Hungarian historiography prior to the regime change attached great importance to the (unsuccessful) arming of Hungarian workers during the ill-fated armistice attempt of October 15, 1944, when Hungary tried to break away from its alliance with Germany. Historical studies have generally echoed the reflections expressed in 1979 by the Hungarian trade union leader, Miklós Somogyi, who played an important role in establishing contact between the then Hungarian government and the anti-Nazi underground. According to Somogyi, Hungary’s then head of state, the regent Miklos Horthy, and his followers “were fearful of arming the working class and were in truth opposed to it because they wanted to maintain their regime.”

Although more recent scholarship has indicated that the most an armed populace could have presented would have been as an auxiliary force during Hungary’s breakaway attempt, the questions remain open whether the government purposefully refrained from embarking upon such a resolute measure in October 1944 and whether the civilian population was in fact willing to take up arms.

Plans and possibilities

The idea of arming some of the workers against the Germans and the Arrow Cross came to the fore in mid-September 1944, when the Hungarian leader Miklós Horthy began pondering the dispatch of an armistice delegation to Moscow. In his 1953 memoirs, Horthy – then living in exile – adhered to the Cold War notions of the time and distanced himself from any contact with the Hungarian resistance, that is, the communists.

“There were also a few legitimist elements who were in contact with the political underground movement, while the communists, led by László Rajk, were waiting for the Russians and retained but a nominal contact with it. The Chief of State Security Police, General Ujszászy, was chosen as contact man, for he was known to be a keen opponent of communism and thus unlikely to rouse the suspicions of the Germans. A number of discussions were held between General Ujszászy the representatives of the different groups. Among the subjects discussed was the arming of the workers to enable them to guard factories, bridges, roads, and railways. Major-General Bakay, the Commander of the Budapest Army Corps, was to supervise the distribution of arms.”

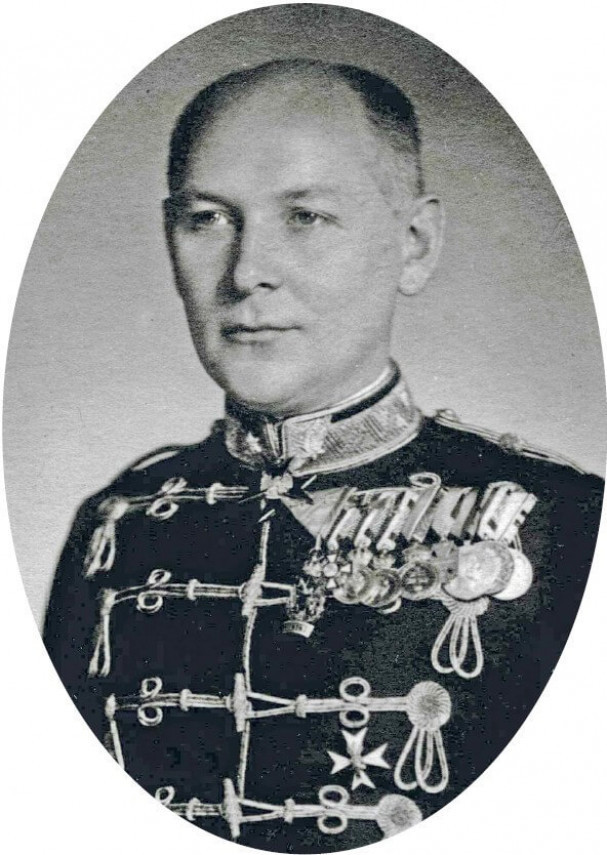

Lieutenant-General Szilárd Bakay, commander of the I. Corps in Budapest, played a key role in securing the city during the breakaway attempt. A tough soldier, he readied the defense of the capital against the Germans and their Hungarian supporters with rare determination. Bakay was abducted by the Germans in the early hours of October 8 and dispatched to the Mauthausen concentration camp.

