Erzsébet (Elizabeth) Szilágyi de Horogszeg was – in accordance with the expectations of her time – a family-oriented wife and mother, a strict and energetic landowner, and a devout Roman Catholic. However, it was not these qualities that had a major role in making her famous; rather, it was the fact that she was the wife of János (John) Hunyadi, the renowned fifteenth-century Hungarian commander who defeated the Turks, and the mother of Mátyás (Matthias) Hunyadi, for whom she made determined political efforts to ensure his elevation to the throne. With Mátyás’s rise to power, this widow from the lesser nobility became the royal mother. All this made Erzsébet Szilágyi one of the most famous female figures in medieval Hungarian history.

The Szilágyi family coat of arms

Erzsébet Szilágyi de Horogszeg, the daughter of László (Ladisalus) Szilágyi Bernolt and Katalin Bellýeni, was born around 1410-1411. According to current theories, the Szilágyi de Horogszeg family may have originated in Szilágyság, a historical region formed by the former Hungarian counties of Közép-Szolnok and Kraszna (now in northwestern Romania), but this remains conjecture. Her mother likely came from a landowning family in the southern part of the country. Her father first served as alispán, or deputy lord-lieutenant, of the counties of Valkó and Bács, under János Maróti, the Ban of Macsó, then as one of the castellans of Srebrenik; and later became a judge in the twin market towns of Szatmár and Németi under István Lazarevics, the Serbian despot.

Family background

Erzsébet had five siblings: Orsolya, Zsófia, László the Younger, Mihály, and Osvát. We know almost nothing about her youth. She probably met her future husband, János Hunyadi, around 1426–1427, as he – like Erzsébet’s father – was in the service of the Serbian despot, Lazarevics. The young couple likely married soon after. The year of their first (known) child, László Hunyadi’s, birth is uncertain: according to the fifteenth-century Celje (Cillei) Chronicle and the records kept by the Hungarian court historian Antonio Bonfini, Erzsébet gave birth to László in 1431, whereas according to Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, later Pope Pius II, and the chronicler Gáspár Heltai, László was born in 1433. The couple’s second son, Mátyás, was born on February 23, 1443, in Kolozsvár, in the house of the vineyard owner Jakab Méhfi. The long separation in births between the two Hunyádi brothers may point to the possibility of other offspring who presumably died in infancy.

Erzsébet likely did not play a significant role in her sons’ upbringing. Only two written sources from the time of her marriage survive. In a document dated 1441 and preserved in extract, Erzsébet instructs the tax collectors of Temes County not to collect taxes from one László, the headman of Barátfalva and her faithful servant. In a letter dated October 23, 1455, written in Hunyad County and addressed to John of Capistrano, Erzsébet urges the Franciscan inquisitor to pray for her seriously ill daughter-in-law, Erzsébet Cillei – wife of László Hunyadi, in Hunyad. Despite the entreaties, the young countess died soon after. But Erzsébet Szilágyi would soon endure further, even more painful family losses.

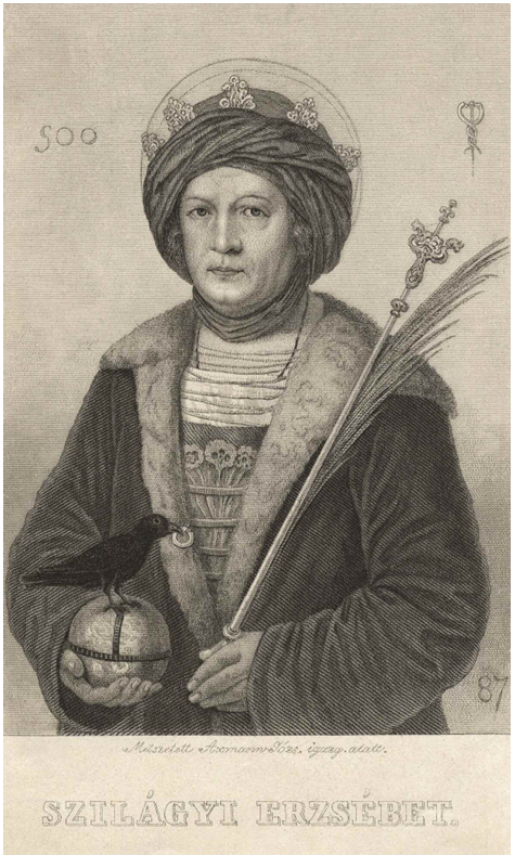

Erzsébet Szilágyi as depicted on an ivory medallion once belonging to the family of the Hungarian novelist Baron Jósika. Collection of the National Museum of the History of Transylvania in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca).

