of challenges and action, this was not an option.

One must not forget that German and Austrian politicians exerted pressure on the prime minister to go to war, and the opposition and public opinion likewise demanded decisive action against Serbia. As the Hungarian head of government, Tisza feared that if he backed out of the conflict, the Monarchy would lose the support of its ally, the German Empire. The dualist state and Hungary, whose territorial integrity was being threatened, clearly needed their ally in the face of Russian expansionist ambitions.

As this option appeared to be decidedly disastrous and by bearing in mind that a positive outcome of a war against Serbia could not be ruled out, Tisza abandoned his rejectionist stance, taking into account the promises he had requested and received. The ultimatum was finally delivered on July 23 by the Monarchy's ambassador in Belgrade. It was rejected by the Serbian government the following day, leading to the Monarchy’s declaration of war on Serbia on 28 July and subsequently triggering a series of further declarations of war.

István Tisza's responsibility as prime minister is indisputable, since – after three weeks of procrastination – he did indeed contribute to the outbreak of a protracted war that brought suffering on an unforeseen scale. He believed that Hungary faced a threat that could only be averted by a victorious war. However, unlike many of his contemporaries and other European government leaders, he was not overcome with enthusiasm. When he received a delegation from the Hungarian Workers' Disabled and Pensioners' Association in the days following the declaration of war, he stated:

"War is a horrible thing. Believe me that I have felt and experienced all the horrors of war – and [I felt] the full weight of responsibility that comes with starting a war in those days when I too had to take part in the decision."

He expresses himself even more clearly in a letter written to his niece, Margit Zeyk, on August 26, 1914:

"In my soul, every war means misery, suffering, destruction, the shedding of innocent blood, and the suffering of innocent women and children. It saddens me that I am party to such a great war. The ovations directed at me hurt, even though I cannot even take part in the fighting. My conscience is clear; the noose was already around our necks, and had we not cut it now, they would have strangled us at a more opportune moment. We had no other choice, but it is still painful that it had to be this way."

These statements in no way reflect the thoughts of one enthusiastic about war. Whatever his official statements may suggest, Tisza was clearly weighed down by the burden of war.

The Monarchy’s Strong Man

World War I broke out on July 28, 1914. Subsequently, Tisza focused all his attention to maintaining internal peace and maximizing military efficacy by ruling Hungary with a firm hand. For a significant period of time his political approach was effective: Hungarian society persevered and the economy continued to function despite the Hungarian government’s need to devote increasing attention to disabled war veterans, war orphans, and the organized distribution of food to the public due to escalating losses. When the Russian army invaded Hungary and when Romania attacked Translyvania in 1916, special measures were required in terms of both organizing defense and accommodating refugees. It was not a coincidence that Tisza was referred to as the strong man of the Monarchy by the Entente powers, and that he was one of the Central Powers’ pillars of resistance during the war.

István Tisza, the soldier

It was for this reason, among others, that as early as February 1917 the decidedly ambitious King Charles IV, ascendant to the throne following the passing of Franz Joseph, would have preferred to see someone else in the Hungarian prime minister’s seat. Tisza objected to the monarch’s position concerning internal reforms –most particularly the expansion of suffrage – and thus, after several months of maneuvering, Tisza submitted his resignation on May 23, 1917. He was initially succeeded by Móric Esterházy; then Sándor Wekerle stepped in to serve his third term as head of government. Assessing the year-and-a-half following Tisza’s resignation, however, one could confidently argue that the minority government of the time was characteristically and administratively stagnant in all areas. The monarch’s aim to stabilize conditions in the country and extend suffrage in Hungary through Tisza’s removal, failed. For all intents and purposes, the tense political situation caused by the severe soldiers’ crisis and provisions crisis in early 1917 only exacerbated the already tense domestic political situation with further government crises and ineffectual parliamentary debates.

As an inactive-status colonel, István Tisza left for the battle field to join his unit, the 2nd Royal Hussar Regiment on August 10, 1917 – doing so despite his age of 56 and his poor eyesight. He took command over the regiment but continued to participate in parliamentary sessions as the leader of the majority opposition. He also closely monitored developments on the international scene, namely Russia’s threat to Hungary’s integrity. It was the collapse of Tsarist Russia that he considered to be the most crucial foreign policy change during the war. In his speech to the House of Representatives on November 23, 1917 he stated:

“Honourable House! Regarding the event of which we learned from yesterday evening’s or this morning’s newspapers, [...] namely, that the current ruling party in Russia has ordered the army's high command to request a ceasefire from the Allied Powers with a view to initiating peace negotiations. [...], it would be pointless to deny or obscure the fact that this news fills us with inner joy and satisfaction. This joy and satisfaction arise, first and foremost, from the fact that from the very beginning of this war we have been compelled to fight a defensive war out of necessity […], since the aggressive and expansionist policy of the Russian government at the time threatened our very existence. We would have continued this struggle for not a single minute longer than was necessary to avert this danger to our vital interests. If, indeed, this threat has now been averted as a result of the changes that have taken place in the Russian Empire, this development will surely be received with great and unanimous satisfaction by Hungarian public opinion."