Thus, execution of the plan was entrusted to the commander of the I. Corps in Budapest, Lieutenant General Szilárd Bakay, who had the key task of securing the city during the armistice attempt. Bakay was a tough soldier and a forceful leader who did not shy away from individual initiatives. Armed with rare determination, Bakay set about the task of preparing the capital’s defense against the Germans and their Hungarian supporters. He apportioned the city’s defenses into five sectors and three concentric circles. The innermost defensive belt encircled the castle and the city center, while the outermost encompassed what were the suburbs at that time.

In late September, Bakay toured the city garrisons, warning officers of the expected clash. At an officers’ meeting of the 2nd battalion, 9th Szeged Infantry Regiment stationed in Fót, on Budapest’s northern outskirts, he openly explained that the unit might be used to defend Horthy against the Germans and that it might even be necessary to arm some of the workers to fight alongside them. Horthy’s only surviving son, Miklós Jr., was assigned to this battalion as a reserve officer. The plan, however, was divulged to the German security services, and in the morning hours of October 8, Bakay was abducted and transported secretly to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

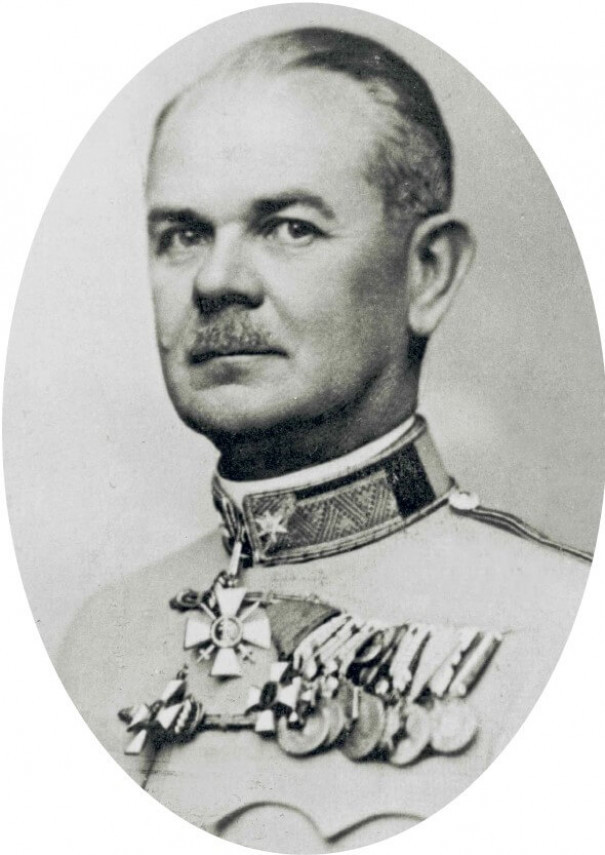

Lieutenant General Kálmán Hardy, the commander of the River Guard and a personal relative of Horthy’s, also played a role in arming local civilians. Hardy was expected to recruit the workers in the city’s Csepel district in the south in addition to his task of securing the capital’s northern and southern approaches and guarding the bridges. Hardy, who was well-known for his anti-Nazi views, was equally energetic about the plan as Bakay. On September 27, he held an officers’ meeting at the River Guard headquarters, where “he called on the officers to keep quiet, especially around the Germans. [...] He read out the chief of staff’s orders regarding officers being armed and commented that everyone should carry a firearm and that if anyone were to try to disarm them, they should feel free to open fire and that he would do the same.”

The only hitch was that we know all this from the Arrow Cross newspaper Hungarista napló [Hungarist Diary], with the informant being Hardy’s chief of staff, who arrested his own commander on the night of October 15.

Miklós Horthy Jr., known to his contemporaries as “Nicky,” headed the so-called “Breakaway Office,” which sought to forge connections with underground anti-German organizations.