On the national political stage

On August 11, 1456, János Hunyadi fell victim to a plague epidemic that broke out at a military camp in Zimony, outside of Belgrade. No sooner had she become a widow than Erzsébet Szilágyi had to worry about the lives of her sons, especially László. On November 8, 1456, László essentially took Ladislaus V – Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia – and his entourage hostage when they arrived in Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) to take possession of the fortress, of which László Hunyadi was the commandant. The next day, László and his knights murdered the king’s great-uncle, Ulrich II, Count of Celje. László then led the king and his entourage through Keve County to Temesvár, where his mother and younger brother received them.

According to the chronicler János Thuróczy and the accounts of Pietro Ranzano and Antonio Bonfini, Erzsébet thereupon asked the king for forgiveness, who in turn graciously promised that he would not take revenge on the Hunyadi brothers for the death of Ulrich of Celje. Although Ladislaus V did indeed guarantee in writing at the end of November 1456 that he would leave the murder unpunished, current scholarship is of the opinion that it was not so much the pleas of László Hunyadi or his mother but the fact that he was László’s prisoner that forced the king to pronounce forgiveness.

However, soon after regaining his freedom, the ruler had László, his younger brother Mátyás, and several of their followers arrested in Buda on March 14, 1457. Two days later the elder Hunyadi was beheaded in St. George’s Square. Erzsébet Szilágyi thus lost her eldest son after her husband, while her younger son was taken away from her. In response, the widow and her brother Mihály launched an armed uprising against the king and his loyal court.

Actions of the Szilágyi siblings

In order to increase their military strength, Erzsébet and Mihály formed an alliance in 1457 in Temesvár with the Pongrác family of Szentmiklós, from northwestern Hungary. To avoid an outright battle, Ladislaus V fled with his prisoners, including Mátyás, first to Vienna and then to Prague in the autumn of 1457. Several attempts at peace were made between him and the Szilágyis, during which the king’s envoys proposed the return of the royal castles that had been seized as a condition for the release of the Hunyadi leaders. But before the negotiations could come to fruition, Ladislaus V died unexpectedly in Prague on November 23, 1457. He was 17 years old.

The subsequent interregnum between kings marked the most important turning point in Erzsébet Szilágyi’s life: the opportunity arose of making her sole surviving child the King of Hungary. Although the foreign candidates – Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, and Casimir IV, King of Poland – were unable to assert their claims, Erzsébet and her brother Mihály still faced serious opposition in the form of Miklós Újlaki (Nicholas of Ilok), Ban of Macsó, and László Garai, Palatine of Hungary.

For the Szilágyis, it was crucial from the perspective of legitimacy to win over the palatine – the highest-ranking official in the country – to their side. They succeeded in doing so by forging an agreement with the Garais on January 12, 1458, in Szeged, in which, among other things, László Garai renounced his claim to the throne and promised to support the election of Mátyás Hunyadi as King of Hungary; in return, Erzsébet and Mihály forgave Garai for his participation in the execution of László Hunyadi. The parties also agreed that Mátyás would marry the palatine’s daughter – Anna Garai – and only after the consummation of said union would Mátyás be provided unencumbered inheritance of his family estates and the kingdom.

Since Miklós Újlaki was an ally of Palatine Garai, the agreement also indirectly secured the former’s support as well.

Once all obstacles had been removed, the Diet of Pest, in which Erzsébet naturally participated, met in early 1458 and elected Mátyás Hunyadi as King of Hungary on January 24, with his uncle – Mihály Szilágyi – as regent. Then, a delegation led by Erzsébet and Mihály set off for Bohemia to bring the young ruler home. Upon learning of these developments, the regent of Bohemia, George of Poděbrady – who had been holding Mátyás captive – left Prague with the newly elected king, and the two delegations met on February 5 in Strassnitz.