The separate peace that was concluded with the Russians considerably reduced the burden on the military leadership. The Balkan and Italian fronts, however, could only be held at the expense of tremendous sacrifices. It also became clear, following the German defeat on August 8, 1918, that the French and British forces could not be broken in time – prior to the arrival of their allies, the American troops. The Entente launched a general offensive on various fronts beginning with the Balkans. Within days of the offensive, on September 15, the Bulgarian front collapsed in Macedonia − followed by a request for armistice on September 26. Bulgaria’s withdrawal was soon followed by Turkey’s after the Turkish front lines in Palestine were broken through on October 18.

Tisza’s last political mission, a thirteen-day trip to South Slavic territories (September 13-25, 1918), coincided with Bulgaria’s collapse. Béla Nádasdy, a lieutenant colonel in the general staff who was assigned to accompany Tisza, provided a detailed account of the trip and its key moments. Based on the available information, Tisza’s trip to the south was most likely connected to the King’s efforts to promptly resolve the South Slavic question. The King’s aim was to have Tisza, the leader of the majority party, study the South Slavic issue in situ so as to personally inform him of the political mood gained through wide-ranging discussions.

Marking the climax of his exploratory trip, Tisza’s well-known and steadfast position on the Hungarian–Croatian union was articulated in Sarajevo on 12 September. Having been presented the previous day with the “South Slavic Declaration” by its delegation of signatories, Tisza responded with what contemporaries described as a “thorough and appropriately harsh berating,” invoking the “immovable borders” of the dualist Hungarian–Croatian state. Whether this negotiating strategy was appropriate remains doubtful; nevertheless, despite the gravity of the situation, Tisza was determined to project strength in the face of South Slavic unification efforts.

The attempt at cooperation

Andrássy presents the following vivid image of the internal conditions at the end of September from a military point of view:

“The minority Wekerle government, which is unable to implement its program, is internally divided and is under the influence of its opponent, Tisza. Social democracy is connected only to the most radical party [...] The platform of suffrage is increasingly being pushed into the background by the pacifist, anti-militarist platform. Defeatism is spreading rapidly. The decaying government opens wide doors to agitation, which begins to poison the army's reserve formations. Disobedience is the order of the day in the navy and the army. [...] The anarchy of the periphery is exacerbated by the anarchy of the center. Party strife, the clash of ambitions, the rush forward of those who believe that they alone can save the nation [...], further agitate the mood [...]. There is a great danger that the internal front will collapse before peace is concluded, and we will be at the mercy of the enemy."

Completing the picture, responding to the alarming influence of the Bulgarian news, Wekerle gave a reassuring statement to the press on September 28, emphasizing the need to create a unified domestic policy in the country. On September 30, Tisza took a similar approach when he declared among National Party of Work members:

"...first and foremost, the most important task is for all honest Hungarians to unite and to establish a strong political front alongside a strong military front."

Such cooperation would, in practice, mean the formation of a grand coalition government. On October 22, 1918, Tisza commented on this with his following speech:

"We must do everything in our power to ensure that we, the Hungarian people, understand one another and stand shoulder to shoulder in the defence of our nation’s vital interests. I would very much like to see this common resolve reflected in shared participation in government. Unfortunately, at present I perceive obstacles that appear insurmountable – namely, the presence of certain influential figures in public life with whom I nonetheless regard full cooperation as essential for the good of the country under the present circumstances. If these obstacles can be overcome, so much the better. If they cannot, then let us at least endeavour to cooperate from our respective positions in the joint defence of the nation’s interests. And let those for whom this obstacle does not exist unite, so that the Hungarian government may enjoy the support of as broad a majority as possible in the Hungarian House of Representatives, thereby enabling it to act with the authority that only the backing of a parliamentary majority can confer.”

On October 17, 1918 he had already made clear what he considered to be the utmost duty of Hungarian elites. The goal and intention was the creation of a grand coalition:

"I repeat, Honourable House, the task that awaits us all regardless of party differences, is to make peace based on the terms set forth by Wilson's 14 points, [and to make it] as advantageous as possible for the Hungarian nation. […]; to ensure the territorial integrity of the Hungarian state, […] which Wilson's 14 points did not attack at all, but – because this alone, of course, is not enough– to ensure the unity and internal cohesion of the Hungarian state as well."