In the end, the Horthy government residing in Buda Castle declined from entrusting Bakay or Hardy with the task of contacting the workers’ representatives. The latter had been provided few details about the breakaway attempt, while Bakay was burdened by his past anti-communist views and reputation as a “partisan hunter.” The task fell to Lieutenant-General Károly Lázár, commander of the Royal Life Guard and, like Hardy, a (distant) relative of the regent, and who played an important role in preventing the deportation of Budapest’s Jews in early July 1944. According to Lázár’s recollections, he had received instruction directly from the Regent’s personal office to establish “connections with the leaders of the capital’s workers.” Since the commander of the Royal Life Guard had no such connections, he began to set out feelers in various directions. The most important task was assigned to Major General István Ujszászy, the former head of the Hungarian General Staff’s Intelligence and Counterintelligence Department and the State Security Center, whom Lázár entrusted with contacting the Hungarian Front, the coalition of underground political organizations resisting the Germans, “in order to arm the workers” – the major general testified later.

Meanwhile, the head of the “Breakaway Office,” Miklos Horthy Jr., known to his contemporaries as “Nicky,” was trying to establish his own links with the anti-German underground. Shortly after the first Moscow peace delegation returned home, on October 3, 1944, the regent’s son contacted Miklós Somogyi, president of the National Hungarian Construction Workers’ Association, who had been released from internment a few weeks earlier and who was in close contact with a resistance group called the Hungarian Patriots’ Freedom Association. Somogyi informed Horthy Jr. that they could “mobilize 25-30,000 people for armed resistance in a matter of days.”

The trade union leader would revisit these discussions several times during the Kádár era, repeatedly blaming the government’s hesitancy and lack of resolve for causing the resultant breakdown in cooperation. However, he also noted that he expressed to his interlocutor that it would be best if weapons were to be deposited for them “in some designated place.” “We can organize it, you just have to come up with the weapons,” he added confidently. Somogyi even engaged in discussions with the regent himself but was forced to admit that he had no authority to negotiate arming the workers.

Negotiations

The Hungarian Front’s discussions with the government are much better known than those recounted by Somogyi. The Hungarian Front was established in mid-May 1944 with the participation of the Social Democratic Party, the Independent Smallholders’ Party, the legitimist Dual Cross Alliance, and the Communist Party – then called the Peace Party. In the summer, the Hungarian Front expanded further with the inclusion of the Catholic Social People’s Movement, which had been created a year earlier. By the end of September, the umbrella organization was strengthened further through the aegis of the National Peasant Party and its representative, Imre Kovács. By this time, the Hungarian Front – chaired by Árpád Szakasits – already had a steering committee set up in the apartment of the retired former chief magistrate of Veszprém County, Pongrác Kennesy, located at 21 Ilona Street in Budapest’s castle district.

The chief of staff of the Hungarian Army, Colonel General János Vörös, losing faith in a German victory, also sought contact with the underground coalition of resistance organizations, eventually meeting twice with Árpád Szakasits and Zoltán Tildy at the resistance headquarters on Ilona Street in the first days of October. Vörös expressed interest in arming five thousand civilians, but no agreement was reached here either. The chief of the Hungarian general staff stated that “he would need at least three weeks before he could take appropriate military measures to ensure success of the armistice effort” – recalled Szakasits in 1945.

It should be noted that when these discussions were taking place with János Vörös, the Hungarian Front had already drafted a second, strongly worded memorandum. Drafted by László Rajk, secretary of the underground Communist Party Central Committee, the document stated, “

We do not attach any conditions to the most active participation in the fight against the German occupiers. If the country’s leaders undertake the fight, they can count on our full support even without prior agreement and organizational ties.”

Rajk had quickly found himself a participant in the discussions. Contact with Rajk, who had been released from the Margit Boulevard prison on September 10, 1944, under unclear circumstances, was made indirectly along the Lázár-Ujszászy line. As an initial step, István Ujszászy, one of the most informed leaders of Hungarian counterintelligence and intelligence during World War II, had contacted Imre Kovács, a member of the Peasant Party, about the arming of civilians – rather than contacting those politicians connected to the labor movement. Through the intercession of his paramour, the actress Katalin Karády, Ujszászy was able to meet Kovács towards the end of September 1944, when the latter was also holding tentative discussions with Miklós Horthy Jr. Ujszászy also wanted to discuss military issues with Kovács, but the latter rejected this, saying that he would bring “someone from the communists, as it would make it more interesting.”