Four days later, Mátyás and George concluded an agreement in Strassnitz in which they declared eternal friendship and fraternal alliance, and as a pledge of this, they confirmed that – in accordance with an earlier agreement in Prague – Mátyás would marry George’s daughter Catherine. Erzsébet and Mihály were unaware of the agreement made with George in Prague, and since the obligation to marry Catherine went against the agreement to marry Anna Garai concluded in Szeged, they were understandably reluctant to recognize the young king’s decision. However, having no other choice, they were forced to approve it, so they affixed their seals to the Strassnitz agreement as well.

Family feuds

Erzsébet Szilágyi not only elevated her son to the throne, but she also supported him in consolidating his power. Upon returning to Buda, the new king could not be crowned with the Holy Crown, as it was then in the possession of Frederick III. Without this, Mátyás could not be considered a completely legitimate ruler. Thus, in order to enforce his will more effectively, he was forced to have his documents officially sealed by other persons or obtain their verbal consent for his measures. In this the young king was also assisted by his mother (and uncle) during the first few months of his reign.

In addition to enforcing Mátyás’s royal will, Erzsébet also defended her son against anti-royal plotters, whose ranks had been joined by her own brother Mihály. Due to Mátyás’s violation of the Szeged agreement and Mihály’s subsequent resignation as regent, the latter had turned against his nephew. In the conflict between her son and brother, Erzsébet mostly acted as mediator but was not above confronting Mihály on Mátyás’s behalf. In 1458, the regent held discussions with the Brankovics in order to obtain the title of Serbian despot. In exchange for the fortresses of Szendrő and Galambóc, he was to return to them the valuable Hungarian estates of the late despot George Brankovics. In a charter issue in Buda on June 23, 1458, Erzsébet vetoed the agreement – presumably at her son’s request. When Mihály Szilágyi joined the anti-Mátyás alliance in Simontornya, on August 8, Erzsébet helped smooth over the differences with the assistance of János Vitéz de Zredna, Bishop of Várad.

Although Mihály had resigned from his position as regent, he continued to plot against his nephew, who thus had him arrested on October 8 and imprisoned in Világosvár, a mountain fortress in the Mátra Mountains. Mihály Szilágyi escaped the following summer and began plotting against Mátyás once again. Another attempt was made to settle their differences in the autumn of 1459 when Erzsébet intervened in Buda once again in order to restore family peace – this time with the assistance of Dénes Szécsi, Archbishop of Esztergom, and István Várdai, Archbishop of Kalocsa. However, final reconciliation between the king and his uncle did not take place until the spring of 1460 – according to Bonfini – when they met on the banks of the Tisza River between the towns of Várkony (Tiszavárkony) and Varsány (Rákóczifalva) in former Külső-Szolnok County. Although there is no written evidence to support this, it cannot be ruled out that Erzsébet was present here as well.

To found a dynasty

Erzsébet Szilágyi would contribute not only to the consolidation of her son’s power but also, to a certain extent, to its perpetuation; that is, she was able to influence the founding of a ruling dynasty. In connection with the betrothal of Mátyás, who was 18 at the time, and Catherine of Poděbrady, who was 11, the widow was granted the right to have a say in determining the date of the wedding night. According to Mátyás’s marriage certificate, issued on January 25, 1461, the marriage was to be consummated two years after the wedding, which was originally planned for May 1 of that year, on account of the bride’s young age.

However, in the opinion of the high priests, barons, and his own mother, Mátyás could hasten this event if he deemed it appropriate. Erzsébet Szilágyi was likely also part of the delegation that welcomed Catherine of Poděbrady upon her arrival to Hungary, in Trencsén, in early June 1461, in addition to attending the wedding held a few weeks later.