At their final meeting on the evening of 22 October, Tisza reported to the members of the National Party of Work on the outcomes of his negotiations with other parties. He stated that, with the exception of Károlyi’s party, he had approached all major political groups regarding cooperation and the possibility of a merger. Although representatives of the Apponyi–Andrássy group, Dezső Bizony’s Independence Party, the Smallholders’ Party, and the Democrats expressed their willingness to cooperate in safeguarding national interests in relation to the war and the achievement of peace, they did not consider a merger feasible. Under these circumstances, closer ties were established only between the 1848 Constitutional Party and the National Party of Work.

Even in these circumstances Tisza took a liberal-minded step: at a meeting of the National Party of Work, the party with parliamentary majority, it was decided that it would merge with Wekerle’s 1848 Constitutional Party. With the members of National Party of Work, the Wekerle government would have a sufficient majority, thus changing the balance of power in parliament. On October 23, during the recess of the House of Representative, party leaders held a meeting in the prime minister’s office where they agreed to form a national coalition involving all parties with the following three program points:

1. universal, equal suffrage, by secret ballot,

2. the territorial integrity of Hungary,

3. the complete independence of Hungary.

Tisza conceded once again. He agreed that the Károlyi Party should be a member of the anticipated coalition government, but adamantly opposed the formation of an independent Károlyi government. By including Károlyi in a grand coalition government, Tisza’s obvious objective was to pacify and temper him as much as possible. He declared that, under the circumstances, he would accept the three program points as well as agree to universal suffrage. Perceiving the country to be in grave danger, he was willing to make this sacrifice in the hope that it would serve the country well. Following this meeting of party leaders, Wekerle announced the government's thrice-repeated resignation.

The looming collapse

Hopes were quickly dashed: Tisza’s vision of a unified Hungarian state, or “national concentration” of parties, did not come about. Contrary to what had been agreed upon earlier that day, on the night of October 23, Károlyi and his supporters decided to form a Hungarian National Council, emulating the national councils already established in Austria. Subsequently, in a proclamation issued on October 26, the Hungarian National Council declared itself the counter-government of the Hungarian nation and called upon the entire country to join it. The government crisis had reached a stalemate.

On October 24, despite the agreement reached by party leaders the previous day, Károlyi wanted to form a government under his own chairmanship and based on his own program. On October 29, he sharpened this plan by stating that he wanted to form the planned government exclusively from parties represented in the National Council. Thus, neither the party leaders' discussions on the 23rd, nor the royal hearings held in Gödöllő between October 24 and 26, nor Archduke Joseph's negotiations in Budapest on the 28th in his capacity as homo regius yielded any meaningful results. The reason for the failure of the negotiations is articulated in a letter from Tisza to his daughter-in-law on October 26:

“The Wekerle government resigned because they argued that national unity could [only] be achieved if we abandoned our position on suffrage. On the other hand, the deterioration of the general situation, and especially relations between Austria and Croatia, made it seem all the more necessary for the semi-patriotic and decent elements to unite. We made the sacrifice: we declared that suffrage could not be an obstacle, and now, for three days, the ugliest squabbling has been going on, and in times like these, the country is left without a leader. Károlyi and his followers are striving for outright Bolshevik rule, and the great patriots do not dare to undertake anything without them or against them. Meanwhile, what could perhaps still have been saved is being destroyed and ruined. It is truly shameful and outrageous.”

It was in this context that the 1848 Constitutional Party held a meeting on October 28, 1918 at which Tisza made his last public statement:

"All of us who have gathered here have the task of aiding the development of the country; we must provide staunch support to those who want to save this country from anarchy. Furthermore, we must enable the government, even while it is conducting affairs as a resigned government, to maintain order in the country under all circumstances and spare this country from the trials and tribulations of a revolutionary parody. The situation in the country is quite grim, because, after all, it appears that we must reckon with our enemy's far-reaching hostility. However, what would make the situation catastrophic would be if they succeeded in disrupting the internal order of the country; were the government of the country to crumble into the dust of the streets. Regardless of party differences, it is the primary duty of every Hungarian citizen to spare their nation from this blow.”

Tisza’s political opponents did exactly the opposite of what he had proposed, the results of which are well known. István Tisza, however, did not live to see it. He was assassinated on October 31.

(translated by Andrea THürmer and John Puckett)