The Ujszászy-Rajk-Kovács meeting thence took place in a villa in Buda’s Hűvösvölgy neighborhood. According to Kovács, Rajk already expressed the view here that “we will have to wait and see what happens with the memorandum; only then can we go into the details. There are political preconditions to armed action, and we can’t discuss matters seriously until we’ve clarified the situation.” In the end, the former head of Hungarian intelligence and counterintelligence and the Communist Party secretary discussed Hungarian history over drinks and addressed each other in familiar terms. No conclusive decisions were taken, either politically or militarily.

The most important discussions, however, took place between Imre Kovács and Károly Lázár at the Royal Palace. This clandestine meeting most likely took place on the morning of October 8, 1944, a few hours after General Bakay’s abduction. The details of the meeting are best expressed by citing the transcript of an interview conducted with Kovács in 1978:

“We entered a [...] large study, and there was Lieutenant-General Lázár of the Guard, holding himself rather stiffly, a map laid out on a large table in front of him […] He said, ‘Here is the inner line of defense, and there is the outer line of defense. We want to block a potential German attack here; we need your help.’ [...] I was stunned. What’s this all about? Well, it was exactly what we had proposed in our memorandum, that the workers should be armed and a national guard, workers’ guards, should be formed. Lieutenant-General Lázár proposed that 10-15 thousand workers be equipped with light weapons: handguns, light machine guns, hand grenades, revolvers, everything. He asked me, whether I could come and get the weapons’ I told him, ‘No.’ (I was quite surprised by all this!) […] And he added, a bit pretentiously, ‘Because if you can’t take them, I can have them transported to wherever you want.’ ‘Well,’ I told him, ‘we can discuss this as well.’ And he then said, ‘I can have them placed in the rock cellar of the Kőbánya Brewery.’ […] and we decided I would discuss this with the communists.”

In other words, although Lázár was described as being very direct and would have acted in direct compliance with the Hungarian Front’s memorandum, the front’s delegate nevertheless couldn’t hide his surprise and at the end of much discussion concluded that they were unable to take the weapons. Lázár, however, even entertained Somogyi’s suggestion of moving the cache of weapons to a neutral location.

Kovács Imre’s reluctance was understandable, as he had no control over masses, not being a trade union leader. It must have been (or should have been) obvious to those at the time that this was the only realistic way to mobilize thousands of reliable citizens against the Germans and the Arrow Cross. Kovács, however, did not convey Lieutenant-General Lázár’s offer to the trade unions or even to the Hungarian Front; rather, he took it to the Communist Party, which did not enjoy mass support and which was not engaged in the common anti-German struggle at that time, being preoccupied in blowing up the statue of former Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös in Buda’s Tabán district instead.

We can ascertain the reasons for this from Imre Kovács’s 1948 German-language book Im Schatten der Sowjets [In the Shadow of the Soviets]. In it, the National Peasant Party politician now living in exile, after having fled the Communists in the fall of 1947, assessed his discussions with Lázár as follows: “[The Hungarian Front] had not contemplated taking military action up to that moment [...] All our calculations had been built around the regent, and what had seemed impossible previously had now become a reality: the country, along with Horthy and the army, was ready to break with the Germans and end the war on the side of the Western Allies. The Communists had always claimed that they alone could mobilize the masses – and that is why I had to discuss the matter with them.”

Although Kovács mentioned “Western Allies” in his Swiss-published book, the reality was that it was in Moscow that the official Hungarian delegation was negotiating an preliminary armistice and it was the Red Army that was advancing through the country’s territory.