Mátyás Hunyadi’s second royal marriage (he had been married briefly in 1455 to Elizabeth of Celje, who died within a year) ended tragically: his young bride died of childbed fever on February 23, 1464, shortly after giving birth to their newborn son, who lived only a few days. A month later, on March 29, 1464, Mátyás was crowned with the Holy Crown, which had been recovered from Frederick III shortly before, making him the legitimate king of Hungary. Although we have no record of this, Elizabeth was almost certainly present at the event.

Zsigmond Vajda’s 1890 painting of Erzsébet Szilágyi and the young Mátyás Hunyadi. János Hunyadi, the hero who defeated the Turks, is depicted in the background

Erzsébet the landowner

Erzsébet Szilágyi spent most of her time during her son’s reign managing her estates. In 1461, Mátyás granted his mother a market-town estate at Böszörmény-Debrecen, which she had previously owned for a short while, along with the castle in Munkács and its appurtenances. Two years later he also conferred upon her another market-town estate at Szentandrás–Donáttornya. These became Erzsébet’s primary landholdings.

In managing her estates, Erzsébet defended and increased her privileges or restored them when necessary. On several occasions she prevailed upon local officials in Debrecen to respect the duty-exempt status of merchants from Kassa, Bártfa, and Szentgyörgy when visiting her market towns. In addition – and at his own request – King Mátyás conferred upon the residents of Debrecen the privilege of a nationwide exemption on duties, while Erzsébet granted her subjects in both Debrecen and Újváros (Balmaz) the right to make wills. At the request of the inhabitants of Debrecen, Erzsébet was also willing to restore their previously revoked privilege of appealing to the Buda town council instead of local officials in their legal cases.

When Erzsébet visited her estate in Munkács in the autumn of 1466 and saw the dilapidated state of nine Vlach villages belonging to it, she granted their inhabitants a number of privileges, including a significant reduction in their tax burden – both monetary and in kind – and a five-year tax exemption for all new residents. In 1463, she instructed one of the local officials in Szentandrás to procure a new specialist to complete the construction of the manor house on the estate, replacing the previous foreman who had been transferred elsewhere. At the same time, Erzsébet also instructed her estate manager to reward a Cumanian for his loyal service by gifting him a horse. Erzsébet also issued instructions for additional tasks to be performed on her estates, such as purchasing livestock for slaughter, smoking meat, measuring wine, and collecting taxes

When dealing with abuse of power or damage to property, she always called on the guilty to make reparations, whether they were her own people or other landowners or their subjects. Erzsébet did not tolerate injustice or disobedience among her chattels, which sometimes elicited very violent reactions on her part. When she learned that the inhabitants of several settlements belonging to the estate at Szentandrás failed to obey the steward János Teleki Varjasi, whom she had appointed to manage the estate, she ordered them to comply in a harsh tone, threatening them with the loss of their property and having their eyes gouged out.

Erzsébet’s religious life

Written sources also provide insight into Erzsébet Szilagyi’s church connections and religious devotion. As the wife of János Hunyadi and later the mother of King Mátyás, Erzsébet’s name was also known at the Holy See in Rome. In the 1440s, both she and her husband, János Hunyadi, received letters of pardon and absolution from Pope Eugene IV, and then in 1458 Pope Calixtus III sent her written congratulations on the election of her son as king and her brother as regent. In 1459, Erzsébet and Mátyás appealed to Pope Pius II regarding the injustices suffered by the Dominican nuns on Nyulak (Margit) Island. In 1465, Pope Paul II presented the widow (and her son) an agnus (a wax reliquary depicting the Lamb of God), and in 1470, the same pope granted the right to collect tithes for the Saint Mátyás Church founded by Erzsébet in the market town of Újváros. On August 8, 1473, Erzsébet sent a letter to Pope Sixtus IV urging him to canonize John of Capistrano. She stressed that this would hasten the conversion of Orthodox Serbs in the Újlak (Ilok) area to Roman Catholicism.

In addition to the Dominican nuns on Nyulak Island, Erzsébet also patronized the Poor Clare sisters of Óbuda, receiving a letter of permission from two papal legates in 1472 granting her free access to their convent. Among male orders, we have records concerning her relationship with the Paulines, Carthusians, Augustinians, and Franciscans. She provided significant support for the cause of reform in the Observant Franciscan Order either by building monasteries for their benefit or transferring existing monasteries to them.

Erzsébet’s religious devotion was also evidenced by her gestures towards her heavenly patron, Saint Elizabeth of the Árpád dynasty, also known as Blessed Elizabeth the Widow. In 1465, the queen mother set the date for one of the annual fairs to be held in Újváros to coincide with Elizabeth’s saint day, November 19, and in 1477, she donated the market town of Szentetornya to the Saint Elizabeth Chapel of the Queen’s Castle in Óbuda. The deed of this donation, faithfully chronicling the event, reflected Erzsébet’s spiritual connection to her namesake patron saint: “We hope that the prayers and glorious merits of Saint Elizabeth may be a comfort to us not only on earth but also in the heavenly realm!”

The queen mother also played a role in stabilizing the political situation in the wake of the plot led by János Vitéz de Zredna, now the Archbishop of Esztergom, which broke out in 1471. The king sought to win over the wavering loyalty of Miklós Újlaki, the Ban of Macsó, who initially took part in the uprising but then betrayed it to Mátyás, by appointing him King of Bosnia in the autumn of that year. According to the charter issued by the new Bosnian king on May 7, 1472, Erzsébet had adopted him as her son, who in return swore eternal fealty to her and Mátyás.

Familial duties of the queen mother

Erzsébet Szilágyi's last major public function was connected to her son’s third – and final – royal marriage. It was she who headed the ceremonial delegation in Pettau in December 1476 that welcomed Beatrice of Aragon on her way from Naples to Hungary. The king’s mother accompanied her future daughter-in-law to Székesfehérvár, where the queen’s coronation took place, and then at the end of the month to Buda, where the royal wedding was held at the Assumption Church, naturally attended by Erzsébet herself.

Erzsébet Szilágyi became a grandmother on April 2, 1473, when Mátyás Hunyadi’s mistress Borbála Edelpeck (Barbara Edelpöck) gave birth to his only child, János Corvinus. The child was probably raised by his mother until the age of three or four, thereafter living with the king in Buda from 1470. However, when Beatrice of Aragon arrived in the Kingdom of Hungary in late 1476, Borbála was forced to leave the country, leaving her child behind in Buda. Since Queen Beatrice understandably did not want to care for her husband’s illegitimate child, the only possible “surrogate mother” for little János was his grandmother, Erzsébet Szilágyi.

Erzsébet had no meaningful say in the selection of her grandson’s tutors, just as she had no say in the case of her own sons. Nevertheless, she still presumably oversaw János’s intellectual development, given that the boy continued his studies at the court in Buda, and we know that his paternal grandmother resided in Buda almost continuously from December 1475 onwards.

Erzsébet was very fond of János Corvinus. One reason for this may have been that – according to Antonio Bonfini – the grandson bore a close resemblance to his paternal grandfather – János Hunyadi, the “Scourge of the Turks” – from whom he also received his first name. And considering that none of her royal daughters-in-law were able to give her any grandchildren of their own, Erzsébet’s only hope was that János Corvinus would continue her family line and inherit his father’s empire. As his grandmother, she naturally sought to increase János’s chances of inheriting the throne, and from 1482 onward, her grandson became the beneficiary of King Mátyás’s policy of granting estates. Adding to this, Erzsébet, who was now nearing the end of her life, also willed her estates in Debrecen and Munkács to her grandson.

Erzsébet Szilágyi de Horogszeg’s life came to an end in the latter half of June 1484. She was 73 or 74 years old. Mátyás laid his beloved mother to rest in the traditional burial place of Hungarian kings, the Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Székesfehérvár, in the funeral chapel built for his family. Prince János Corvinus undoubtedly named his only daughter Erzsébet in honor of his late grandmother. In his funeral oration for Mátyás Hunyadi, held in the city of Ragusa on May 4, 1490, a month after the Hungarian king’s death, the humanist Croatian poet Aelius Lampridius Cervinus (Ilija Crijević) remembered the king’s mother with the following words: Mater illius Elisabeth sapientissima virago ac quaedam heroica mulier fuit [His mother Elizabeth was a most wise and indeed heroic woman].

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)