The Peasant Party politician immediately rushed from Castle Hill with the big news of Lázár’s proposal. They were in trouble. “The problem I felt was where we’d find 10-15 thousand workers that we could arm,” Kovács pointed out in a 1978 interview. Rajk discussed the situation with his comrades and they decided to accept Lázár’s offer. We do not know what they based their decision on as there is no evidence that anyone could have mobilized thousands of workers at that time. The absence of armed workers did not occasion any shame or embarassment, however. According to Kovács, Ujszászy informed his interlocutors the next day that “His Excellency [Horthy] had withdrawn Lázár’s mandate.” This was most likely due to Bakay’s abduction.

Contingency plans

The abduction of Szilárd Bakay fundamentally shattered the military security of the breakaway attempt in the capital since Bakay’s successor at the head of the I. Corps in Budapest, Lieutenant-General Béla Aggteleky, had not been informed about the breakaway plans, whereas the Germans now had up-to-date information about military measures planned against them both in Budapest and in the surrounding area.

According to Lázár’s own account, it was only after the Rajk–Kovács line had failed that he contacted the social democrats Lajos Kabók and Sándor Karácsony, who were later murdered by the Arrow Cross. In other words, it was only after this initial failure that Lázár pursued contact with those trade union leaders whose reputations made it advisable to discuss matters with them at the time due to their personal standing and authority. In his memoirs, the lieutenant-general of the Guard only made mention that he had received the two trade union leaders at his apartment, but other sources suggest a more serious connection. As Iván Fráter, a member of the Szent-Györgyi resistance group (established by Hungarian biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi) recalled: “It was through former MP Lajos Kabók that approximately 20,000 militarily trained and organized iron and metal workers also offered to participate in open resistance.

[Gyula] Ambrózy, head of the Cabinet Office, whom Lázár introduced me to personally, was reluctant to present our plan to the regent.”

Lieutenant-General Béla Aggteleky, Szilárd Bakay’s successor as head of the I. Corps in Budapest, was not informed about the breakaway plans

Fráter was undoubtedly exaggerating, but we know for a fact that Szent-Györgyi’s organization, which had close ties to Lázár, did indeed have an arms depot and training base in Budapest located in the basement of the Taurus Metalworks at 37-39 Nagymező Street. This base was liquidated during the Arrow Cross takeover, and its occupants arrested and their weapons confiscated. Many people disappeared or were deported to the Dachau concentration camp by the Germans, while others were sentenced to lengthy prison terms by the Hungarian authorities.

In addition to the left-wing labor leaders, Károly Lázár had another option in store, about which he himself wrote rather succinctly after the war: “I had a number of discussions with a representative of the Jewish Council who came to my office regarding the issue of forced laborers.” Samu Stern, the head of the Central Jewish Council, confirmed and clarified this cooperation in his memoirs: “The various militant strands of the resistance movement were brought together in the hands of the lieutenant-general of the Guard, and we negotiated with him to include the labor battalions serving in Budapest in the armed resistance. We forwarded him a list of labor companies in Budapest along with their locations with the intention of receiving instructions regarding which company should march to which barracks when the time came to arm them.”

These labor companies may have been the forced labor formations mentioned by Lázár. According to Stern, these units had originally been created to employ those who had been forcibly relocated to the “yellow-star houses” as compulsory residences for Budapest’s Jews. The arming of the labor companies, which were challenging to assemble, was to have commenced on October 16; thus, the timing of the breakaway attempt likewise thwarted these plans.

The most well-known meeting between the resistance and the government, that is, when Árpád Szakasits and Zoltán Tildy visited the regent in Buda Castle, took place on October 11 – the day the preliminary armistice was signed in Moscow. Whereas Mikós Horthy, with laconic brevity, summed up the meeting, saying “it did not yield any results,” it was the regent’s never-ending rhetoric that stuck with Tildy. Szakasits recalled in the spring of 1945 that “the regent informed us that the armistice talks or at least the attempts to do so, had reached an advanced stage and that within the week, or perhaps sooner, his decision to seek an armistice with Soviet Russia and the Allies would be made public.” The regent also promised the release of political prisoners, the future formation of a coalition government, and the arming of “reliable labor.”

On October 13, the regent also held discussions with representatives of the Hungarian Patriots’ Freedom Association, among others, on arming the workers. The breakaway attempt was also set for October 18. It was also on October 13 that the chief of staff of the Hungarian Army, Colonel General János Vörös, met with Rezső Hadácsy, a retired colonel who had previously assisted him in illegal contacts, and asked him if he would take “command of a unit of workers.” Hadácsy readily agreed and immediately inquired about the necessary weapons. Vörös promised to take immediate action; however, in light of his behavior on October 15, when he signed an order announced over the radio contradicting the regent’s proclamation, the sincerity of his intentions should be viewed with skepticism.

Even the supporters of the planned change in course were taken aback by the regent’s decision to announce the proclamation on the following day – Sunday, October 14. Even a well-prepared resistance network with a clear chain of command would probably not have reacted well to this unexpected – and unplanned – decision at the governmental level. According to the post-war communist narrative, the Communist Party had placed its organizations on “permanent standby” for October 15 and the days leading up to it while waiting for the guns to arrive.

According to Piroska Döme, a prominent figure in the miners’ resistance, “this meant that the liaisons for the organizations met every four hours for days on end. The purpose was to ensure that weapons Horthy had promised could be delivered to the factories and combat groups.” However, the still relatively unorganized combat groups consisting of little more than two dozen youth were hardly a major element for the success of the breakout. As for the factories, it is worth referring to László Rajk's partner, Júlia Földi, who spoke on this subject in an interview in 1980, stating that “the Communist Party was quite weak in the factories although the Demény-faction [a Communist party splinter group] was strong in the larger enterprises.” Thus Földi, who was not a member of the Demény faction, pointed to yet another unexplored dynamic.

Conclusion

Lieutenant-General Károly Lázár of the Guard acted in accordance with Lieutenant-General Szilárd Bakay’s intention of arming civilians and there is no doubt that both high-ranking military officers were serious about arming 10-15,000 “reliable” members of Budapest’s civilian population in order to secure the breakaway attempt. This would not have been a negligible force, considering that recent research has disclosed that there were roughly 35,000 armed Hungarians facing approximately 27,000 Germans in and around Budapest on October 15, 1944.

Lieutenant General Károly Lázár, commander of the Royal Life Guard, in whose hands the various strands of the resistance movement came together

Part of the problem regarding the planned workers’ militias was the inappropriate selection of contact people, as neither Miklós Somogyi, who was approached by Miklós Horthy Jr., nor Imre Kovács, who was “introduced” to Lázár by Major General István Ujszászy, proved suitable for the task of organizing the arming of the workers. Lázár was supposed to provide the cache of weapons to be handed over and was to take into account requests made in this regard during discussions with Miklós Horthy Jr.

The abduction of Lieutenant-General Szilárd Bakay stymied all further serious planning, although it is doubtful the resistance organizations would have succeeded in mobilizing thousands of workers in any case. If we hadn’t backed out, “we would have seriously compromised ourselves,” Kovács said in a posthumously published article. The chronic indecision characterizing the Horthy government’s breakaway plans following Bakay’s abduction was noticable in other areas as well. The aged and exhausted regent began to visibly panic.

A contributing factor in the failure of the collaborative effort was the fact that the Horthy government had no established links with organized social-democratic labor, even though most of the trade union leaders continued to reside legally even during the German occupation. Naturally, we cannot know what Lajos Kabók or Sandor Karácsony would or could have done had they not been sought out at the last minute. Both men enjoyed some authority over at least that portion of the organized masses that could be assumed were ready to fight against the Germans and the Arrow Cross.

However, besides the decades-long mutual distrust between the Horthy-era political elite and the left-wing labor leaders, there was an additional, less talked about aspect that weighed heavily on the decision makers. By the fall of 1944, it was not at all clear to what degree the workers could be relied upon, since the far right had been endeavoring for decades – and not without some success, as the 1939 parliamentary elections revealed – to draw the workers away from the Social Democratic Party and the trade unions.

(translated by John Puckett and Andrea Thürmer)